When COVID-19 shut off the lights in schools throughout Hawai‘i, it starkly illuminated long-ignored cracks and constraints in its educational system. The crisis-mode quick fix—using modern technology to create virtual online schooling—spotlighted age-old problems and exposed new ones.

Not everyone had access to the internet, and a lot of households couldn’t afford service, highlighting a “digital divide.” Many teachers hadn’t received training in online instruction. And students, boxed in to their screens and homes, felt isolated and unmotivated.

“The pandemic has indeed made very visible the many warts that have grown upon the skin and the soul of our 1800s Industrial Age education system,” said Philip Bossert, executive director of the Hawai‘i Association for Independent Schools, comprising 100 independent K-12 schools.

Two decades into the 21st century, school systems still largely herd kids into crowded four-walled classrooms where teachers are asked to feed them a standard menu of siloed academic subjects—science in fourth period, history in seventh—and then test them on how much they have digested. Mandated curriculums can stifle creativity among both teachers and students, and standardized tests don’t adequately assess students’ abilities.

“Sure, everyone needs to count and read, but we ought to be trying to figure out what each child’s interests and capabilities are and foster their ability to pursue those,” Bossert said. “We should take an approach that seeks to realize the full human potential of each individual student, rather than form them to fit our industrialized society.”

COVID-related school closings leave no choice but to look beyond the stubborn four-wall classroom concept, said Tara O’Neill, a professor at the College of Education at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UHM). This triage moment, she said, has reopened society’s eyes to the value of education, forced us to reconsider long-tolerated, outdated practices, and catalyzed us to reimagine teaching and learning environments.

“That could be really exciting,” O’Neill said. Many ideas have long been on the table and have already taken seed in Hawai‘i’s fertile education community.

Spanning the digital divide

To lessen the digital divide immediately, the Hawai‘i Department of Education has instituted “learning hubs,” where students can safely come to use Wi-Fi, and “mobile learning labs,” vehicles offering Wi-Fi that travel to areas on various islands. But long-term solutions won’t be quick because of a long-standing failure to invest in infrastructure, said Michael Menchaca at the UHM College of Education

In the past, the U.S. government recognized the value of providing essential services to all citizens: transportation infrastructure, electricity in rural areas, and universal postal service. But internet access was left to for-profit companies, which have little financial incentive to extend broadband access to everyone and charge rates that some people can’t afford.

“Broadband is an essential service that people today require to be educated,” Menchaca said. “Other countries provide rebates or grants to ensure minimum levels of access to their citizens.”

“There’s also been a lack of investment in teacher professional development for digital skills,” he said. “Teaching online requires additional skills to do well.”

Menchaca is chair of the Department of Learning Design & Technology, which trains educators seeking innovative ways to integrate the latest technologies for teaching and learning. In five months after the pandemic began, he had conducted more than a dozen professional development workshops online with nearly 500 teachers from many institutions.

“Some of the most dedicated educators I’ve worked with are from really remote locations without adequate infrastructure, such as American Samoa and Palau, many of whom attended workshops on their phones,” he said. “Teachers are realizing the need to change and gaining new skills to take advantage of the technology and work with students in new ways.”

Thinking outside the curriculum standards box

Here’s an example of what’s possible beyond the four-walled classroom, said O’Neill, a former middle school science teacher. Students could be launched to observe something they are curious about—say, birds in their communities. They gain skills to find information online, and along the way pick up core curriculum concepts in biology, evolution, and ecosystems. They analyze their data. Maybe develop an app to track bird calls.

Such a teaching strategy incorporates several well-known pedagogical concepts. In educational parlance, it is learning that is “experiential,” “project-based,” “interdisciplinary,” and “place-based.” Research indicates these practices promote “students who become more self-directed learners and independent thinkers,” O’Neill said. Students still learn core curriculum concepts, plus more.

“Teaching isn’t about telling students about stuff. Today, all the info is already online,” she said. “Teachers facilitate students’ ability to process information. They help make knowledge meaningful to students.” A proven way to accomplish that is teaching content within a context, using communities as classrooms, letting students see concepts in action in the real world, and guiding them in applying their knowledge to benefit their communities.

O’Neill has championed these ideas as director of a master’s program in the College of Education at UHM called STEMS². It develops teaching practices integrating science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) with the social sciences and sense of place (S²).

Connecting to the real world

On the same campus, Linda Furuto has demonstrated that seemingly abstract concepts come to life for students when applied to the real world. Growing up in Hawai‘i, she struggled with math—until she began to see it all around her: in the geometric shapes of the menpachi fish that she saw spearfishing; in the calculations she needed to maximize her time underwater; and in the trigonometry of constellations that Indigenous navigators used to cross oceans.

She earned a Ph.D. in math education and helped build the math program at University of Hawai‘i-West Oʻahu, incorporating the field of ethnomathematics.

“The world is our textbook,” she said. Students record sound waves from marine life to study amplitudes, wavelengths, and frequency, for example. They use historical data in mathematical models of climate change and biodiversity to chart a course for the future.

“Students make the connections that mathematics has existed since the beginning of time and is embedded in global cultures,” she said. Those connections overcome math adversity and anxiety. Student enrollment in math courses at UH-West O‘ahu grew from 940 when she arrived in 2007 to 2,361 in 2013. She moved to UH Mānoa, which officially approved the world’s first institutionalized program in ethnomathematics in 2017. In 2018, the Hawaiʻi Teacher Standards Board approved adding an official field of licensure in ethnomathematics, the first in the world.

Expanding into a larger community

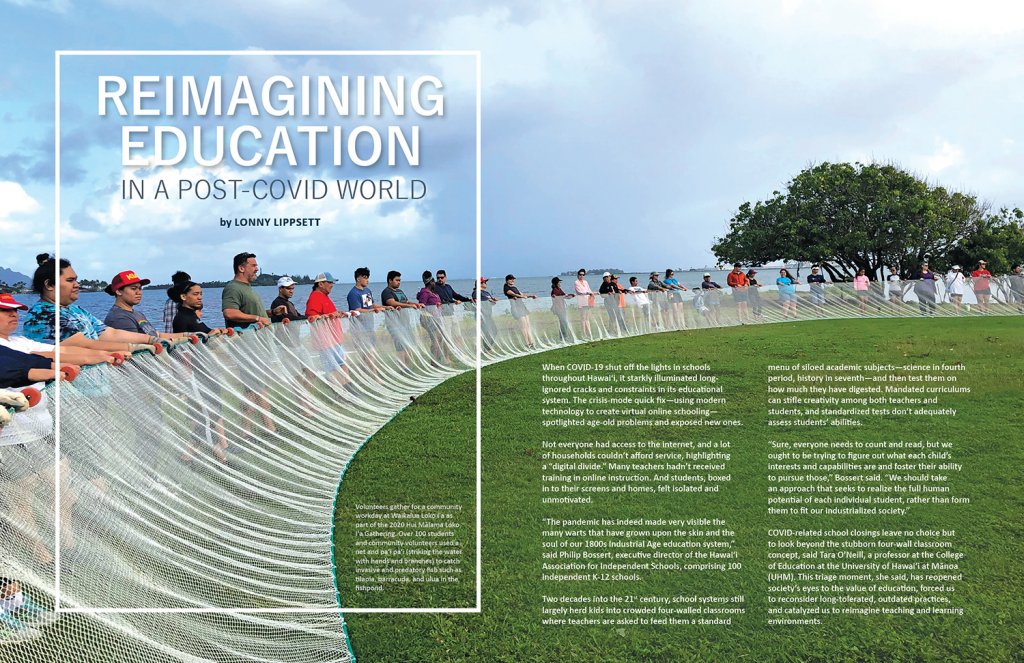

“The community is the classroom” is Herb Lee Jr.’s mantra. A mile from where he grew up on Oʻahu was Waikalua Loko fishpond, an extensive indigenous aquaculture system constructed by Hawaiians some 350 years ago.

In the mid-1990s, he spearheaded efforts to buy and preserve the land as an educational site. In 1998, a teacher brought Native Hawaiian students who weren’t doing well in school to the pond, and Lee enlisted the help of Clyde Tamaru, a University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program extension agent, to show them the science, engineering, history, and culture embedded in Waikalua Loko. “We saw this amazing transformation in nine months,” Lee said. “They were eager to learn.”

Eager to expand this mode of learning, Lee brought together educators who were awarded a grant under the Native Hawaiian Education Act to develop experiential, culture-based, place-based curriculums to teach science, math, social studies, language, and arts centered around the fishpond.

Under the auspices of the nonprofit Pacific American Foundation that Lee heads, the program has since expanded into the Aloha ʻĀina (“love of the land”) Curriculum. More than 6,000 teachers and 100,000 students have used it.

COVID’s shutdown of standardized testing also compels educators to think of other ways to assess students, Lee said. One idea is called hōʻike (“to show knowledge”). Instead of silently filling in multiple-choice questions, students at the end of fifth, eighth, tenth, and twelfth grades create presentations that demonstrate their knowledge and technological skills.

“They sit in front of teachers, students, community partners, and parents who ask them questions to gauge the depth of their learning, both social-emotional and intellectual,” he said.

“In this COVID time, because we cannot stay within the four walls of school anymore, teachers, administrators, and parents are looking for new ways to teach,” Lee said. “For all the bad that has come with COVID, this may be a positive tipping point for education.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE