PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS

See something of interest? Complete a publication request to order a digital or hard copy.

Farming on a Loop

by Jake BuehlerIn Hawaiʻi and the Pacific, physical space for agriculture is substantially more limited than on continental landmasses. This has made farming practices that combine efficiency with a low impact on land and water use especially useful for producing food in the Pacific region. Now, one food production system is increasingly recognized here, and across the world, for its capacity to reduce waste and cost while still producing high yields: aquaponics. Aquaponics is farming on a loop. Fundamentally, the process is a merger of aquaculture—where fish or shellfish are raised in tanks or ponds—and hydroponics, where plants are grown

Reviving Cultural Practices and Restoring Self: Rosalyn Concepcion

by Stacy KishThe 400-year old stone walls of Waikalua Loko Iʻa, a Hawaiian fishpond in Kāneʻohe, Oʻahu, retain a history that has almost been lost to disrepair during the past century. Rosalyn (Roz) Concepcion has been working to restore the fishpond and bring its gifts of food sovereignty, cultural restoration, and environmental healing back to the community. “When I stepped in, I wanted to understand the historical practices of the fishpond,” said Concepcion, the kiaʻi loko iʻa, alaka`i, or fishpond manager. “By bringing back old practices, we are bringing life back into the pond.” Concepcion’s role as the kiaʻi loko

Farming the Open Ocean—Is Offshore Aquaculture in Hawaiʻi the Future of Seafood?

by Josh McDanielOn the island of Hawai‘i, about a half mile off Keāhole Point near Kona, nine large net pens teem with hundreds of thousands of kanpachi (Seriola rivoliana, or longfin amberjack). Blue Ocean Mariculture’s kanpachi fish farm is the only commercial open-ocean aquaculture operation in the United States, and it may be a model for an industry that many believe is primed for growth. “We have the expertise, the technology, and the entrepreneurs who are ready,” says Kat Montgomery, the seafood, aquaculture, and ocean policy director for ESP Advisors in Washington D.C. “In the next 10 years, I believe

Propagating resilience

by Natasha VizcarraIt was a warm, cloudy Saturday at Maunalua Bay Beach Park. Under a blue tent, masked volunteers at the Mālama Maunalua Hana Pūko‘a event bent over water saws to gingerly cut coral into large thumb-sized pieces. Under a green tent, more volunteers stood around waist-high tanks and glued coral fragments—branch side upwards—to aragonite plugs. These were not ordinary bits of coral. Stress tests at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology’s (HIMB) Coral Resilience Lab, which continues the legacy of renowned scientist Dr. Ruth Gates, showed they were more heat resistant with a better chance at surviving current and

Sharing the Catch

by Robin DonovanIf you read the news, it’s everywhere: rising sea levels, warming oceans, degraded coastlines, and dying coral reefs. The consequences of climate change are apparent around the globe, but for fish-loving island communities like those in American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Marianas, the urgency of balancing sustainable practices with growing demand for fish, both for subsistence and for profit, is leading to creative partnerships that blend knowledge gained from western research and local fishing practices. Guam Guam has felt fish shortages more acutely than some of its neighbors due to its larger population size and smaller reef

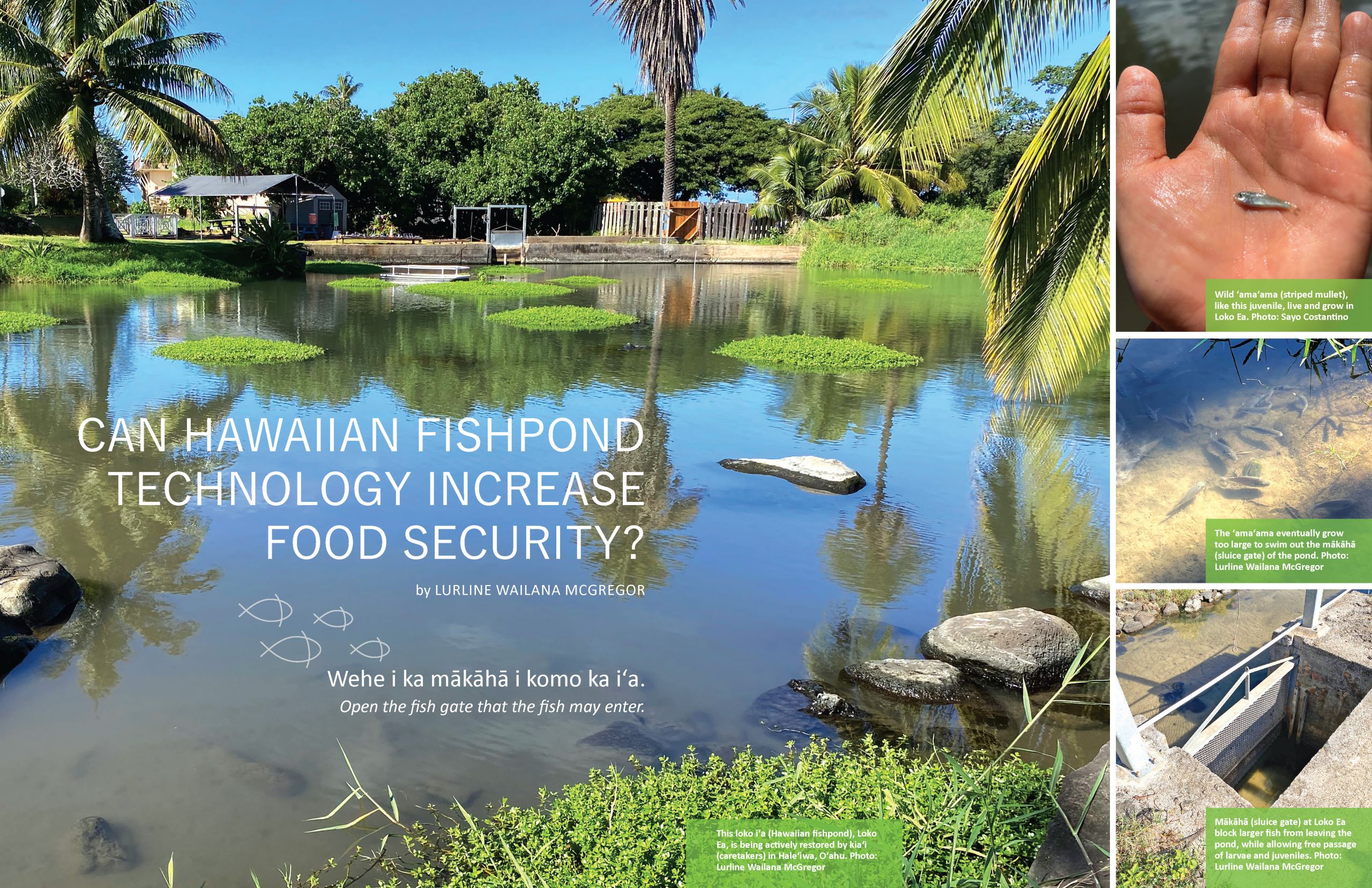

Can Hawaiian Fishpond Technology Increase Food Security?

by Lurline Wailana McGregor“Wehe i ka mākāhā i komo ka iʻa,” open the fish gate that the fish may enter, is an ʻōlelo noʻeau (Hawaiian proverb) referencing a strategy used to trap fish in the loko iʻa, as well as a trap for invading warriors. For over one thousand years, all it took to attract pua (juvenile fish) into the approximately 488 fishponds that Native Hawaiians built along the shores of the islands, was to open the gate, due to its innovative construction. These loko iʻa were abundant with many species of fish, including the revered ʻamaʻama (striped mullet) that

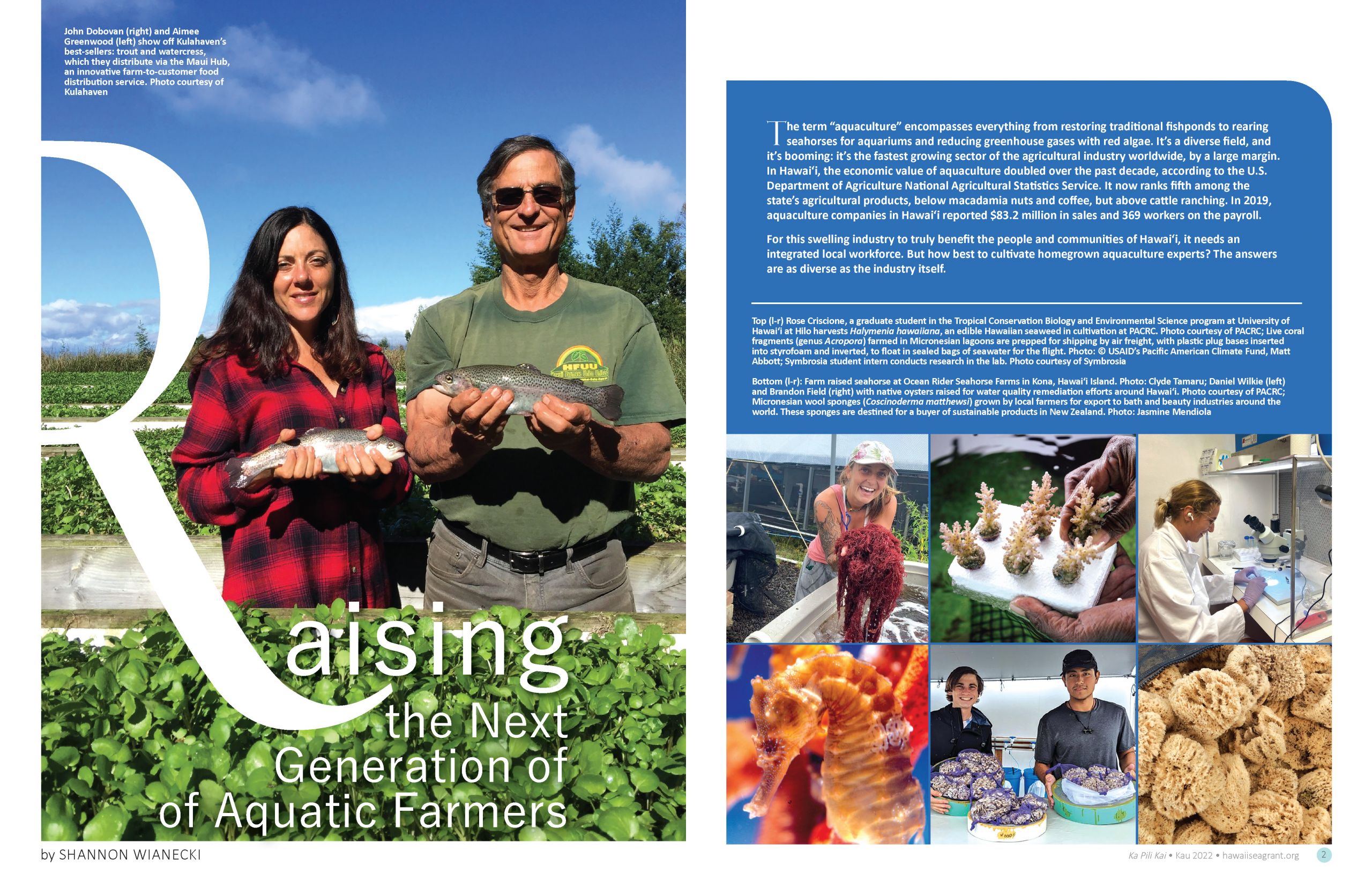

Raising the Next Generation of Aquatic Farmers

by Shannon WianeckiThe term “aquaculture” encompasses everything from restoring traditional fishponds to rearing seahorses for aquariums and reducing greenhouse gases with red algae. It’s a diverse field, and it’s booming: it’s the fastest growing sector of the agricultural industry worldwide, by a large margin. In Hawai‘i, the economic value of aquaculture doubled over the past decade, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. It now ranks fifth among the state’s agricultural products, below macadamia nuts and coffee, but above cattle ranching. In 2019, aquaculture companies in Hawai‘i reported $83.2 million in sales and 369 workers on

The Limu Eater – A Cookbook of Hawaiian Seaweed

Vintage Reprint Available in October 2022 This reprint of The Limu Eater is the product of a partnership between Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA) and the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program (Hawai‘i Sea Grant), who worked collaboratively to support the conceptualization, design, and actualization of the reprint. Support for printing was provided by the Center for Oral History at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority, and Hawai‘i Sea Grant. Partnering Organizations Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA) means “grassroots growing through shared responsibility.” KUA is a movement-building non-profit organization that works to empower communities across Hawaiʻi to

The Three ‘Io Brothers and The Rising Tide

by Keri Kodama On a bright summer day on the Island of Hawai‘i, the three ‘Io brothers packed their bags and got ready to leave for a well-earned vacation. They were on their way to visit their old friend ‘Apapane who lived by the ocean in Kapoho, and they were all very excited for it had been many years since they could visit. “I can’t wait to go swimming!” said the first ‘Io brother, the most playful of the three. “I hope the waves are good,” said the second ‘Io brother, who was the coolest. “I remember there were many

ʻAha ʻIke Pāpālua – 2020 Report

In January 2020, we came together in a visioning ʻAha - to assemble around the questions of who, what, and why our Sea Grant Center of Excellence should focus its time, energy, and efforts. In this period of change, the Center made significant progress building out existing projects and as we have grown and assumed new kuleana, we felt it appropriate that our new name, Ulana ʻIke, reflect our evolving roles and function. The ʻAha ʻIke Pāpālua Report reflects our collective aspirations directed by community partner manaʻo and advice. The report includes: An explanation of the intentionality and meaning behind

Hawaiʻi Dune Restoration Manual

The Hawaiʻi Dune Restoration Manual was written and created by the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program (Hawaiʻi Sea Grant). Hawaiʻi Sea Grant supports and conducts innovative research, education, and extension services toward the improved understanding and stewardship of coastal and marine resources nationwide. The Hawaiʻi Dune Restoration Manual is written in response to increasing awareness of the importance of preserving, restoring, and maintaining coastal dunes. There are clear ongoing impacts associated with climate change, including sea-level rise, coastal flooding, and more frequent and severe storm events, all causing beach and dune erosion. However, there are also direct human

University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program Biennial Report (2018-2019)

The University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program (Hawaiʻi Sea Grant) is organized into Centers of Excellence, a unique structure within the 34 university-based Sea Grant programs across the network. This allows the work of our faculty and staff to engage across our universities to bring multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary approaches and solutions in service to communities throughout the region. The cover images depict the passion, commitment, and diversity of people and projects that are genuinely representative of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant and our expansive focus areas. Our program’s service is truly region-wide, with responsibilities spanning a geographic area greater than

Energy Targets and Efficiency Measures in Multifamily Subtropical Buildings

The Technology | Architecture + Design journal article by associate professor Wendy Meguro and Elliot Glassman from WSP, "Evaluating Energy Targets and Efficiency Measures in Multifamily Subtropical Buildings through Automated Simulation" (April 2021) is available free online here This study demonstrates a replicable process using early design phase energy modeling to reduce energy use in multifamily residential buildings in subtropical climates and achieve net-zero site energy. Why was the study initiated? Buildings produced almost 40% of annual global GHG emissions in 2018, so reducing energy use in buildings is key to meeting climate change mitigation targets. Who is the audience?

From Loss to Recovery to Resilience

by Lurline Wailana McGregorIn 2018, Hurricane Walaka circumvented the Hawaiian Islands before circling back to pass directly over Kānemilohaʻi, also known as the French Frigate Shoals, an atoll 550 miles northwest of Honolulu. It washed away East Island, an 11-acre islet in the Lalo group, destroying one of the primary nesting and birthing spots for Hawaiian green sea turtles and Hawaiian monk seals, respectively; the Hawaiian monk seal is one of the most endangered seal species in the world. Not only did this Category 4 storm severely damage terrain, it obliterated the pristine Rapture Reef that lies about 24 meters

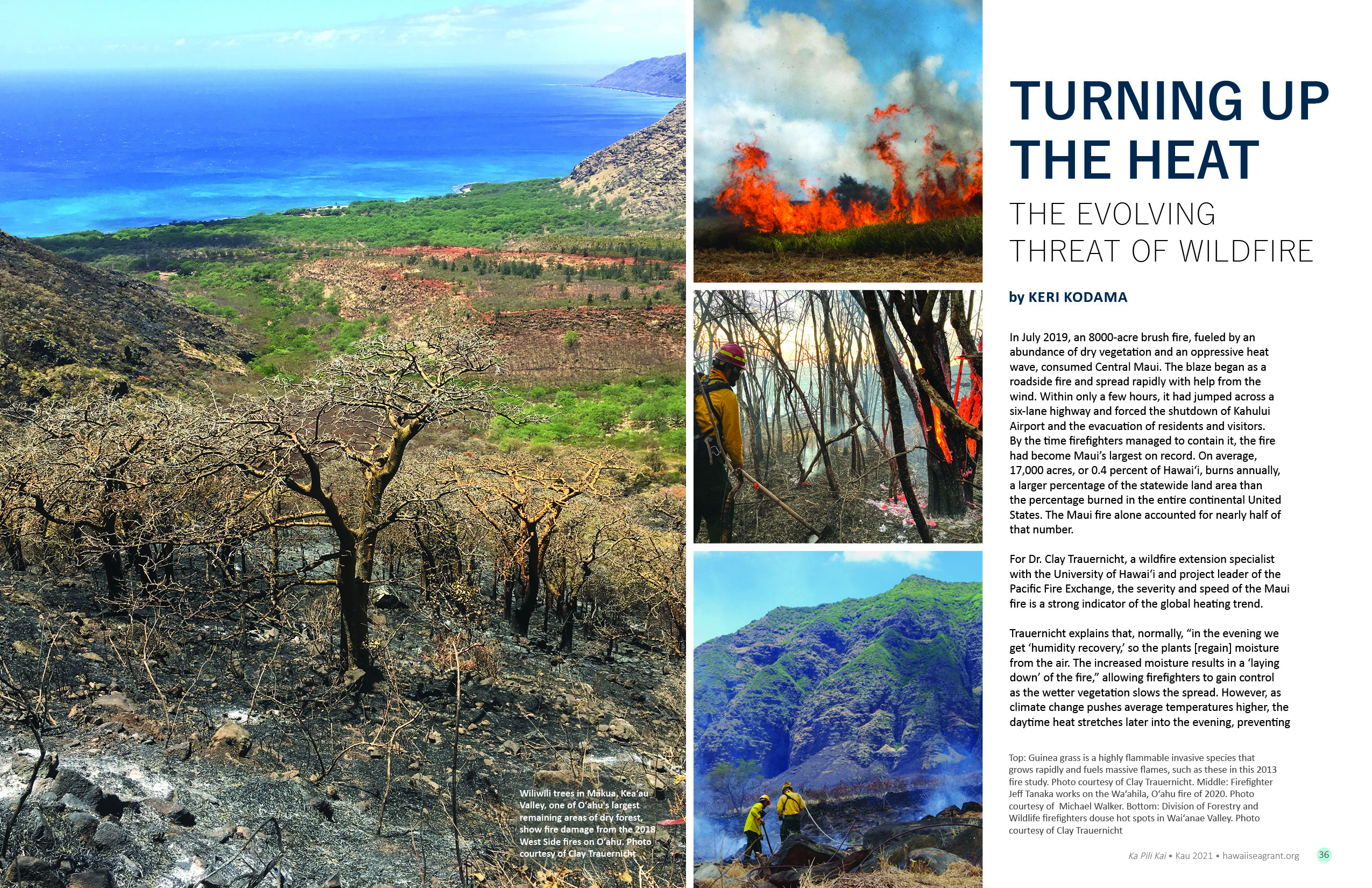

Turning up the Heat: the evolving threat of wildfire

by Keri KodamaIn July 2019, an 8000-acre brush fire, fueled by an abundance of dry vegetation and an oppressive heat wave, consumed Central Maui. The blaze began as a roadside fire and spread rapidly with help from the wind. Within only a few hours, it had jumped across a six-lane highway and forced the shutdown of Kahului Airport and the evacuation of residents and visitors. By the time firefighters managed to contain it, the fire had become Maui’s largest on record. On average, 17,000 acres, or 0.4 percent of Hawaiʻi, burns annually, a larger percentage of the statewide land area

Climigration: A look to the future for environmental migrants

by Amanda MillinNearly three decades ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicated that “the gravest effects of climate change may be those on human migration.” Estimates differ widely, but most experts agree that upwards of 25 million people will be forced to leave their homes by 2050. Yet, international and domestic laws around the world continue to take a cautious and nuanced approach to the problem. Confusion and a lack of global consensus surround even what to call these displaced persons. Nor is there agreement on where they are going, what causes their movement, and how these future

The Ocean is Feeling the Heat

by Lonny LippsettA fever is rising in the ocean. Our rampant burning of fossil fuels has produced a heat-trapping blanket of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere that has warmed the Earth. But the situation would be much worse without the ocean, which has absorbed more than 90 percent of that excess heat. Scientists reported that in 2020, the ocean held the most heat ever recorded. In recent decades (1987-2019), ocean warming has increased by 450 percent, compared to the three decades before that (1955-1986). Last year, the ocean absorbed more than 200 times as much heat as it did

Turning Down the Temperature on Urban Heat Islands

by Josh McDanielAugust 31, 2019, tied the record for the hottest temperature ever recorded at the Honolulu airport. On the same day, volunteers and city workers placed sensors on their vehicles and drove through O‘ahu neighborhoods throughout the day. Staff from the City and County of Honolulu (City) Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency (Resilience Office) used the resulting measurements to construct a detailed heat map of the island. Though it is no surprise that many hotspots were in the concrete jungle of Honolulu’s urban core, certain other windward and leeward locations also registered extreme heat indices, which was

Q & A with Matthew Gonser

by Cindy Knapman and Kanesa SeraphinMatthew Gonser, former extension faculty with the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program, was recently appointed as the chief resilience officer and executive director of the City and County of Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency. He took the time to share his thoughts and vision for the office, and how it is fostering connectivity and collaboration to turn community visions into action. Can you tell me about the City and County of Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency, and how it came about? The office was created by the

Harnessing the Elements by 2045

by Natasha VizcarraHawai‘i Senator Glenn Wakai was in a Zoom meeting in late January when he noted a kink in the islands’ renewable energy plans. The state’s only coal-fired power station was shutting down in September 2022. However, solar power projects replacing the plant’s 180-megawatt generation were delayed six months to a year. The Hawaiian Electric Company (HECO) somehow needed to source enough renewable energy to feed the grid. The whole process would include time-consuming requests for proposals, sorting bids, picking winning contractors, requesting permits, procurement, building, and testing. And they had to do it in less than two years,

RMI Homeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for Natural Hazards

Introduction When a natural hazard occurs - whether it be a tropical cyclone, tsunami, extratropical storm, king tide, flood, sea-level rise, erosion, or drought - the results can be devastating for your land, your home, your family, and your possessions. Financial losses can be particularly high in the two administrative centers of the northern and southern Marshall Islands - Majuro and Ebeye, Kwajalein - which have seen explosive growth in both population and land area since the mid-1940s. This has been especially true in Majuro, where a number of lagoonal openings along Majuro Atoll were connected by the US Navy

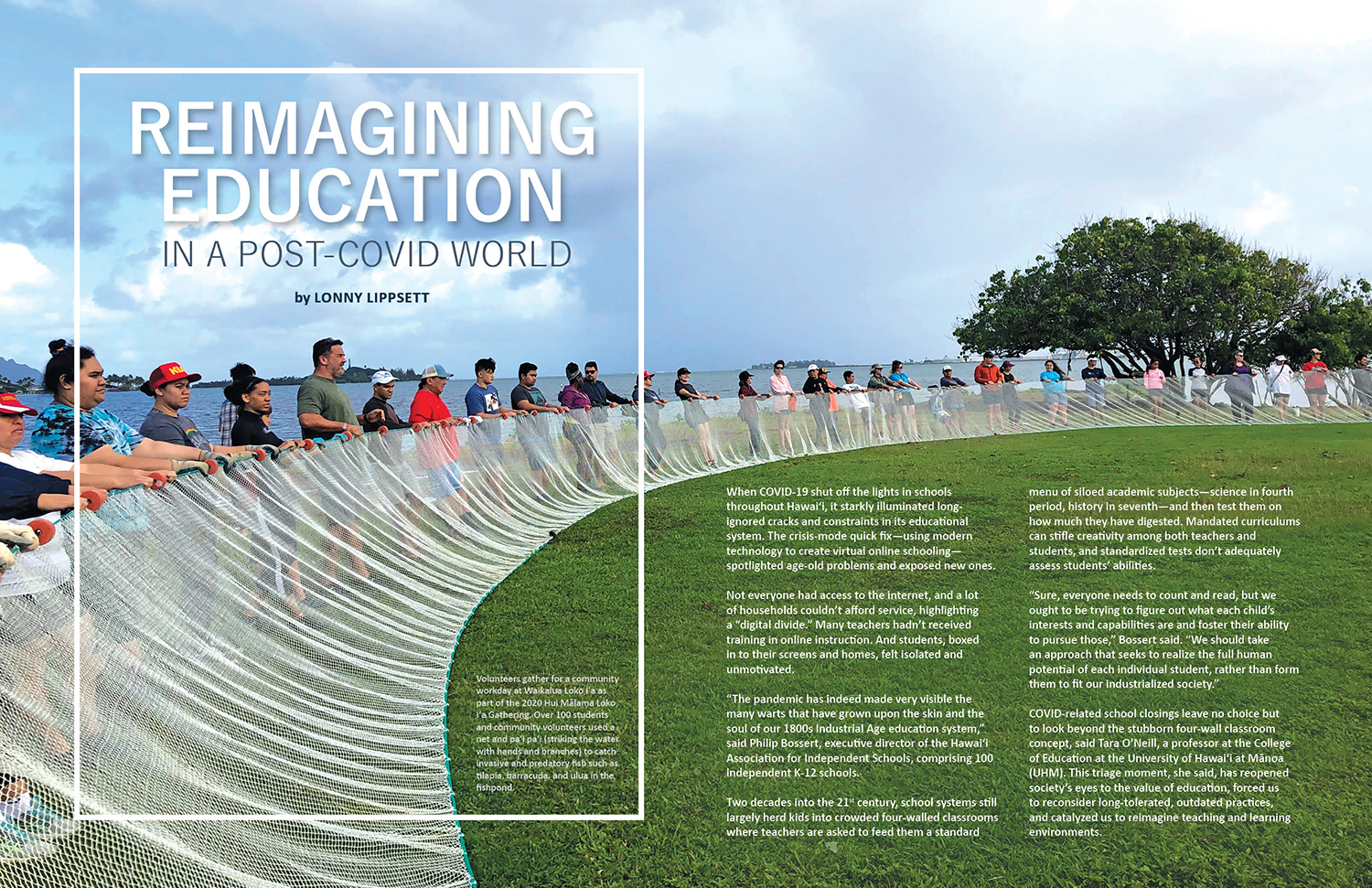

Reimagining Education in a Post-COVID World

by Lonny LippsettWhen COVID-19 shut off the lights in schools throughout Hawai‘i, it starkly illuminated long-ignored cracks and constraints in its educational system. The crisis-mode quick fix—using modern technology to create virtual online schooling—spotlighted age-old problems and exposed new ones. Not everyone had access to the internet, and a lot of households couldn’t afford service, highlighting a “digital divide.” Many teachers hadn’t received training in online instruction. And students, boxed in to their screens and homes, felt isolated and unmotivated. “The pandemic has indeed made very visible the many warts that have grown upon the skin and the soul of

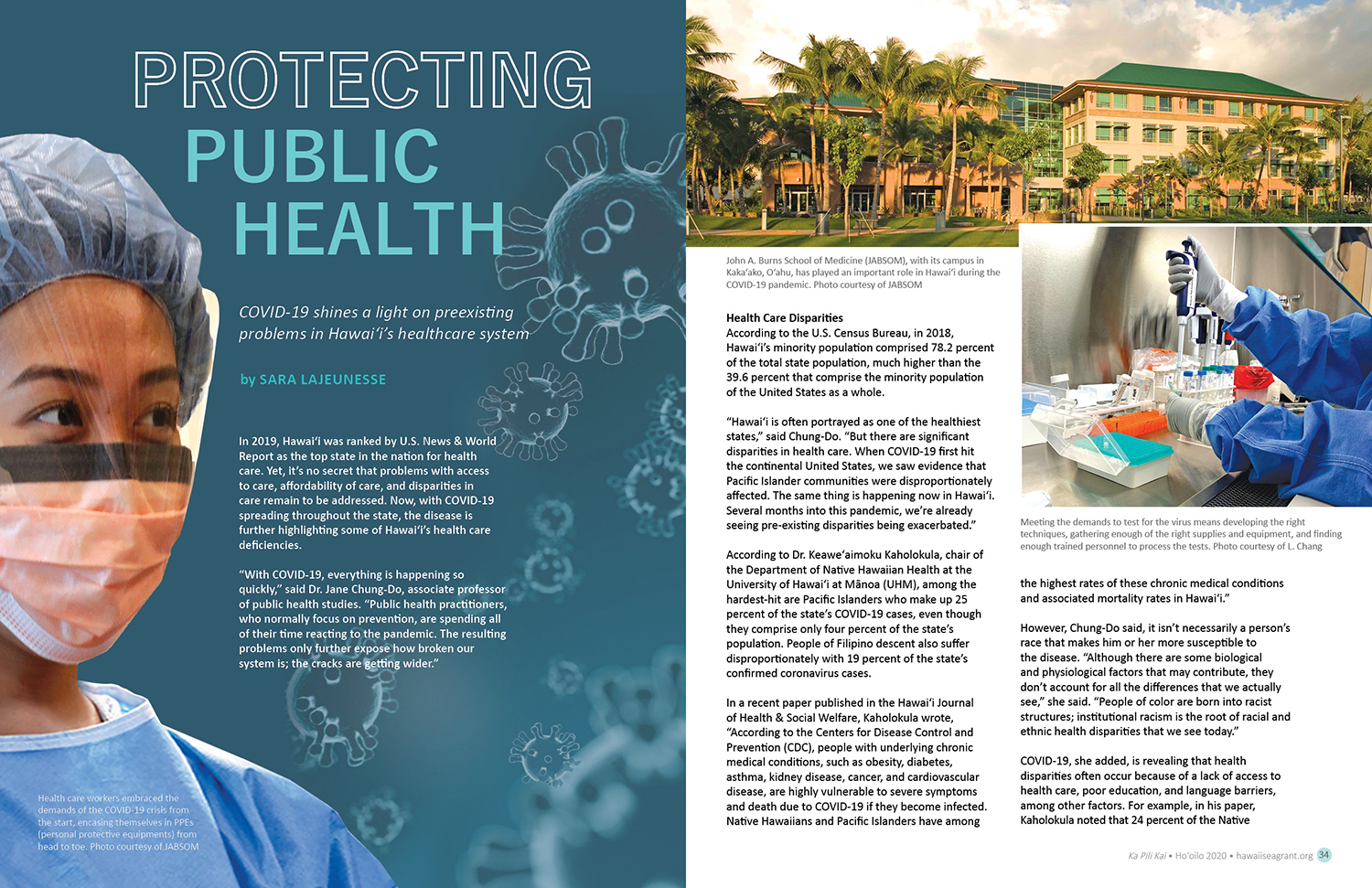

Protecting Public Health

by Sara LaJeunesseIn 2019, Hawai‘i was ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the top state in the nation for health care. Yet, it’s no secret that problems with access to care, affordability of care, and disparities in care remain to be addressed. Now, with COVID-19 spreading throughout the state, the disease is further highlighting some of Hawai‘i’s health care deficiencies. “With COVID-19, everything is happening so quickly,” said Dr. Jane Chung-Do, associate professor of public health studies. “Public health practitioners, who normally focus on prevention, are spending all of their time reacting to the pandemic. The resulting problems

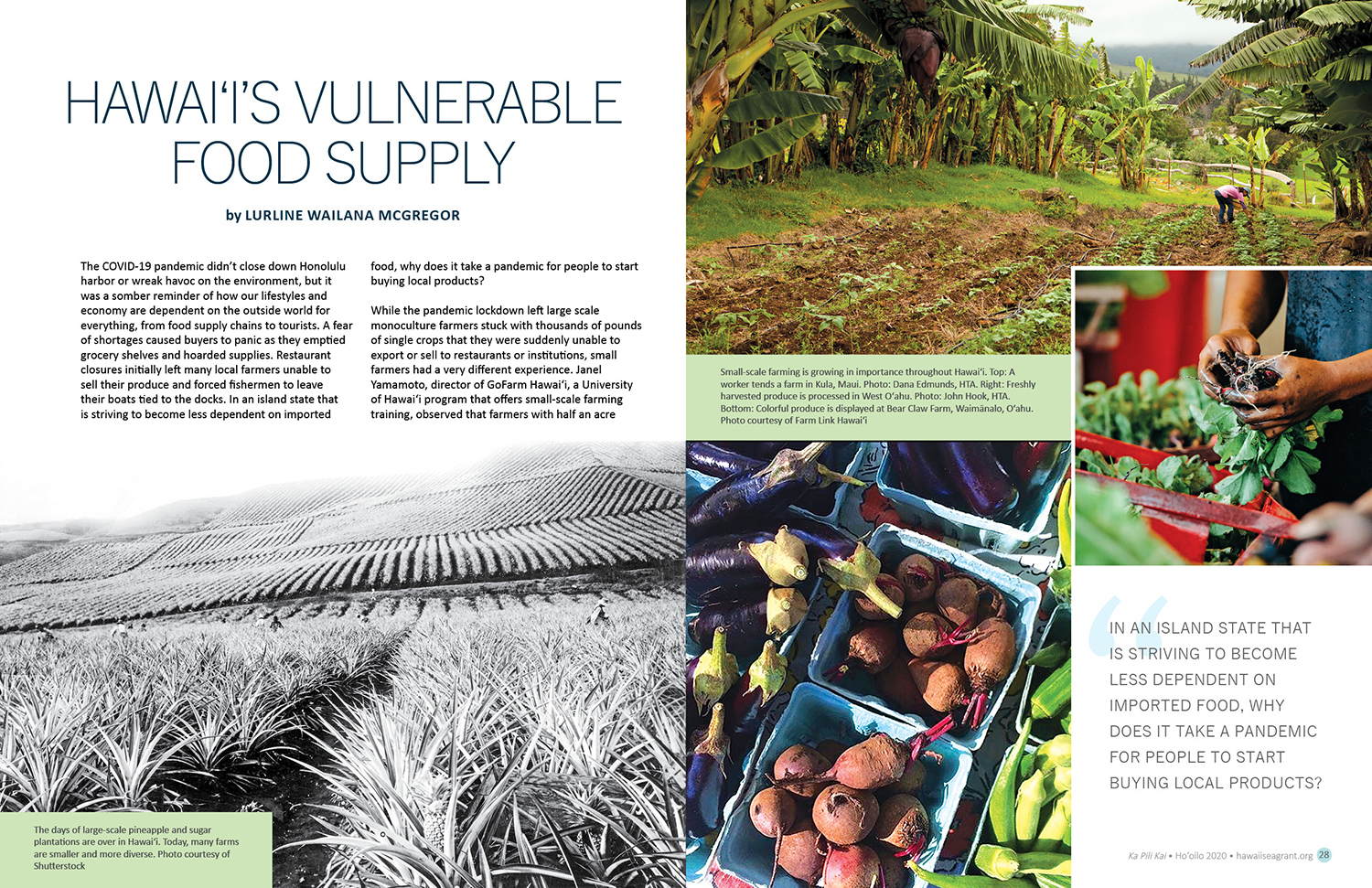

Hawaiʻi’s Vulnerable Food Supply

by Lurline Wailana McGregorThe COVID-19 pandemic didn’t close down Honolulu harbor or wreak havoc on the environment, but it was a somber reminder of how our lifestyles and economy are dependent on the outside world for everything, from food supply chains to tourists. A fear of shortages caused buyers to panic as they emptied grocery shelves and hoarded supplies. Restaurant closures initially left many local farmers unable to sell their produce and forced fishermen to leave their boats tied to the docks. In an island state that is striving to become less dependent on imported food, why does it take

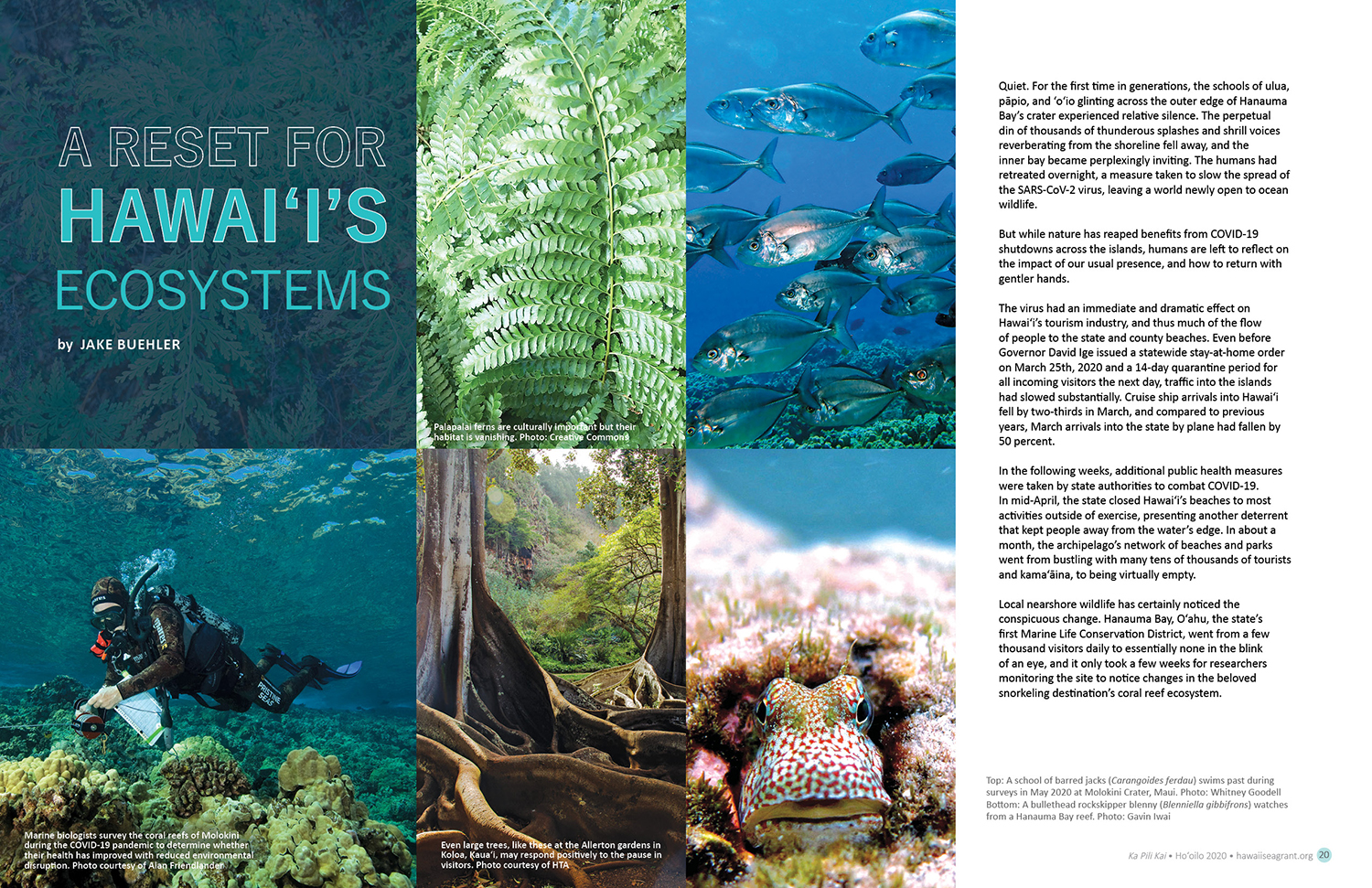

A Reset for Hawai‘i’s Ecosystems

by Jake BuehlerQuiet. For the first time in generations, the schools of ulua, pāpio, and ‘o‘io glinting across the outer edge of Hanauma Bay’s crater experienced relative silence. The perpetual din of thousands of thunderous splashes and shrill voices reverberating from the shoreline fell away, and the inner bay became perplexingly inviting. The humans had retreated overnight, a measure taken to slow the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leaving a world newly open to ocean wildlife. But while nature has reaped benefits from COVID-19 shutdowns across the islands, humans are left to reflect on the impact of our usual presence,

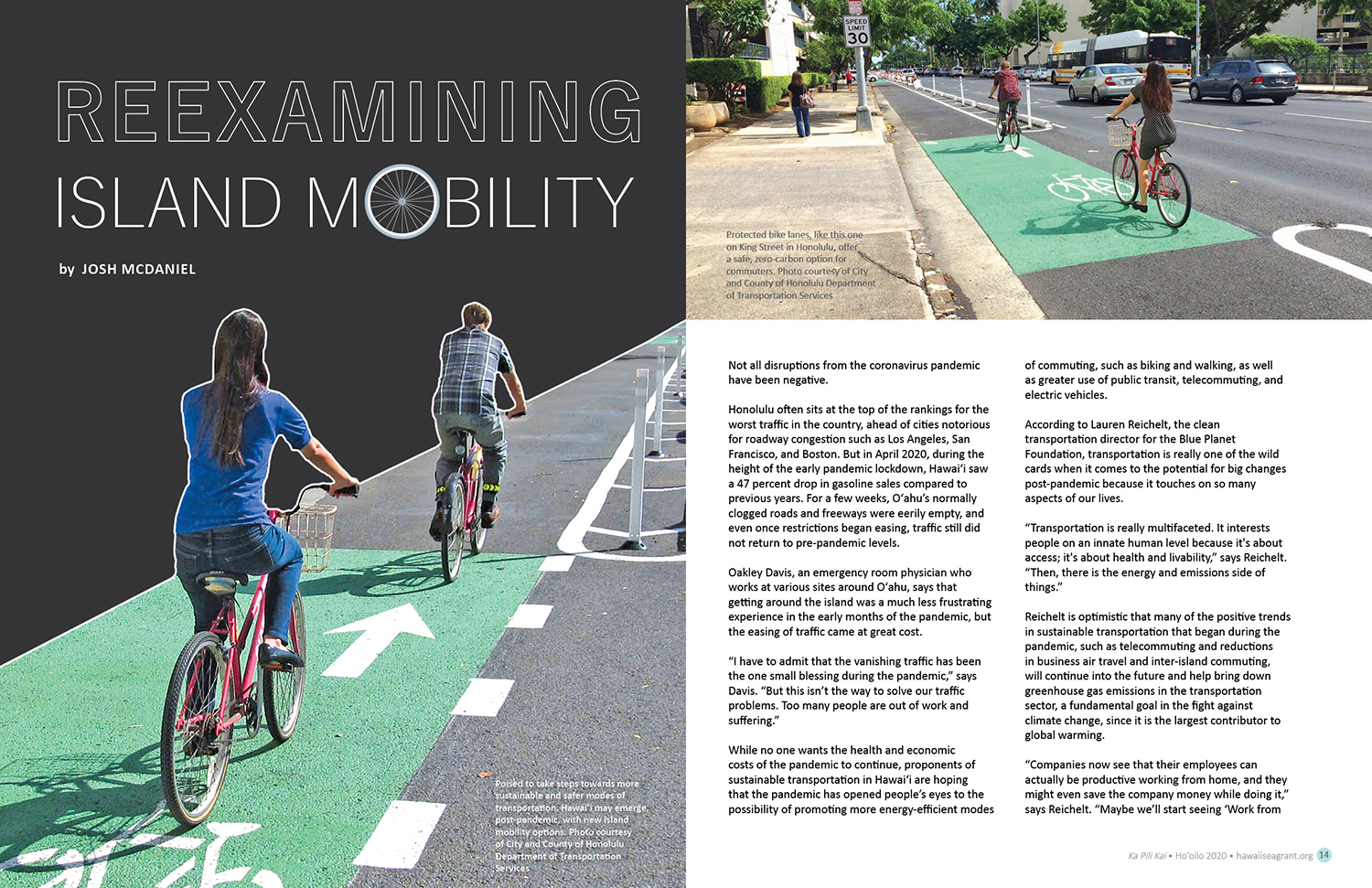

Reexamining Island Mobility

by Josh McDanielNot all disruptions from the coronavirus pandemic have been negative. Honolulu often sits at the top of the rankings for the worst traffic in the country, ahead of cities notorious for roadway congestion such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. But in April 2020, during the height of the early pandemic lockdown, Hawaiʻi saw a 47 percent drop in gasoline sales compared to previous years. For a few weeks, Oʻahu’s normally clogged roads and freeways were eerily empty, and even once restrictions began easing, traffic still did not return to pre-pandemic levels. Oakley Davis, an emergency room

Mālama During COVID-19

by Amanda MillinFor Celeste Connors, living with aloha extended far beyond the shores of Hawaiʻi. The former American diplomat worked overseas for 20 years and served as the White House director for Climate Change and Environment. But she is from Kailua, and it is her connection to host culture values of aloha, mālama, kuleana, and ʻohana that have driven her. “I was involved in negotiations at the highest levels of government,” says Connors. “I realize now that my actions were informed by host culture values having grown up in Hawaiʻi, which I wouldn’t have connected to unless I came home

Rebooting Hawai‘i’s Visitor Industry

by Shannon WianeckiDuring the last week of March 2020, the fallow sugarcane fields next to the Kahului Airport on Maui began to fill with cars. Hundreds, then thousands of nearly new Camaros, Jeep Wranglers, and SUVs appeared, parked bumper to bumper alongside the road. By the time Governor Ige issued a stay-at-home order in response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, the island’s entire rental car fleet—around 22,000 vehicles—had been put out to pasture. The global health crisis effectively pulled the emergency brake on Hawai‘i’s tourism industry. Across the state, car rental agencies, resorts, restaurants, and tour operations shut their doors,

Guidance for Using the Sea Level Rise Exposure Area in Local Planning and Permitting Decisions

This document is a supplement to the Hawaiʻi Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Report (“Report”; Hawaiʻi Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission, 2017) and the Hawaiʻi Sea Level Rise Viewer (“Viewer”) (both available at climate.hawaii.gov). The primary purpose of this document is to assist state and county planners, natural resource and infrastructure managers, and others with understanding and using the Sea Level Rise Exposure Area (SLR-XA) from the Report and Viewer in day to day planning and permitting decisions, particularly at the project or property-level scale (Figure 1). This guidance was developed in response to requests from county planning

Loko Iʻa Needs Assessment

This report is the first comprehensive compilation of the research ideas and needs within the community of fishpond managers, landowners, and stewardship organizations to inform adaptation of fishpond practices toward their resilience, adaptation, and sustainability in the face of a changing climate. It reflects the needs, interests, visions, and ideas of the Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa as documented in their collective and cumulative conversations in 2019. The report was synthesized by a collaborative of Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo, the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program, and the Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center. Download the pdf

IN THIS SECTION

Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Resources