Not all disruptions from the coronavirus pandemic have been negative.

Honolulu often sits at the top of the rankings for the worst traffic in the country, ahead of cities notorious for roadway congestion such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. But in April 2020, during the height of the early pandemic lockdown, Hawaiʻi saw a 47 percent drop in gasoline sales compared to previous years. For a few weeks, Oʻahu’s normally clogged roads and freeways were eerily empty, and even once restrictions began easing, traffic still did not return to pre-pandemic levels.

Oakley Davis, an emergency room physician who works at various sites around Oʻahu, says that getting around the island was a much less frustrating experience in the early months of the pandemic, but the easing of traffic came at great cost.

“I have to admit that the vanishing traffic has been the one small blessing during the pandemic,” says Davis. “But this isn’t the way to solve our traffic problems. Too many people are out of work and suffering.”

While no one wants the health and economic costs of the pandemic to continue, proponents of sustainable transportation in Hawaiʻi are hoping that the pandemic has opened people’s eyes to the possibility of promoting more energy-efficient modes of commuting, such as biking and walking, as well as greater use of public transit, telecommuting, and electric vehicles.

According to Lauren Reichelt, the clean transportation director for the Blue Planet Foundation, transportation is really one of the wild cards when it comes to the potential for big changes post-pandemic because it touches on so many aspects of our lives.

“Transportation is really multifaceted. It interests people on an innate human level because it’s about access; it’s about health and livability,” says Reichelt. “Then, there is the energy and emissions side of things.”

Reichelt is optimistic that many of the positive trends in sustainable transportation that began during the pandemic, such as telecommuting and reductions in business air travel and inter-island commuting, will continue into the future and help bring down greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector, a fundamental goal in the fight against climate change, since it is the largest contributor to global warming.

“Companies now see that their employees can actually be productive working from home, and they might even save the company money while doing it,” says Reichelt. “Maybe we’ll start seeing ‘Work from Home Wednesdays’ or ‘Telecommute Tuesdays.’ That alone could decrease travel impact by 20 percent each week.”

However, not everyone has the luxury of being able to telecommute to work. And one of the big lessons of the pandemic is that we rely on “essential workers” to keep our grocery stores, pharmacies, and hospitals operating smoothly. A report from TransitCenter found that many essential workers—2.8 million across the country—rely on public transit to get to work.

The same is true in many areas of Oʻahu. According to the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation, nearly 200,000 people used the Oʻahu bus system daily before the pandemic. Ridership plunged to 58,000 per day in April 2020. And while many buses were running far below capacity, public transit was a lifeline for essential workers who, despite their fears, still had to get back and forth to work.

Renee Espiau, the Complete Streets administrator for the City and County of Honolulu, praises the dedication of bus drivers and other transit employees who have been working to keep the buses safe and running, adapting to new cleaning and disinfecting protocols.

“TheBus never stopped running, even through the early weeks of shelter-in-place,” says Espiau “It was the only vehicle still out on the street because it’s something that the City is very committed to, and very proud of its service.”

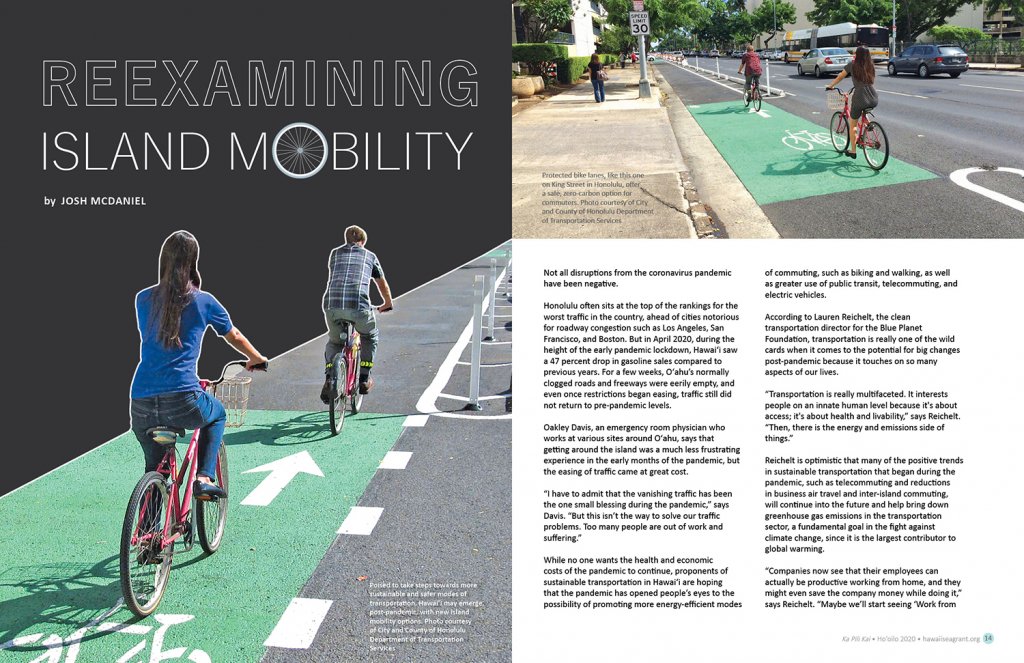

The Complete Streets program aims to create a comprehensive, integrated network of streets that are safe and convenient for all roadway users, whether they are traveling by foot, bicycle, bus, or automobile. The program is the driving force behind a number of multi-modal infrastructure projects in Honolulu, including the construction of protected bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly curb extensions, and a bus-only lane on King Street, one of Oʻahu’s main thoroughfares.

Supporting transportation equity is also a key principle of Complete Streets, and Espiau says that one of the biggest concerns is providing mobility access for low-income families that may not have automobiles. Other concerns are creating safe pedestrian networks for children who have to walk to school, and for older residents who can no longer drive and must get around on foot.

“We’ve invested billions of dollars into our roadway infrastructure. So, if you have the means to have a car, you have a large, relatively safe network to get you anywhere you want,” says Espiau. “If you don’t have the luxury of a car, you have fewer options, and that’s what we are working to address.”

Espiau further explains that Oʻahu has one of the best bus systems in the country, but often when passengers are let off the bus, they find themselves in a place that was not designed for pedestrians. Complete Streets is using data to identify high-need areas for upgrading pedestrian and biking infrastructure.

The emphasis on expanding infrastructure for bicycles is coming at a time when bicycle sales are at record levels. The bicycle aisles at big box stores are empty, and smaller independent shops are having a hard time keeping affordable family bikes (those under $1,200) stocked.

The Kalākaua Open Streets program was a collaboration between the City and County of Honolulu and Hawai‘i Bicycling League to support alternative transportation (and to provide an economic boost to the tourism-centered businesses hit hard by the pandemic). Officials blocked off vehicle traffic on Kalākaua Avenue — the main thoroughfare in Waikīkī — on Sunday mornings for six weeks to allow cyclists, pedestrians, and skateboarders to freely access the road.

It remains to be seen whether the people buying bikes for some socially-distanced exercise during the pandemic will turn into full-fledged bike commuters after the pandemic. If they do, they will find more bike-friendly improvements in Honolulu, including protected bike lanes and multi-use paths, with more planned or under construction.

Makena Coffman, the director of the Institute for Sustainability and Resilience at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, believes the surge in bike sales is great news and is hopeful many of the new riders will continue riding, but believes much more work is needed.

“We have an amazing bike master plan for Oʻahu. And if a fraction of the recommended paths are laid down, I think we would see a meaningful uptick in ridership,” says Coffman. “But to put it in context, only 1 percent of commuters bike to work. We have a long way to go.”

The biggest piece of the sustainable transportation puzzle on Oʻahu is the long-awaited, 20-mile Honolulu rail line, which extends from the swelling suburbs of western Oʻahu into downtown Honolulu. The rail line is expected to transform how residents and visitors move around that part of the island. Officials project that the railway will remove 40,000 cars from Oʻahu roadways when the trains are fully up and running (now projected for 2025).

Harrison Rue, the community building and transit-oriented development administrator for the City and County of Honolulu, says the city and county are focused on connecting neighborhoods near the 21 stations along the rail line with multiple forms of access, including public transit, pedestrian, and bicycle.

“We have plans for all the areas along the whole rail alignment, and multi-modal connectivity is a big part of that,” says Rue.

Of course, uncertainty is high, and it is difficult to predict how the impacts of the pandemic on our mobility and economy will affect transportation in the long-term. The continuation of many of the positive trends depends on whether the current situation lasts for months or years. That said, everyone agrees this is a time of change, and that the novel experiences of driving on empty freeways and roadways and getting around by bicycle, have awakened people to new possibilities. That awakening could lead to demand for a more sustainable and equitable transportation future.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE