Quiet. For the first time in generations, the schools of ulua, pāpio, and ‘o‘io glinting across the outer edge of Hanauma Bay’s crater experienced relative silence. The perpetual din of thousands of thunderous splashes and shrill voices reverberating from the shoreline fell away, and the inner bay became perplexingly inviting. The humans had retreated overnight, a measure taken to slow the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leaving a world newly open to ocean wildlife.

But while nature has reaped benefits from COVID-19 shutdowns across the islands, humans are left to reflect on the impact of our usual presence, and how to return with gentler hands.

The virus had an immediate and dramatic effect on Hawaiʻi’s tourism industry, and thus much of the flow of people to the state and county beaches. Even before Governor David Ige issued a statewide stay-at-home order on March 25th, 2020 and a 14-day quarantine period for all incoming visitors the next day, traffic into the islands had slowed substantially. Cruise ship arrivals into Hawai‘i fell by two-thirds in March, and compared to previous years, March arrivals into the state by plane had fallen by 50 percent.

In the following weeks, additional public health measures were taken by state authorities to combat COVID-19. In mid-April, the state closed Hawai‘i’s beaches to most activities outside of exercise, presenting another deterrent that kept people away from the water’s edge. In about a month, the archipelago’s network of beaches and parks went from bustling with many tens of thousands of tourists and kama‘āina, to being virtually empty.

Local nearshore wildlife has certainly noticed the conspicuous change. Hanauma Bay, O‘ahu, the state’s first Marine Life Conservation District, went from a few thousand visitors daily to essentially none in the blink of an eye, and it only took a few weeks for researchers monitoring the site to notice changes in the beloved snorkeling destination’s coral reef ecosystem.

Dr. Ku‘ulei Rodgers, principal investigator at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology’s Coral Reef Ecology Lab, has been studying the state’s reefs for decades, with particular close attention to Hanauma Bay, monitoring the marine ecosystem there since the late 90s. She and others observing the bay following the COVID-19 closures have noticed a swift change in the reef’s structure and function.

“We are seeing much larger fish, like some big ulua, more schools of pāpio that are coming in,” Rodgers says, “and movement of some of the large schools that used to stay in one segment [of the cove] moving now to another segment.”

The fish also appear to have become more comfortable around humans in the Bay, says Rodgers, swimming much closer than they would before. She and her colleagues are trying to quantify this change with further study.

The critically-endangered Hawaiian monk seals, occasional visitors to the Bay, are enjoying a freer reign as well, exploring and hauling out in locations usually packed with people.

“They’re lying right in front of the Keyhole [lagoon], right in front of the lifeguard stand,” says Rodgers.

Even Hanauma’s water has changed. Recent work by Rodgers and her team revealed that in the wake of the closure, the reef’s waters are 42 percent clearer than when the Bay is fully open, and 18 percent clearer than on the Tuesdays that the Bay has traditionally had its weekly one-day closure. Rodgers says this shows “that one day is not making that much of a difference to the water clarity.”

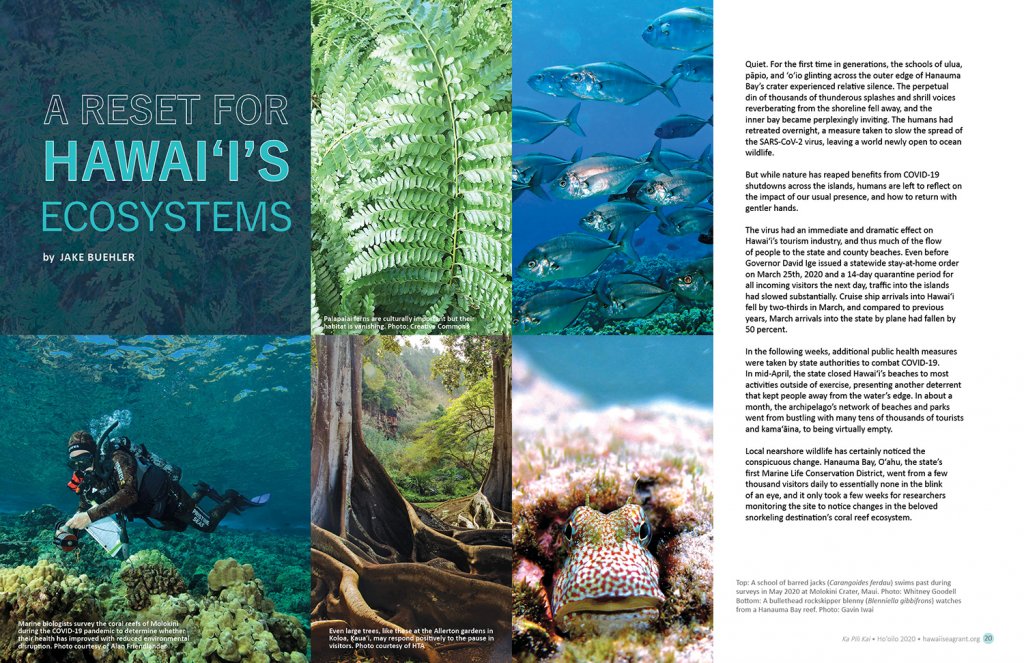

At another location that attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors a year off Mauiʻs coast prior to COVID-19, Molokini Crater, the story is similar. As commercial boat traffic and crowds disappeared, wildlife rebounded.

“You go out there and there’s big schools of fish, there’s ulua, there’s ‘ōmilu, dolphins,” says Dr. Alan Friedlander, principal investigator at the University of Hawai‘i’s Fisheries Ecology Research Laboratory.

Friedlander and his team have been monitoring Molokini, and conducted surveys of the ecosystem a few months after the COVID-19 closures. His lab’s research on the reef had previously shown that once there is a critical mass of boats and people out on the crater, larger predators like ulua and sharks go elsewhere.

Now that these pressures have temporarily evaporated, the animals have returned.

While these idyllic scenes of returning wildlife evoke a sense of ecological healing, the pandemic is having negative impacts for some island ecosystems and their human stewards focused on recovery efforts.

As schools across the islands closed, the fundamental operation of Healthy Climate Communities, a non-profit conservation organization with a focus on climate change, went through an abrupt shift. A substantial portion of the volunteers that have traditionally partnered with Healthy Climate Communities to help restore native marshes and forests on O‘ahu are connected to schools and other institutions that have ceased operations during the pandemic. Education and outreach has gone remote, says executive director Lisa Marten, in the form of virtual reality field trips.

“We are shut down right now. Schools are not doing field trips; they are not receiving in-school workshops,” she explains. “So those activities cannot happen right now.”

Marten, her colleagues, and a network of community volunteers have been working to restore habitat and native species in windward O‘ahu’s Hāmākua Marsh and Pu‘u o Ehu Hillside. Much of this work, says Marten, involves planting of native, sometimes endangered flora, and removal of invasive vines and haole koa trees, which choke out native plants.

But without the normal flow of organized groups and their many hands to work in these habitats, “there’s a lot to do,” says Marten, as the invasive plants keep growing. “Invasive species don’t know that there’s COVID. They don’t care.”

The combination of sudden biological richness and freedom gracing nearshore ecosystems and the partial disruption of stewardship in others requires two clear-eyed evaluations. The first addresses how humanity is inadvertently tamping down beneficial environmental conditions under normal, non-pandemic circumstances. The second requires a new way of thinking about ecological stewardship in a time of necessary physical isolation.

Central to an approach to achieve sustainability beyond the shores of Hanauma and Molokini is the realization that interacting more harmoniously with ecosystems doesn’t preclude the presence of even large numbers of people. The Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance, which blossomed in the latter half of the 20th century, produced a grassroots movement of conservation and ecological restoration efforts from a Hawaiian biocultural perspective, where resource management is framed through a merger of indigenous cultural and biological values. This approach draws on the rich knowledge of Native Hawaiian communities and traditional practices of natural resource stewardship.

An example of how perspectives from traditional ways of life can shed light on subtle behaviors that can modify community resources comes from the boundary of land and sea. Kāwika Winter, an ecologist at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology and reserve manager at the He‘eia National Estuarine Research Reserve on O‘ahu, describes the seemingly innocuous act of walking in the very edge of the surf along the beach, which is where young fish congregate to hide from predators.

“When the tourists are always walking in those areas and splash around those areas, it scares the baby fish away into the deeper water where they get eaten by predator fish,” explains Winter. “And then after decades and countless fish generations of that happening, that contributes to a decline in our fishery.”

For this reason, says Winter, the practice of walking up against the water was sometimes banned in old Hawai`i.

“You were only allowed to walk in the shadows along the vegetation,” he says. “The ocean is the community’s refrigerator, so you don’t want to scare the food out of your refrigerator just because you’re walking in the wrong spot.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has given people in Hawai`i the rare opportunity to reflect on impacts of business as usual on the natural environment, and the potential for more responsible ways forward.

For Kekuhi Kealiʻikanakaʻoleohaililani, kumu hula and Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner at Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, the potential for long-term changes in approaching stewardship comes down to what happens when the pandemic eventually abates.

“How we make this long-lasting is a simple exercise of being reflective,” she says, noting that humanity has been given a “big, fat mirror” to contemplate.

“And the challenge is: are we going to continue in that kind of consciousness or are we waiting to go back to the way it was?”

Huihui Kanahele-Mossman, a cultural practitioner and kumu hula of Hālau O Kekuhi, has seen this reflection already play out in her own practice: hula. With dancers spending less time in the “throes of performance” these days, says Kanahele-Mossman, there’s more opportunity to tend to the resources so integral to their practice.

One such component is palapalai, the lace fern. The plant is immensely important in hula, used as an adornment on the kuahu (altar) and upon the dancers themselves. The native ferns grow in vanishing pockets of forest, and are not abundant, says Kanahele-Mossman.

“What I see happening around is people actually taking care of their own patches of palapalai, wherever they are,” she says. “And being able to grow it out so that they have a resource without having to go into the forest [to gather it].”

Kanahele-Mossman also recognizes that the changes recently documented in nearshore habitats following the shutdowns provide insights into ecological conditions in the past.

“Now we get to observe things that our kūpuna have observed,” she says. “Now we start to understand the data they passed down to us in chants.”

The next steps, she adds, are for cultural practitioners to record these changes, in chants or stories, for future generations.

Others across the islands are adapting to pandemic conditions while stewarding sensitive habitats. For Marten at Healthy Climate Communities, the loss of large, organized groups for restoration work has meant a shift to small family groups, often looking for outdoor community service to combat shutdown idleness.

“Volunteers that are not connected to schools can still come out,” she says. “Our space is very COVID-friendly. We have no indoor areas.”

Another key route to constructive reflection, says Winter, is seeing natural resources through an island-based prism.

“We’ve been inundated by this foreign, continent-based thinking that ‘oh, well, after we use up all the resources here, we can just go somewhere else and use those resources’,” says Winter, noting that this is incongruous with traditional views of what sustainable life in the islands requires. “If we’re going to thrive in this place, we need to take care of this place. Because this is all we have.”

The utility of incorporating thinking from our island heritage and cultural roots isn’t just limited to life in the archipelago. The Hawaiian Islands are something of a scalable model to other places around the globe, says Winter, since the diversity of ecological processes is comparable to what you find on larger landmasses, just scaled down.

“How then,” asks Winter, “can the world learn from how our ancestors managed limited resources to thrive?”

He points to a Hawaiian proverb: he wa‘a he moku, he moku he wa‘a, or “The canoe is an island, and the island is a canoe.”

“When our ancestors were voyaging around the Pacific, on canoes, they had to manage the limited resources of a canoe until they got to the next island,” Winter explains. “And just because you got to an island, you don’t start thinking differently. […] You just scale it up to an island.”

The trick, says Winter, is adopting the perspective these ancestors used for canoes and islands and scaling up to the largest island of all, planet Earth.

“Because that’s the only way our civilization is going to thrive in the Anthropocene.”

Winter says that because of COVID-19, he and other colleagues who encourage biocultural research and conservation approaches are having some success in communicating that thinking to people in the islands that have never considered it before. The pandemic has been something of a wake-up call.

Kealiʻikanakaʻoleohaililani also notes that in recent years, learners at her hui from a diversity of stewardship roles, technicians, to ecologists, to policy-makers, have become markedly committed to understanding and working within this island perspective.

“They’re all questioning, ‘what more can I do in my little kuleana (reciprocal responsibility to the land)?’”

Perhaps this moment’s real silver lining, far greater than the temporary boon for wildlife, will be navigating out of our current Long Pause* by stepping out of quarantine, and into a canoe.

*The Long Pause refers to a mysterious hiatus in Polynesian voyaging history of about 2000 years. This gap occurred between the settling of West Polynesia and the later rapid expansion into East Polynesia (1500-500 years ago).

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE