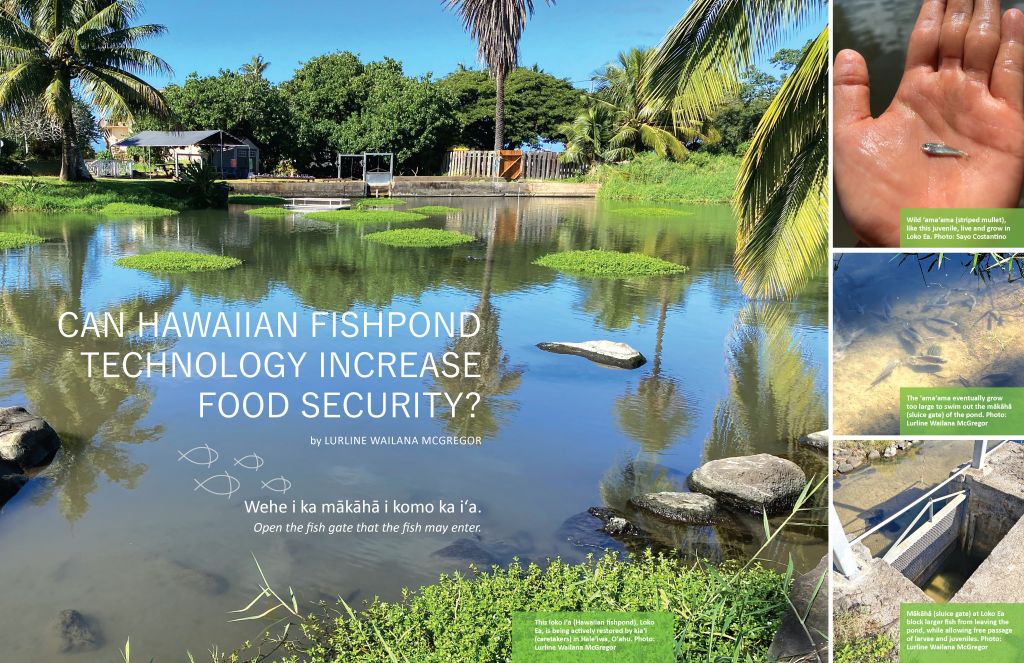

“Wehe i ka mākāhā i komo ka iʻa,” open the fish gate that the fish may enter, is an ʻōlelo noʻeau (Hawaiian proverb) referencing a strategy used to trap fish in the loko iʻa, as well as a trap for invading warriors. For over one thousand years, all it took to attract pua (juvenile fish) into the approximately 488 fishponds that Native Hawaiians built along the shores of the islands, was to open the gate, due to its innovative construction. These loko iʻa were abundant with many species of fish, including the revered ʻamaʻama (striped mullet) that fed the chiefs as well as the community that helped to build and care for the ponds. The kiaʻi, or caretaker of the loko iʻa, had knowledge that ranged from how and where to build the kuapā, or rock wall enclosure, to how to manage and sustain the loko iʻa, which required a deep understanding of fish life cycles, pond biology, tides, and moon phases. Kiaʻi skills, passed down through generations, assured a healthy population of fish and protection for the pua to grow. After the arrival of the Europeans, Hawai‘i experienced many changes, including the loss of traditional fishpond management skills. The fishponds also experienced environmental degradation from lava flows, terrestrial erosion that led to increased siltation, tsunamis and high-wave events, and invasive mangroves and other vegetation that encroached into the ponds.

The 1904 Report of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries published that in 1903, over 700,000 pounds of ʻamaʻama were harvested from the ocean and 100 loko iʻa in Hawaiʻi. The next one hundred years brought with it overfishing, diversion of freshwater streams, degradation of coastal ecosystems, and the destruction of nursery habitats, dropping the published report of the ʻamaʻama harvest to under 10,000 pounds in 2003, none of it from loko iʻa. Exacerbating the problems, climate change is yet another contributor to the decline of pua stocks.

A renewed interest in loko iʻa is bringing communities together to restore fishponds, but much of the knowledge about managing them has been lost. Food security is a long-term goal among the loko iʻa community, but there is much to learn and accomplish before this goal can be realized, including rebuilding native fish stocks in the ocean. Western technology can be used as a tool in restoring loko iʻa (i.e., providing aquacultured pua to stock loko iʻa).

“Since the early 1990s, there have been efforts to stock loko iʻa, specifically with ʻamaʻama,” says Dr. Kai Fox, University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program aquaculture extension specialist. “In the past, loko iʻa practitioners have asked for hatchery-raised fingerlings. When they’re introduced into the pond, though, it’s a shock [for them], going from a controlled environment into the wild. So there’s been mixed success, but generally poor survival.”

There are many reasons for the low survival rate, including differences in salinity, temperature, oxygen, predators, and lack of gut flora. “For it to be economically viable for the hatchery, they need to release the fish when they’re really small,” says Fox. While this makes it less expensive to produce aquacultured pua, it leaves them more vulnerable to a new environment at such an early stage in their development. “We are developing a pua boot camp, where fish from the hatchery can be acclimated to pond water and transitioned to life in the loko iʻa.”

In 2017, Conservation International (CI) Hawaiʻi partnered with three community based loko iʻa organizations to conduct a two-and-a-half-year project with three goals: 1) grow hatchery-produced ʻamaʻama pua to nursery-size fish; 2) secure a stable supply of ʻamaʻama pua to stock fishponds; and 3) support capacity building at the loko iʻa to create a viable aquaculture enterprise. The participating loko iʻa, which included Hale o Lono Fishpond on Hawaiʻi Island, Heʻeia Fishpond on Oʻahu, and Keawanui Fishpond on Molokaʻi, had to design and create a nursery habitat within their loko iʻa before they received the pua.

“ʻAmaʻama don’t like to spawn in captivity,” explains Dr. Chad Callan, who supplied the hatchery pua from Oceanic Institute and was the principal investigator for the project. “We had to inject the fish with certain hormones to bring them to maturation and get the females to ovulate, which is still only about fifty percent successful. It’s very expensive to do, and there isn’t a lot of money to support it.”

In each of the fishponds there were significant challenges during the study. The Heʻeia Fishpond had water quality issues due to the way the nursery ponds were constructed, which led to significant temperature and oxygen fluctuations and the ensuing loss of nearly all the fish. Keawanui Fishpond suffered significant predation from birds. At Hale o Lono loko iʻa in Keaukaha, the pua were doing well until the perigean tides, also known as King Tides, inundated the ponds and the fish were washed over the walls.

“The project was a success in that the fishponds were able to construct and design nursery habitats,” says Callan. “The fish initially did well and started growing, but we were unable to track them through to their full growth potential, so we know that the fish can be successfully produced here and acclimated and transferred to the fishpond. It’s costly, but it’s definitely feasible. So the question is how to pay for stocking ponds with hatchery-produced fish.”

Waikalua Loko Iʻa, in Kāneʻohe, Oʻahu, was also plagued with high mortality rates when hatchery-born fish entered the larger, or grow-out pond. NOAA’s National Sea Grant Office awarded Hawai‘i Sea Grant a two-year grant in 2021 to create an integrated, multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) project at Waikalua Loko Iʻa. Multiple aquatic species from different trophic levels will be farmed together in land tanks made up of water pumped from the loko iʻa and freshwater from Honolulu County. The top layer of the tank will contain hatchery born pua ʻamaʻama. The water from that tank will trickle down into a limu tank, then into an oyster tank, then into a sea cucumber tank. From there the effluent water will flow back into the fishpond.

“With this project we are hoping to become a nursery… We’re also using the limu and native oysters and sea cucumbers because it allows us to do restorative aquaculture, replenishing different nutrients in the water. The other species can also provide economic benefits,” says Rosalyn “Roz” Concepcion, the kiaʻi loko at Waikalua.

While hatcheries may be able to supply and distribute pua stocks to loko iʻa throughout the state, there are still many issues to overcome, not the least of which is securing sustainable funding. “We don’t want to be beholden to hatchery-raised pua. It’s not cost effective,” says Keliʻi Kotubetey, assistant executive director of Paepae o Heʻeia who was involved with the CI project. “It can be a part of the process, but the alternative is a reduced stock of wild mullet to produce babies, so wild stock enhancement is something we’re working towards in Kāneʻohe Bay.”

Vernon Sato, who spent his career in aquaculture and managing mullet and is still active with helping local communities restore their loko iʻa, sees the larger picture. “Stocking ponds can contribute to food security for Hawai‘i, but the greater benefit might be in appreciating the productivity of these ponds that were realized in ancient times. We now have the technologies to better understand the ecological balances within the kuapā. It seems that this is the opportunity to equip the next generations of kiaʻi to have a scientific as well as cultural appreciation of these amazing food production systems.”

While food security may be the long-term goal, the growing community interest and commitment to loko iʻa restoration in combination with modern scientific technology is an assurance that, like other cultural practices successfully revitalized, loko iʻa are bound to flourish again.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE