During the last week of March 2020, the fallow sugarcane fields next to the Kahului Airport on Maui began to fill with cars. Hundreds, then thousands of nearly new Camaros, Jeep Wranglers, and SUVs appeared, parked bumper to bumper alongside the road. By the time Governor Ige issued a stay-at-home order in response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, the island’s entire rental car fleet—around 22,000 vehicles—had been put out to pasture.

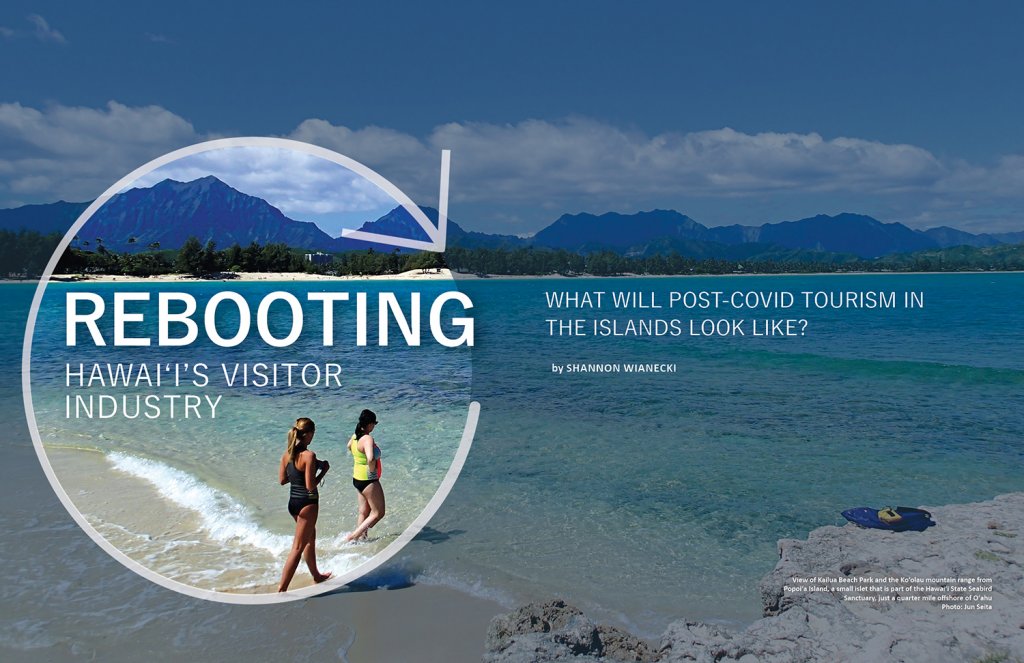

The global health crisis effectively pulled the emergency brake on Hawai‘i’s tourism industry. Across the state, car rental agencies, resorts, restaurants, and tour operations shut their doors, unsure when they might reopen. Airplanes all but disappeared from the sky. The average number of passengers arriving by plane each day in Honolulu dropped from 30,000 to less than 500. Nine months later, new testing and quarantine measures have allowed Hawai‘i’s visitor industry to slowly reboot. Residents wonder what will post-COVID-19 tourism look like?

People everywhere are asking the same question. The near total shutdown of tourism worldwide has forced government officials, business owners, and community leaders to examine their priorities and plot new trajectories. This unprecedented moment of pause is both a crisis and an opportunity.

“We need to save people’s lives and their livelihoods,” says James Mak, a University of Hawai‘i emeritus professor of economics. He recognizes the urgency to get the gears of business turning again, but having studied and written extensively about tourist industry issues for decades, he knows the re-opening shouldn’t just be speedy—it should also be strategic.

Tourism represents roughly a quarter of Hawai‘i’s economy. In 2019, the visitor industry supported 216,000 jobs statewide, yielded nearly $17.8 billion in visitor spending, and contributed more than $2 billion in tax revenue to state coffers. Without this influx of cash, a distressing number of local businesses will certainly close for good. Nevertheless, many kama‘āina (longtime residents) experienced the sudden absence of tourists as a relief. For the first time in memory, people living on O‘ahu saw uncrowded beaches and traffic-free streets. Locals were no longer outnumbered in their own neighborhoods.

The coronavirus shutdown revealed an existing fault line. Over the past ten years, as Hawai‘i’s visitor numbers have shot up, resident satisfaction has dropped in direct proportion. Surveys conducted by the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority demonstrate that island residents increasingly feel that tourism exists for the benefit of visitors at the expense of locals. It’s no wonder. Over 10 million tourists came to Hawai‘i in 2019. That’s more than seven times the state’s population. Meanwhile, when adjusted for inflation, visitors’ average daily spending has steadily decreased since its peak in 1988. More people are coming to Hawai‘i than ever before, they’re spending less, and residents are feeling the strain.

“Unless we do a better job of managing tourism, residents will suffer and we’ll be killing the goose that lays the golden egg,” says Mak. “At some point even the tourists who still think Hawai‘i is a dream destination will decide that this is no place to go. Especially on Maui and Kaua‘i, where tourism represents an even larger proportion of the economy than on O‘ahu, the problem is quite acute.”

Keani Rawlins-Fernandez serves as the Moloka‘i representative on the Maui County Council and believes that residents’ needs should be prioritized. “We should be designing our tourism industry around quality of life for residents,” she says. Her jurisdiction has been hit the hardest by the shutdown. In April 2020, Maui’s Kahului-Lahaina-Wailuku metropolitan area reported 35 percent unemployment—the highest rate anywhere in the United States.

As the council’s budget committee chair, Rawlins-Fernandez has a clear understanding of how tourism dollars ripple through her community. The State of Hawai‘i Department of Taxation collects a ten percent transient accommodation tax (TAT) on every hotel, condo, or vacation rental stay and distributes it to the counties. “Each year Maui County receives $23.4 million from the state fund,” says Rawlins-Fernandez. “This year, because of the shutdown, we anticipate receiving zero state TAT.”

That’s just one of many COVID-induced revenue shortfalls. Shuttered hotels and restaurants aren’t paying their usual fees for water, sewage, and solid waste. All of those vehicles parked in the cane fields represent significant loss of income for the county. Typically, every rental car on the road contributes about $150 per year in highway taxes and fuel charges. “We estimated a loss of 11,000 vehicles this year,” says Rawlins-Fernandez. That’s another $1.65 million erased from the books.

While acknowledging those losses, Rawlins-Fernandez contends that the costs of an overburdened tourist economy are equally significant and often go uncounted. Hawai‘i’s natural environment suffers from too much traffic. Marine researchers studying the state’s two most popular snorkeling spots, Hanauma Bay and Molokini Crater, say that in the absence of non-stop human visitors, they have observed changes in fish behavior, slight increases in fish abundance, and a return of apex predators. The clarity of the water at Waikīkī is startling. Coral reefs across the archipelago are getting a much-needed break from sunscreen and accidental fin-kicks.

Hawai‘i’s relatively frail infrastructure is getting a break, too. Hotels may not be paying for county services, but they aren’t using them, either. Less trash is ending up in island landfills and less sewage in treatment systems. “In West Maui, where most of our hotels and resorts are, there’s been a significant drop in treated wastewater from injection wells flowing into the ocean,” says Rawlins-Fernandez. “An average of 4-5 million gallons per day went down by 60 percent, and in South Maui it went down by 80 percent. The effect that waste has on the coral reef is substantial,” she says. “These are huge impacts.”

According to Mak, the problem isn’t just too many visitors; it’s too many visitors overwhelming vulnerable places. “Whether we have ten million tourists or two million,” he says, “there will still be hotspots where we have congestion, degradation of resources, and local residents being crowded out.”

New technologies have contributed to this effect, known globally as “overtourism.” Lower transportation costs made travel more affordable for the masses. Peer-to-peer apps spurred the proliferation of short-term vacation rentals, transforming quiet residential neighborhoods into DIY resort zones. Social media platforms broadcast “hidden” sites to an audience of millions. Any phone equipped with a GPS enables adventure seekers to stray from the beaten path into remote, ecologically fragile areas that don’t have the infrastructure to support such intrusion.

Such was the situation on the Hāna Highway prior to the March shutdown. Traffic on the scenic coastal road that snakes along the East Maui sea cliffs had swelled to an unsustainable level. Hundreds of cars and tour vans passed through per day, clogging one-lane bridges, parking illegally, and depositing people onto bushwhacked trails in search of waterfalls and caves. Local residents had resorted to blocking traffic and shouting at trespassers with bullhorns. “This is the community saying to the government, ‘If you’re not going to do something, we will,’” says Rawlins-Fernandez. “It should never get to that point.”

So, what’s the solution?

By its name, the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority (HTA) seems the logical place to look for answers, though historically its mission has been to attract as many visitors as possible to the islands rather than manage tourism or tourists’ experiences upon arrival. Following a 2018 audit, HTA’s management team has cycled through multiple chief executives and seen its state-funded budget slashed from $86 million to $55.2 million. Combined with COVID-19’s massive impacts on tourism, these challenges present HTA with an opportunity for positive change.

Dolan Eversole sees how HTA’s mission can be reshaped to focus on destination management. “Who manages the tourists once they’re here? That’s Hawai‘i’s big, outstanding question.” Eversole works for the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (Hawai‘i Sea Grant) and is researching how other states manage outdoor recreation through its Center of Excellence for Sustainable Coastal Tourism. He hopes Hawai‘i can borrow solid ideas from elsewhere. “Oregon has a very successful program,” he says. “In addition to “Visit Oregon,” their version of HTA, the state has a small but effective organization that deals with visitor management.” That team fanned out into communities suffering from overtourism and asked locals: “what would you like to change about how people visit your area?”

Like their Hawai‘i counterparts, Oregonians complained about excessive traffic, lack of parking, and congestion around waterfalls. Oregon’s visitor management team helped individual communities develop targeted solutions. One initiative got people out of rental cars and onto tour buses and bikes. Another used social media and text alerts to direct people to less crowded areas.

Some of the world’s most popular tourist destinations—London, Cinque Terre, Amsterdam—have turned to technology to solve some of the problems it helped create. London city officials promoted a mobile app featuring Mr. Bean, a comedic character who showcases hidden gems of the city. App users play along with Mr. Bean, earning vouchers that they can redeem in local boutiques. This engaging game supports small businesses and drives visitor traffic from the bottlenecked downtown into lesser-known neighborhoods.

Hawai‘i has some experience with actively managing visitor traffic. In 1990, the City and County of Honolulu teamed up with a group of concerned citizens and Hawai‘i Sea Grant to address serious overcrowding at the Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve. Back then, as many as 10,000 snorkelers would descend on the fragile marine reserve per day, trampling coral, feeding and harassing fish, and leaving a trail of trash in their wake. The community-driven management plan transformed the battered area. It brought the daily visitor count down to 3,000, charged admission and parking fees, and instituted an award-winning educational program administered by Hawai‘i Sea Grant. The new policies gave Hanauma’s marine ecosystem a chance to revive.

While certainly a success story, Mak says the bay’s management comes at high cost and could be improved. “We pay people to work the ticket booth. Residents don’t pay admission, but they have to stand in line like everybody else. Lines are long; unless you get there first thing in the morning there isn’t space. The 300 parking spaces could fill up by 7:30 a.m., and there’s no way of knowing that until you get there.”

An online reservation system could solve these problems. The state parks division recently implemented online reservations for Hā‘ena State Park on Kaua‘i. After a massive flooding event closed the park in 2018, residents decided they didn’t want to open back up to the same level of traffic as before. They worked with state officials to create a master plan. Visitors must now make parking reservations in advance which are valid for particular time slots. A new paved lot has 100 stalls, including 30 reserved for residents. The total number of daily visitors is capped at 900.

Rawlins-Fernandez sees this type of management as a potential solution for the Hāna Highway. “Hāna residents only need a certain number of people to come through to buy their banana bread and then they’re done. Let’s figure out how many people max out the benefit and make that the cap.”

Limiting traffic at popular spots only works to a certain extent. If the overall visitor count keeps increasing, the islands will continue to feel overcrowded. While state leaders can’t restrict the number of people traveling to Hawai‘i, Rawlins-Fernandez says planning commissioners can do something more powerful: freeze or even reduce the number of available hotel rooms and vacation rentals.

Meanwhile, HTA has been doing its best to evolve and meet the industry’s newly identified needs. At the start of 2020, before the shutdown, HTA introduced its new five-year strategic plan, which focuses on four pillars: brand marketing, community, Hawaiian culture, and natural resources.

Branding remains essential, says Kalani Ka‘anā‘anā, HTA’s director of Hawaiian cultural affairs and natural resources. “We operate in a highly competitive market, where other destinations are often closer and cheaper. It takes work to build travel demand to the Hawaiian Islands, and it’s not something that functions like a light switch we can turn on and off. We’re presently building the demand for years down the road.”

Just about everyone agrees that Hawai‘i needs to attract higher spending, lower impact visitors. Promotional campaigns can help by setting visitor expectations and correcting misinformation. “Throughout history we’ve struggled with the portrayal of Hawai‘i as this romanticized destination for pleasure and the misappropriation of Hawaiian culture in the process,” says Ka‘anā‘anā. By providing a more accurate picture of the Hawaiian Islands, their history, and the people who live here, HTA can cultivate a better, more respectful visitor base.

In September 2019 HTA launched a campaign called “Kuleana,” an apt Hawaiian term that means both privilege and responsibility. Videos demonstrate how to visit the islands respectfully, addressing hot-button issues of ocean safety, conservation, and culture. Translated into multiple languages, the videos appear on several airlines, in hotel rooms, and, thanks to geo-targeting technology, in visitors’ Facebook and Instagram feeds.

For the “Hawai‘i Rooted” campaign, HTA sought out respected community leaders— fifth-generation taro farmers, indigenous tattoo artists, celestial navigators, and kumu hula (master teachers in the art of hula)—and let them tell their stories in beautifully shot videos. “For so long, Native Hawaiians and local people in general weren’t the face of the Hawaiian Islands,” says Ka‘anā‘anā. “We’re taking back the narrative and sharing what makes our home special to us.”

Beyond marketing, HTA supports Hawaiian culture and arts by funding diverse community-based programs: everything from carving and weaving, to dance and puppetry. One of the projects that Ka‘anā‘anā feels most proud of is HTA’s recent collaboration with Bishop Museum and Kamehameha Schools to digitize a collection of Hawaiian language newspapers. The newspapers contain priceless historic and cultural information, and many are over one hundred years old and disintegrating.

HTA flew in a paper conservator from the continental United States and bought a high-resolution scanner large enough to fit the oversized newspaper pages. “This was a huge project for us,” says Ka‘anā‘anā. “It was unique in terms of HTA and tourism dollars supporting that kind of work. It heralds a new era in holistically understanding our destination and what our needs are.” When complete, it will be the largest digital resource of indigenous Hawaiian literature.

Ka‘anā‘anā takes a broad view of HTA’s role in the community. “We may not be the right organization to implement fixes, but we’re really good at being a convener, putting the right folks in the room.” He offers Laniākea Beach as an example. For years, the popular spot on the north shore of O‘ahu has been snarled with traffic as people pour out of tour buses and rental cars, crowding onto a narrow strip of sand in the hope of seeing basking sea turtles. HTA brought various stakeholders together to address the problem.

“We didn’t have jurisdiction, but we were able to get the mayor, hotel management, community leaders, as well as the Department of Transportation in the room together.” The brokered discussions led to new agreements addressing public safety, access, and parking. In addition, HTA sponsors Mālama Na Honu, a volunteer group that protects the sea turtles from harassment and helps to educate the public about Hawai‘i’s threatened marine life.

Out at Ka‘ena, the wilderness area at the northwestern tip of O‘ahu, HTA-funded information specialists interact with visitors, point out landmarks and seabird burrows, and make sure people don’t get lost or dehydrated. “This is quite literally their backyard,” Ka‘anā‘anā says of the specialists, who come from nearby communities and know this landscape intimately.

Dr. Pauline Sheldon, professor emerita at the UH School of Travel Industry Management, believes that tourism management should be community-driven. “The days of consultants flying in and writing reports and putting them on the shelf are over.” Ideally, community leaders would work together to create visitor experiences that are both meaningful and fun and help their neighborhoods thrive. “It’s going to take a real shift in mindset,” Sheldon says. “Instead of looking at tourism as an industry, we need to look at it as a tool of wellbeing for the destination. That’s what we call ‘regenerative tourism.’”

Sheldon demonstrated the concept of regenerative tourism in a recent essay exploring Waikīkī in 2025. In her vision of the future, electric service vehicles and public transit have eliminated the traffic jams on Kalākaua Avenue. Vibrant locally-owned businesses have supplanted the luxury-branded chain stores. Instead of shopping for imported souvenirs, visitors learn about Hawaiian culture in living museums, art hubs, and story-telling kiosks. Some high-rise hotels have been taken down, or transformed into resident housing, schools, and care centers for kūpuna (elders). A fantasy? Only if we lack the will to make it happen.

As Hawai‘i grapples with how to re-launch its tourist industry, one thing is certain: the metrics of success need to change. “For a long time the industry has tried to keep taxes down,” Mak says. “But those taxes generate benefits for local residents. So that attitude has to shift.” The old goal of max occupancy, getting “heads in beds,” has to be jettisoned forever.

First and foremost, Mak says, “we have to make sure people are safe. We need to do testing and contact tracing for coronavirus. Then we need to weigh the benefits of letting tourists back in incrementally. I don’t see overwhelming support on the part of the residents for bringing back 10.4 million tourists in 2021. I don’t see that happening.”

Ka‘anā‘anā wants to foster deeper conversations. “Fundamentally we have to talk about why we do tourism. People forget the intrinsic value of travel. If we continue to look at it as just an industry, we dehumanize it,” Ka‘anā‘anā says. “Tourism is people; tourism is relationships.”

A healthy travel industry enriches both visitor and host. It can serve as a bridge between communities, allowing them to experience the best of one another. The world’s fascination with the Hawaiian Islands isn’t likely to change any time soon—and that’s a good thing. “Hawai‘i has a unique opportunity to touch people in a special way,” says Ka‘anā‘anā. “There’s a mana [spiritual power] to this place that cannot be ignored.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE