PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS

See something of interest? Complete a publication request to order a digital or hard copy.

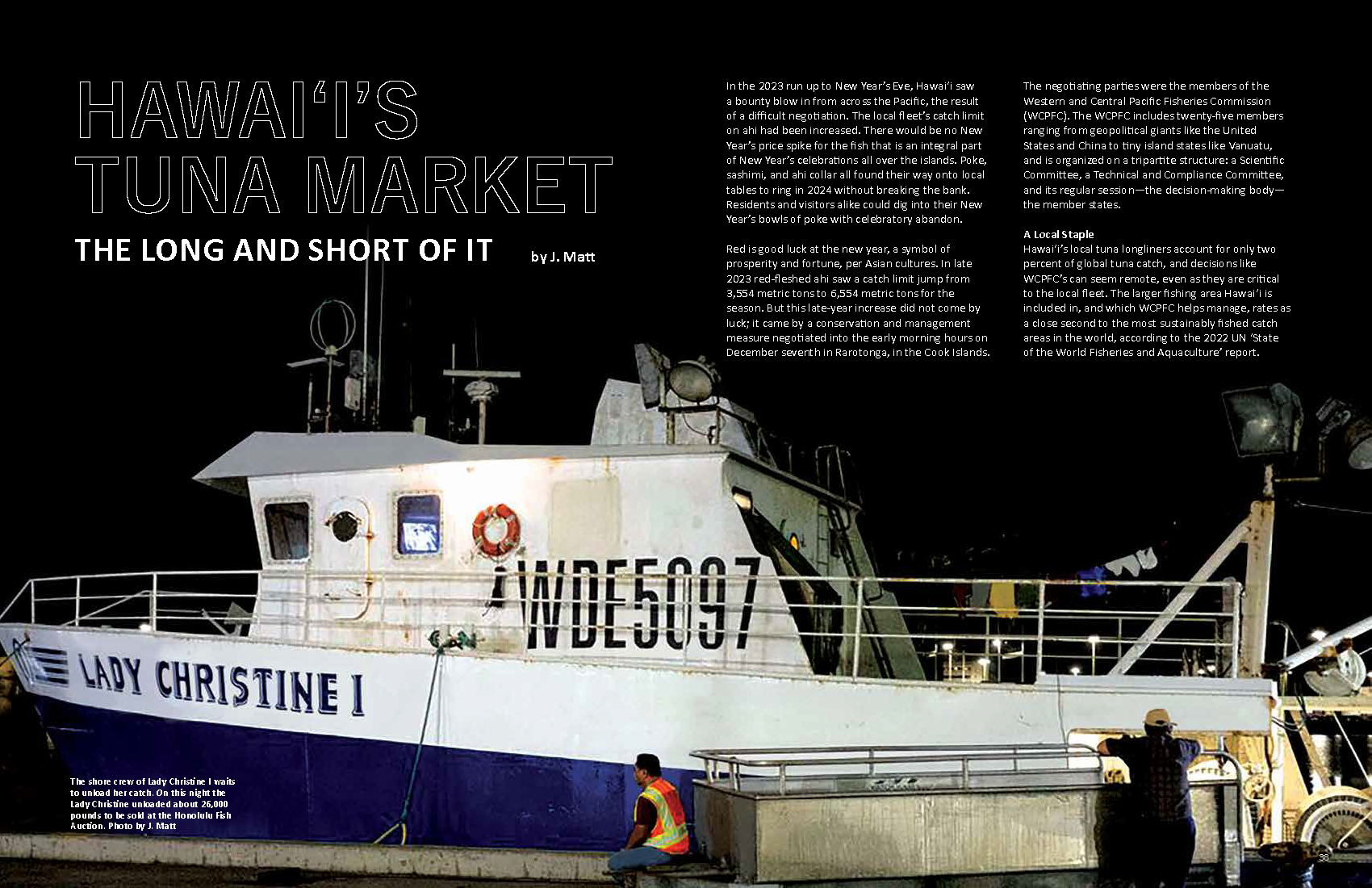

Hawaiʻi’s Tuna Market

by J. MattIn the 2023 run up to New Year’s Eve, Hawai‘i saw a bounty blow in from across the Pacific, the result of a difficult negotiation. The local fleet’s catch limit on ahi had been increased. There would be no New Year’s price spike for the fish that is an integral part of New Year’s celebrations all over the islands. Poke, sashimi, and ahi collar all found their way onto local tables to ring in 2024 without breaking the bank. Residents and visitors alike could dig into their New Year’s bowls of poke with celebratory abandon. Red is good

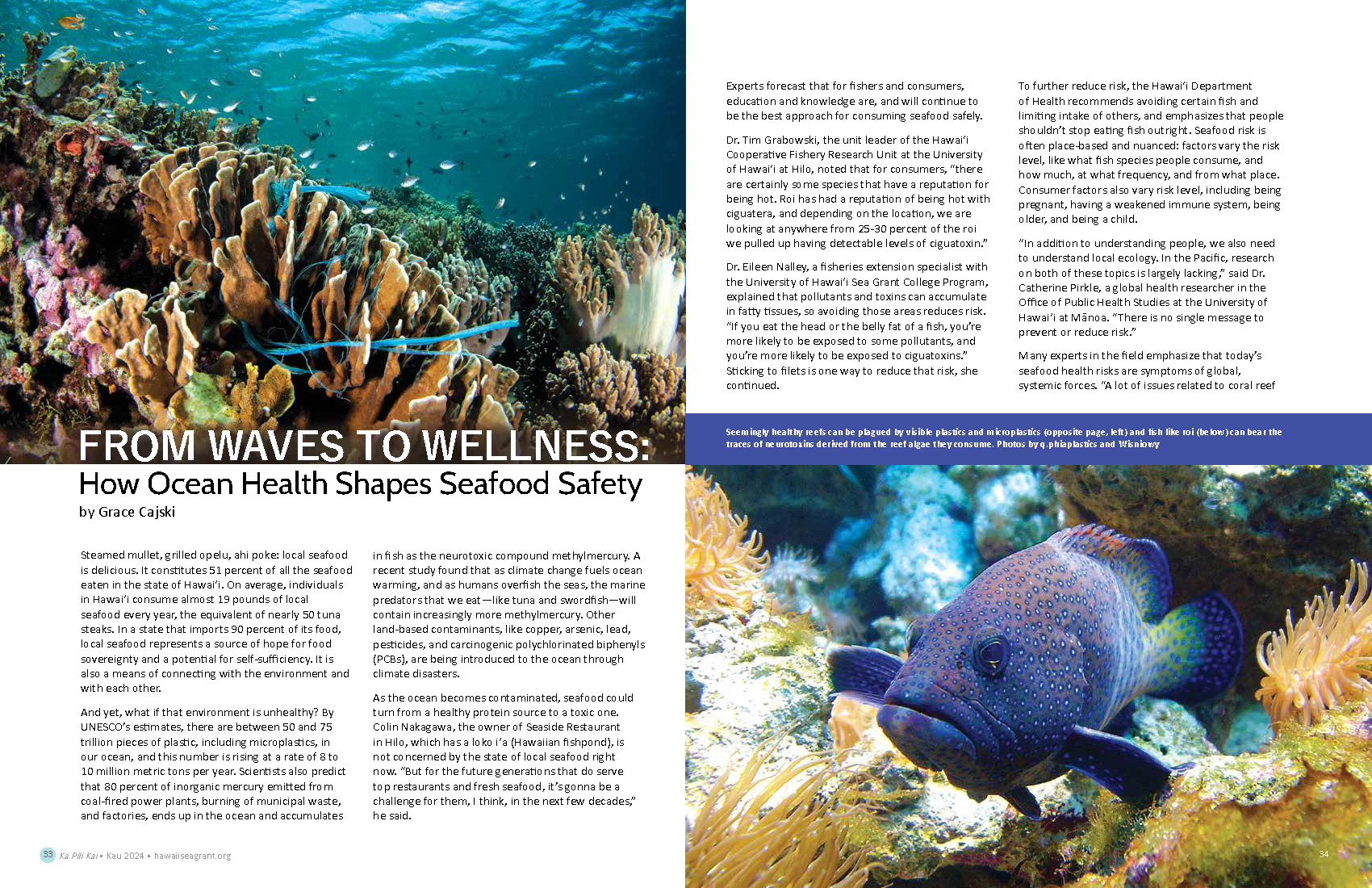

From Waves to Wellness

by Grace CajskiSteamed mullet, grilled opelu, ahi poke: local seafood is delicious. It constitutes 51 percent of all the seafood eaten in the state of Hawaiʻi. On average, individuals in Hawaiʻi consume almost 19 pounds of local seafood every year, the equivalent of nearly 50 tuna steaks. In a state that imports 90 percent of its food, local seafood represents a source of hope for food sovereignty and a potential for self-sufficiency. It is also a means of connecting with the environment and with each other. And yet, what if that environment is unhealthy? By UNESCO’s estimates, there are between

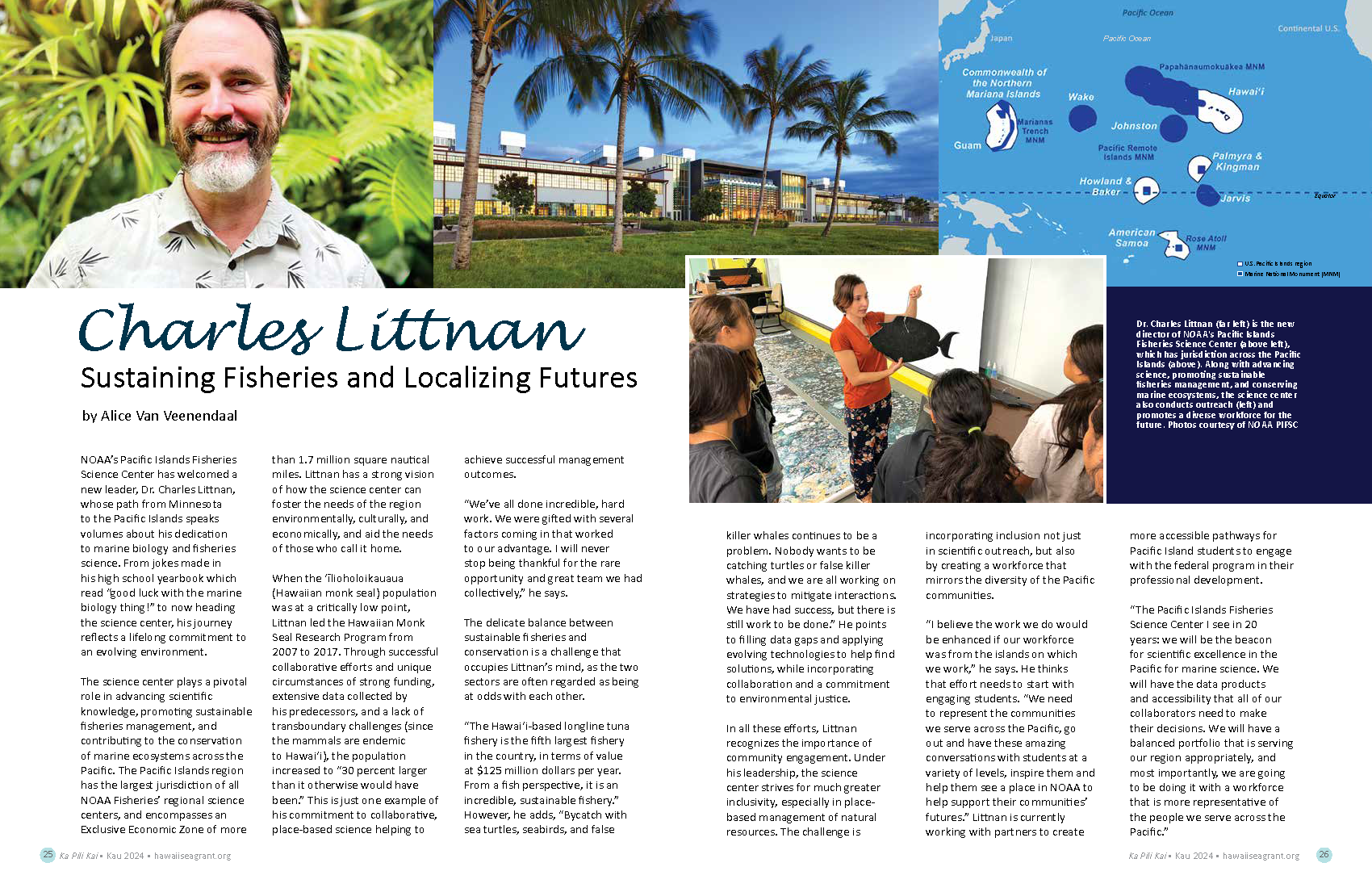

Charles Littnan: Sustaining Fisheries and Localizing Futures

by Alice Van VeenendaalNOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center has welcomed a new leader, Dr. Charles Littnan, whose path from Minnesota to the Pacific Islands speaks volumes about his dedication to marine biology and fisheries science. From jokes made in his high school yearbook which read “good luck with the marine biology thing!” to now heading the science center, his journey reflects a lifelong commitment to an evolving environment. The science center plays a pivotal role in advancing scientific knowledge, promoting sustainable fisheries management, and contributing to the conservation of marine ecosystems across the Pacific. The Pacific Islands region has

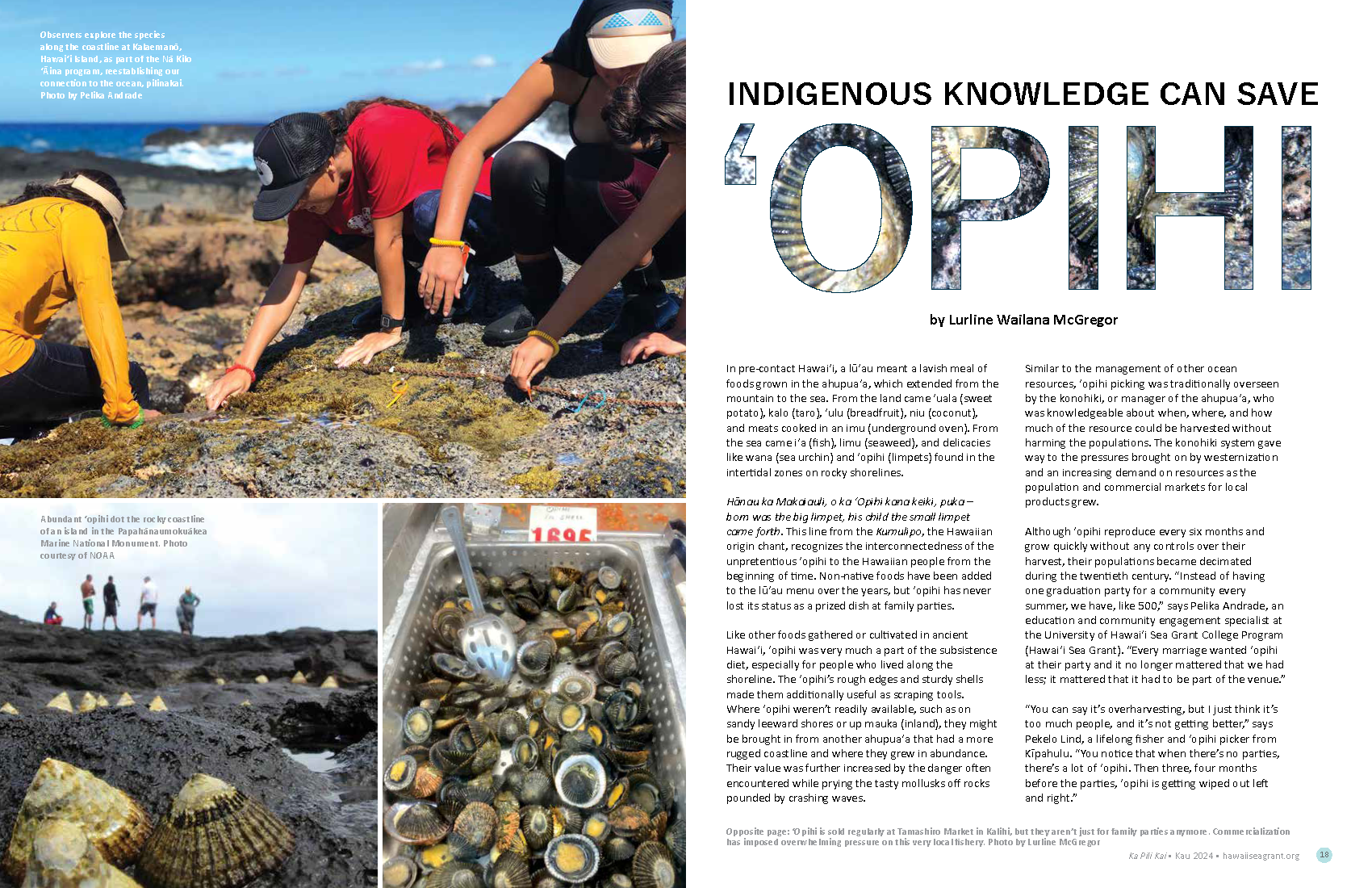

Indigenous Knowledge Can Save ʻOpihi

by Lurline Wailana McGregorIn pre-contact Hawaiʻi, a lūʻau meant a lavish meal of foods grown in the ahupuaʻa, which extended from the mountain to the sea. From the land came ʻuala (sweet potato), kalo (taro), ʻulu (breadfruit), niu (coconut), and meats cooked in an imu (underground oven). From the sea came iʻa (fish), limu (seaweed), and delicacies like wana (sea urchin) and ʻopihi (limpets) found in the intertidal zones on rocky shorelines. Hānau ka Makaiauli, o ka ʻOpihi kana keiki, puka – born was the big limpet, his child the small limpet came forth. This line from the Kumulipo, the

Eating Invasive Fishes

by Devin Reese Seafood has been a staple in Hawaiian diets for generations, since Polynesians settled the islands more than 1,000 years ago. Many communities across Hawai‘i fish locally and commercially, and restaurant menus feature fish that are both native and introduced to Hawaiian waters. However, things have shifted ecologically; native fish species are scarcer while species introduced from elsewhere have invaded habitats. “I’ve been diving all my life–40 years,” said Maui fisher Adam Wong. “There are many spots where I would target certain [native] fish, and now they’re filled with invasive fishes.” Species Introductions Adam Wong is also an

Navigating the Waves of Change in Pacific Fisheries

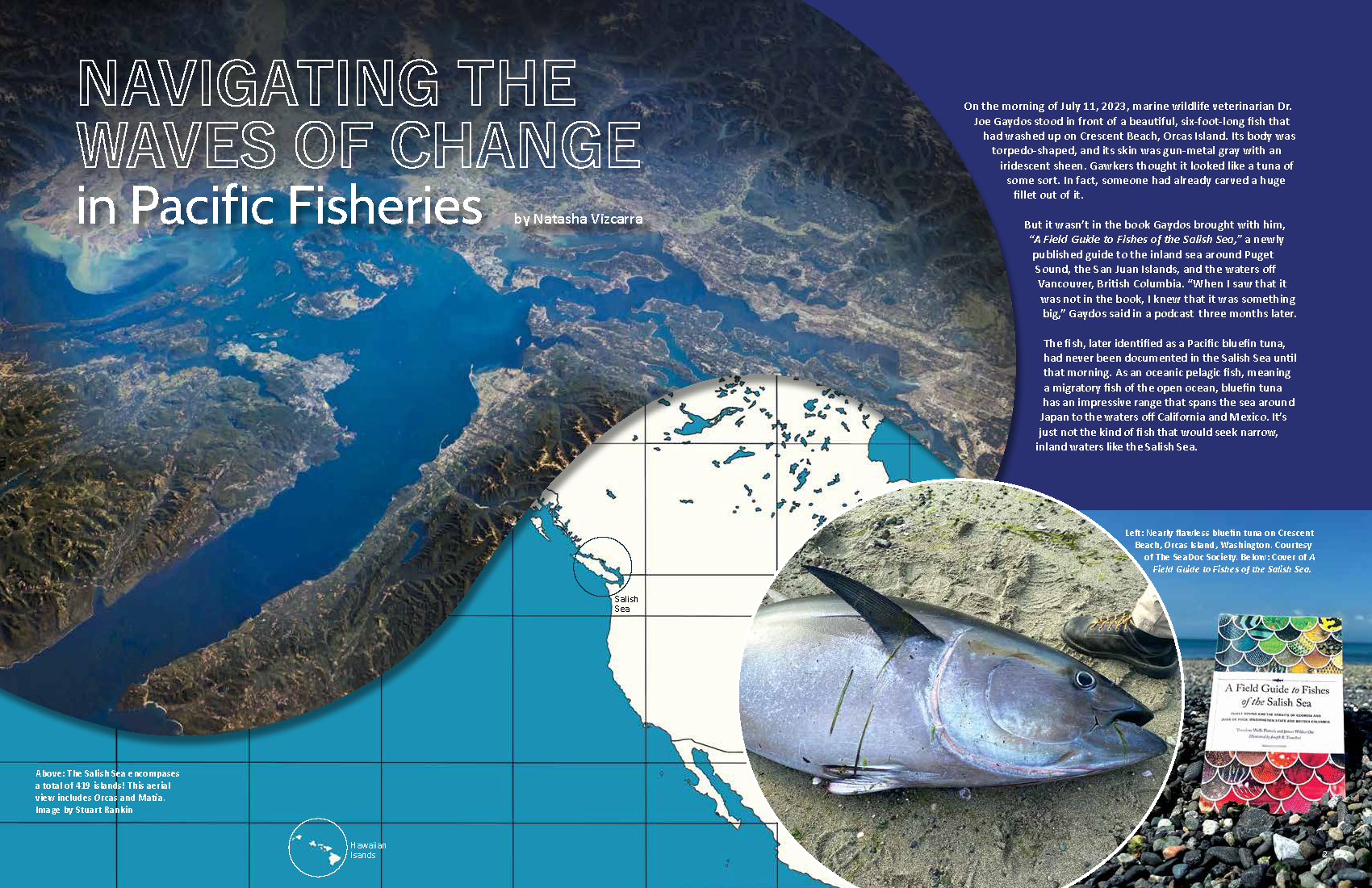

by Natasha VizcarraOn the morning of July 11, 2023, marine wildlife veterinarian Dr. Joe Gaydos stood in front of a beautiful, six-foot-long fish that had washed up on Crescent Beach, Orcas Island. Its body was torpedo-shaped, and its skin was gun-metal gray with an iridescent sheen. Gawkers thought it looked like a tuna of some sort. In fact, someone had already carved a huge fillet out of it. But it wasn’t in the book Gaydos brought with him, “A Field Guide to Fishes of the Salish Sea,” a newly published guide to the inland sea around Puget Sound, the San

Lawai‘a Pono Community-based Subsistence Fishing Areas

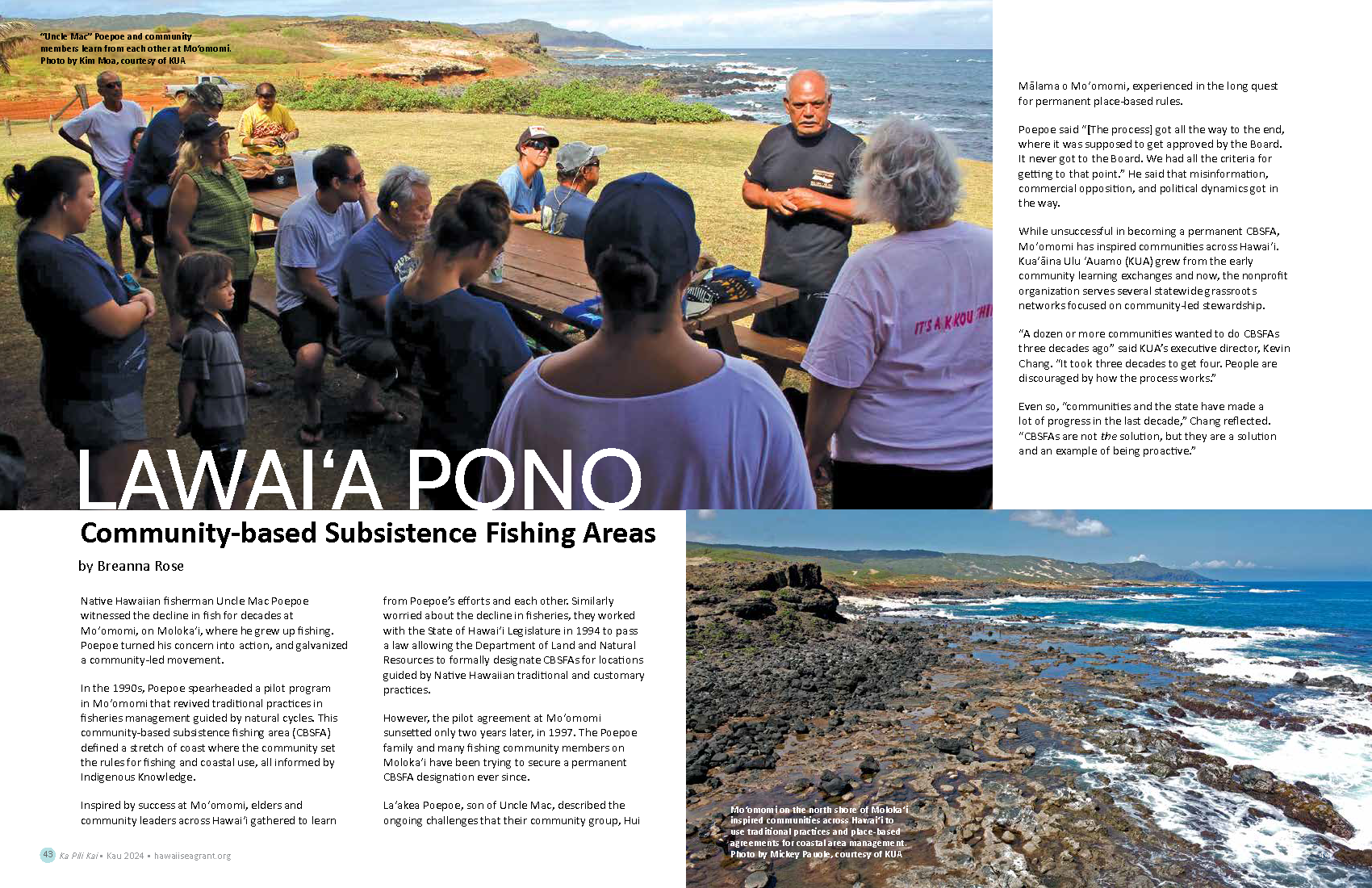

by Breanna RoseNative Hawaiian fisherman Uncle Mac Poepoe witnessed the decline in fish for decades at Moʻomomi, on Molokaʻi, where he grew up fishing. Poepoe turned his concern into action, and galvanized a community-led movement. In the 1990s, Poepoe spearheaded a pilot program in Moʻomomi that revived traditional practices in fisheries management guided by natural cycles. This community-based subsistence fishing area (CBSFA) defined a stretch of coast where the community set the rules for fishing and coastal use, all informed by Indigenous Knowledge. Inspired by success at Moʻomomi, elders and community leaders across Hawaiʻi gathered to learn from Poepoe’s efforts

License to Fish? Pros and Cons of a Potential Resident Non-Commercial Marine Fishing License

by Josh McDanielThe health of fisheries is vital to the marine environment, economy, and culture of Hawaiʻi. Subsistence fishing also plays an outsized role in food security for many who live in the state. In a recent NOAA survey of non-commercial fishers, 36 percent reported that their catch was an “extremely or very important part of their regular diet.” Given the range of pressures on fisheries, from habitat loss to overfishing, Hawaiʻi’s fisheries require well-informed management to ensure their sustainability for future generations. Yet, Hawaiʻi is the only coastal state that doesn’t require resident fishers to have a non-commercial marine

Seaweed Solutions for Feeding the Planet

by Cary DeringerTo increase future sustainable food production while reducing methane emissions, scientists are turning to the ocean, specifically seaweed, for answers. Food production needs will have to double to feed nearly ten billion people by 2050. However, production of protein-rich foods like meat and dairy poses dangers for the planet. For grazing livestock, digestion involves fermentation within their rumens—the first of four stomach chambers. This intestinal fermentation forms methane, a potent greenhouse gas released into the atmosphere every time a cow burps. But this seemingly harmless bodily output makes it up in volume. One cow’s burps amount to 220 pounds of methane annually. With one billion

Hope For The Seas

by Liz ColeyIf “developing solutions to monitor, protect, manage, and restore” ocean ecosystems sounds like a challenge the human species is unprepared to face, author Deborah Rowan Wright offers good news in Future Sea: How to Rescue and Protect the World’s Oceans. Her treatment of the subject is well-researched, informative, clear, and very readable, no matter one’s prior knowledge. Unlike many disheartening books about our warming, depleting, and plastic-filled seas, Future Sea offers a thrilling new perspective. Rowan Wright argues that international agreements are already in place to accomplish, in theory, what needs to be done. In their scope and intent, The Law of the Sea and many other international treaties apply protective rules and principles over 96 percent

Haunting the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

by Damond BenningfieldGhosts haunt the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. They glide in with the currents and tides, from all around the North Pacific Ocean. They destroy coral reefs and ensnare seals, sea turtles, and other endangered animals. They foul the beaches, present a hazard to boats, and cost millions of dollars to exorcise. These ghosts aren’t of the Halloween, supernatural, jump-out-and-shout- “boo” variety. Instead, they’re of human fishing gear, fishing nets lost or abandoned at sea that congregate in the islands. Known as ghost nets, they’re part of a growing problem not only in Hawaiʻi but around the world: marine debris, which affects life in the oceans and beyond. “It’s causing a

10 Years, 10 Challenges: Innovative Ocean Science Solutions in the Pacific

by Rayne SullivanWith worsening ocean health, the Pacific and much of the world are facing a multifront threat to heritage and culture, livelihoods, security, health, and ultimately their very existence. In Palau, it is said that when there is threat to one mesekuuk (surgeonfish), all rally together to meet the threat in force. In meeting this threat, the UN Ocean Decade rallies together people across domains and disciplines to develop impactful ocean science solutions for sustainable development centered on the interconnection between people and the ocean. This aim is further underpinned by the Decade’s vision: “the science we need for the ocean we want.” Nowhere is the central role of

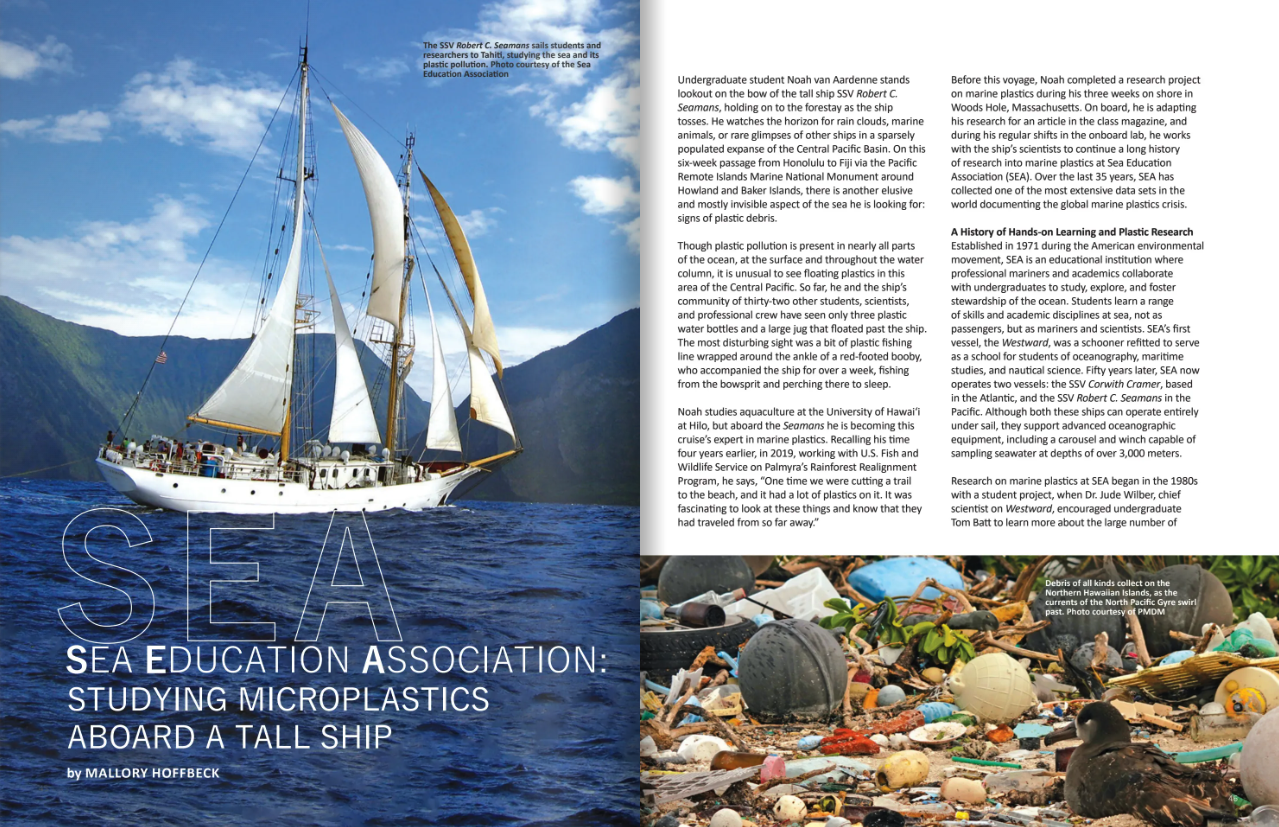

Sea Education Association: Studying Microplastics Aboard a Tall Ship

by Mallory HoffbeckUndergraduate student Noah van Aardenne stands lookout on the bow of the tall ship SSV Robert C. Seamans, holding on to the forestay as the ship tosses. He watches the horizon for rain clouds, marine animals, or rare glimpses of other ships in a sparsely populated expanse of the Central Pacific Basin. On this six-week passage from Honolulu to Fiji via the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument around Howland and Baker Islands, there is another elusive and mostly invisible aspect of the sea he is looking for: signs of plastic debris. Though plastic pollution is present in

Act Local, Act Global

by Lurline Wailana McGregorWhen the last of its four counties implemented laws to ban plastic bags from store checkouts in 2021, Hawaiʻi became the first in the nation with a full statewide ban. Since then, the City and County of Honolulu and Maui County have expanded their bans to include all takeout plastic and Styrofoam foodware, mandating two of the strongest plastic laws nationwide. While this is a significant effort in reducing the land-based plastic waste that often ends up on shorelines and in the ocean, it doesn’t address the estimated 15-20 tons of marine debris—mostly plastics—that piles up on

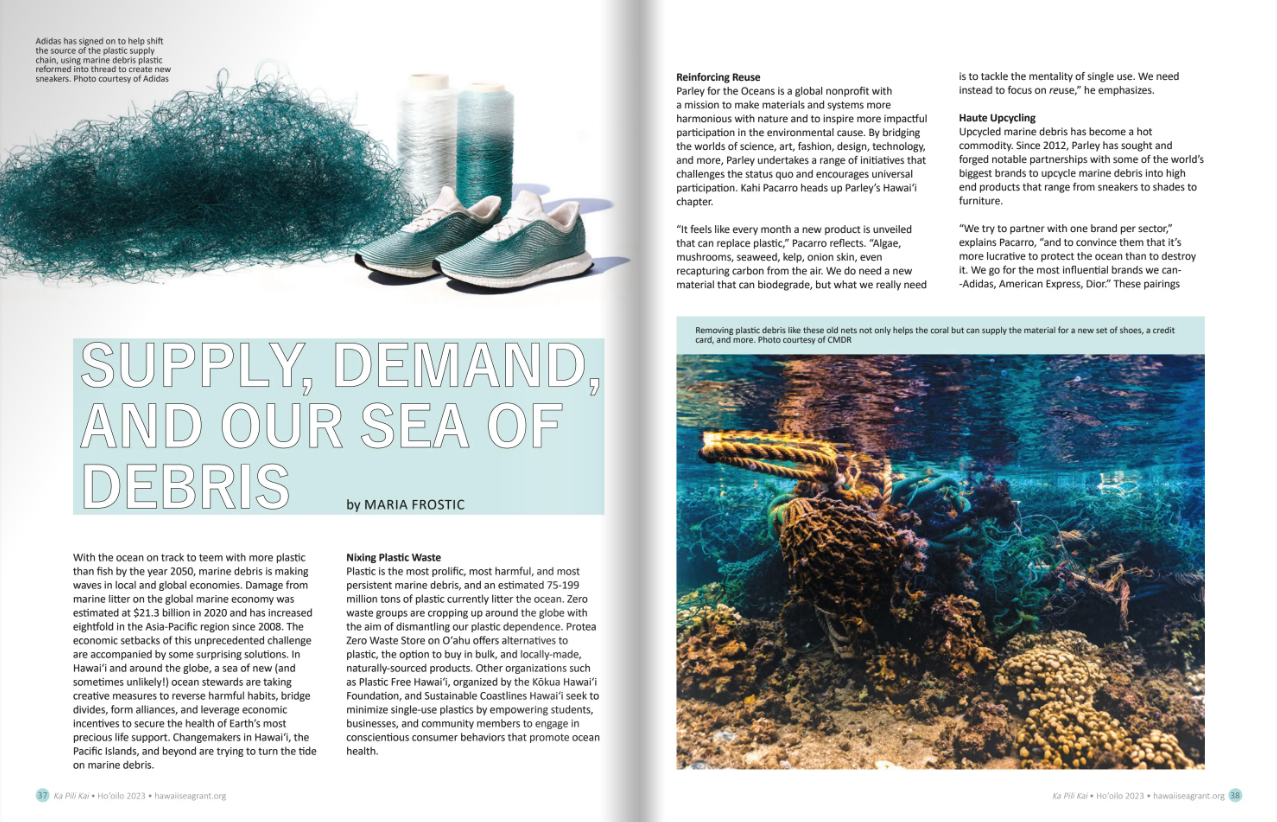

Supply, Demand, and our Sea of Debris

by MARIA FROSTICWith the ocean on track to teem with more plastic than fish by the year 2050, marine debris is making waves in local and global economies. Damage from marine litter on the global marine economy was estimated at $21.3 billion in 2020 and has increased eightfold in the Asia-Pacific region since 2008. The economic setbacks of this unprecedented challenge are accompanied by some surprising solutions. In Hawaiʻi and around the globe, a sea of new (and sometimes unlikely!) ocean stewards are taking creative measures to reverse harmful habits, bridge divides, form alliances, and leverage economic incentives to secure

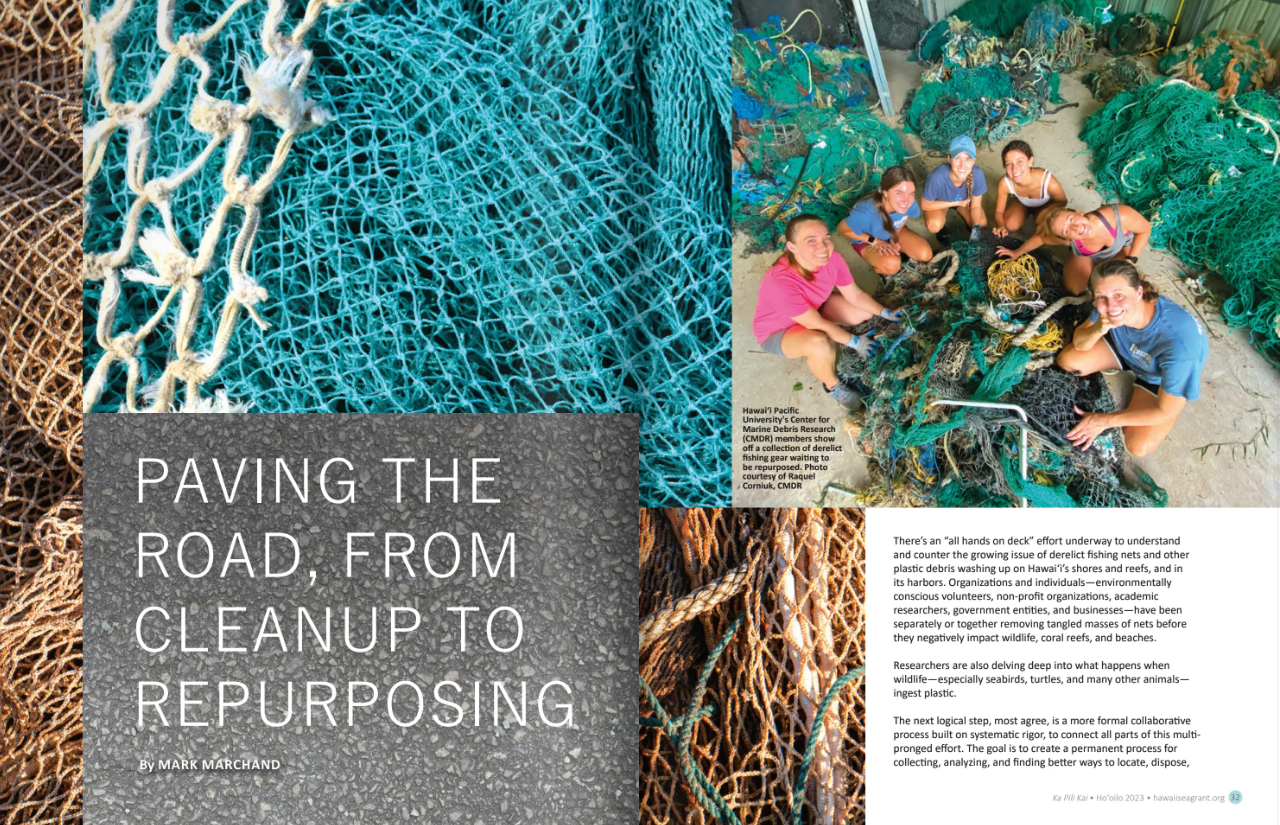

Paving the Road, from Cleanup to Repurposing

by Mark MarchandThere’s an “all hands on deck” effort underway to understand and counter the growing issue of derelict fishing nets and other plastic debris washing up on Hawaiʻi’s shores and reefs, and in its harbors. Organizations and individuals—environmentally conscious volunteers, non-profit organizations, academic researchers, government entities, and businesses—have been separately or together removing tangled masses of nets before they negatively impact wildlife, coral reefs, and beaches. Researchers are also delving deep into what happens when wildlife—especially seabirds, turtles, and many other animals— ingest plastic. The next logical step, most agree, is a more formal collaborative process built on systematic

Getting to the Bottom of U.S. Ocean Plastic Pollution: a Conversation with Leading Experts

by Tess JoosseThe United States uses and discards the most plastic in the world, churning out a whopping 42 million metric tons each year. Despite this distinction, as recently as 2020 the full scale of the U.S.’s contribution to ocean plastic pollution had never been comprehensively studied. In response, the U.S. Congress directed the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a groundbreaking committee of scientists, policy experts, economists, and other specialists to assess the magnitude of the problem. After an 18-month study, the committee published the first comprehensive report “Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean

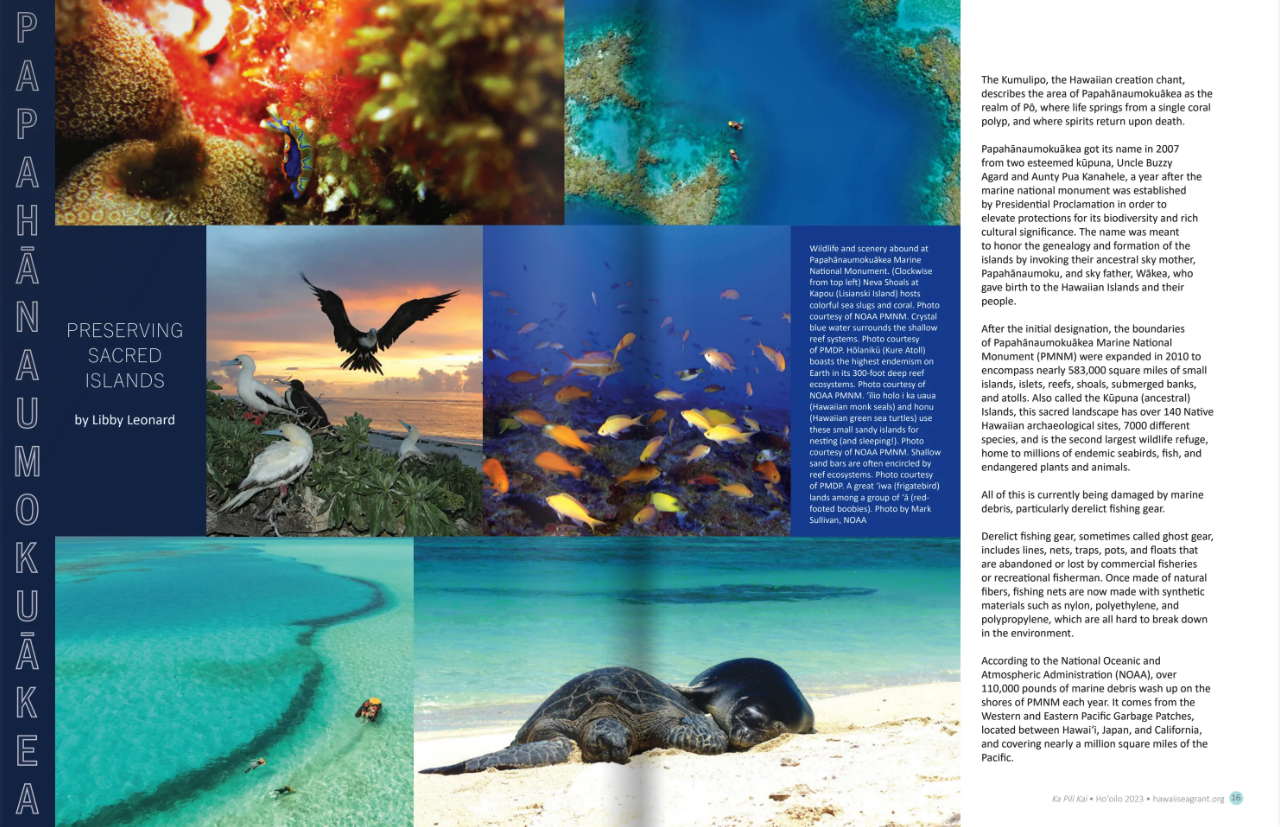

Preserving a Precious Place

by Libby LeonardThe Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant, describes the area of Papahānaumokuākea as the realm of Pō, where life springs from a single coral polyp, and where spirits return upon death. Papahānaumokuākea got its name in 2007 from two esteemed kūpuna, Uncle Buzzy Agard and Aunty Pua Kanahele, a year after the marine national monument was established by Presidential Proclamation in order to elevate protections for its biodiversity and rich cultural significance. The name was meant to honor the genealogy and formation of the islands by invoking their ancestral sky mother, Papahānaumoku, and sky father, Wākea, who gave birth

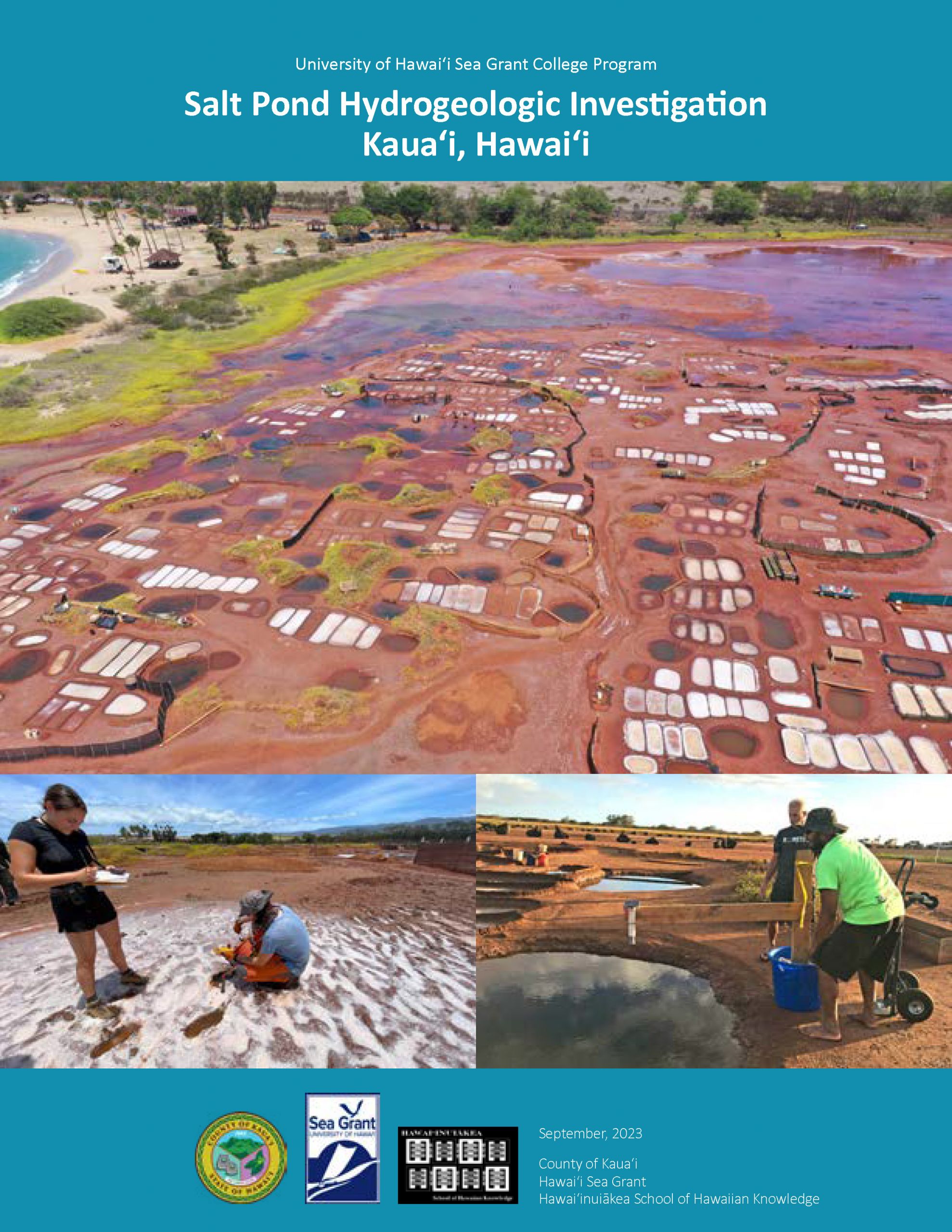

Salt Pond Hydrogeologic Investigation Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i

The Hawaiian cultural practice of making salt is one of Hawai‘i’s oldest traditions and Hanapēpē Salt Pond is one of the last places in all of Hawaiʻi that continues this tradition. The area and practice is highly treasured and protected by the salt makers as well as the larger community. Over the years this cultural practice has been threatened by increased marine and rainfall flooding (as well as user conflicts and nonpoint pollution) during the summer months, when ideal salt-making conditions require the Pond to be hot and dry. Throughout 2018-2022 a team of specialists, researchers, and practitioners were assembled

Hawaii Sea Grant Biennial Report 2020-2021

The University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program (Hawaiʻi Sea Grant) is organized into Centers of Excellence, a unique structure within the 34 university-based Sea Grant programs across the network. This allows the work of our faculty and staff to engage across our universities to bring approaches and solutions in service to communities throughout the region. The cover images depict the passion, commitment, and projects that are genuinely representative of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant and our expansive focus areas. Our program’s service is truly region-wide, with responsibilities spanning a geographic area greater than the continental United States. Hawaiʻi Sea Grant has

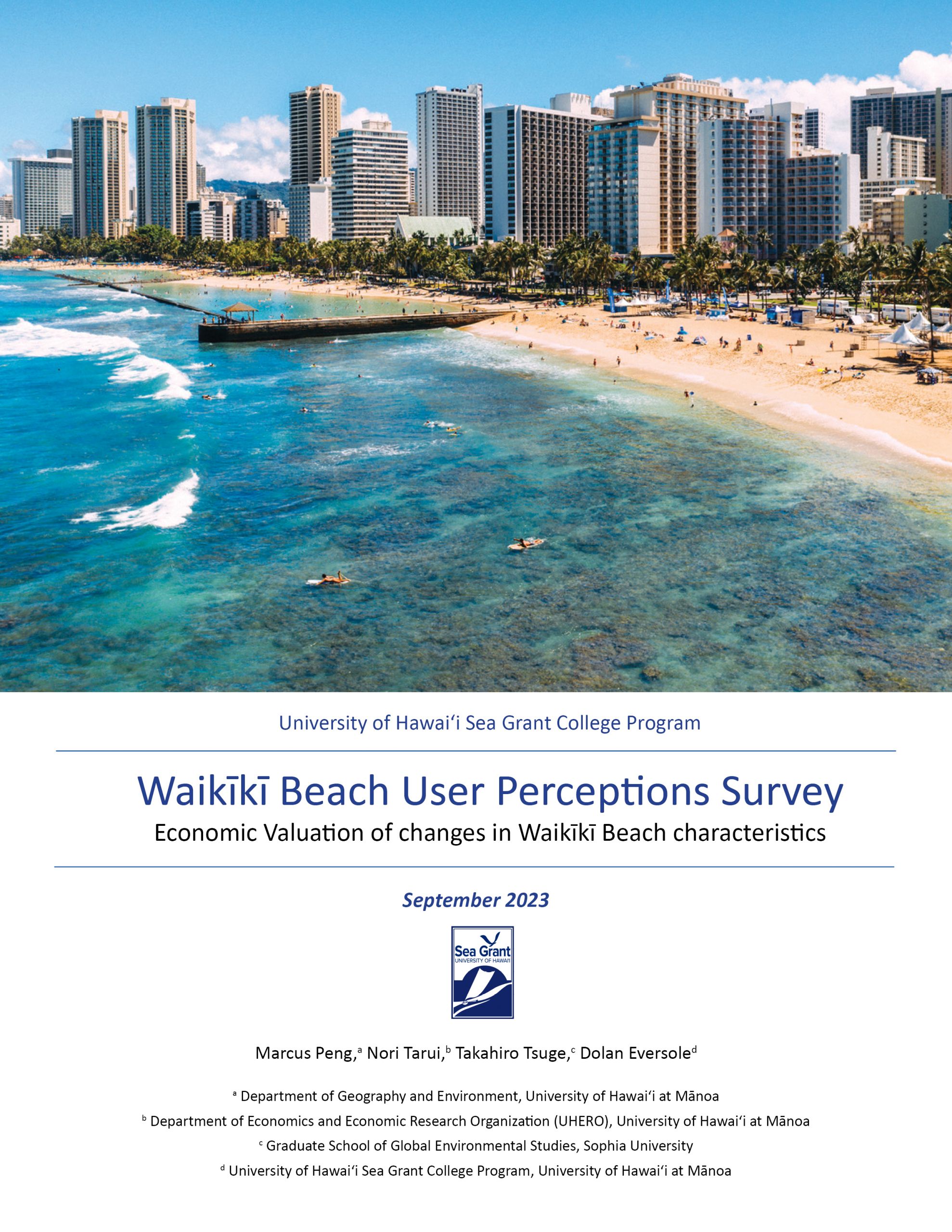

Economic Valuation of changes in Waikīkī Beach characteristics

Executive Summary Waikīkī Beach accounted for some $7.8 billion in visitor expenditures in 2019, representing 38% of total visitor expenditures statewide. Though the economic value of Waikīkī Beach is considered to be substantial, few studies have estimated the value in a comprehensive manner. Non-market valuation studies of natural resources are sorely lacking in Hawai‘i, the last major beach valuation on Oʻahu dates back to 1975 (Moncur, 1975). Based on an in-person survey in Waikīkī Beach conducted in November 2019-January 2020 with 398 respondents, we estimate beach user’s willingness to pay (WTP) for changes in beach width and water clarity as

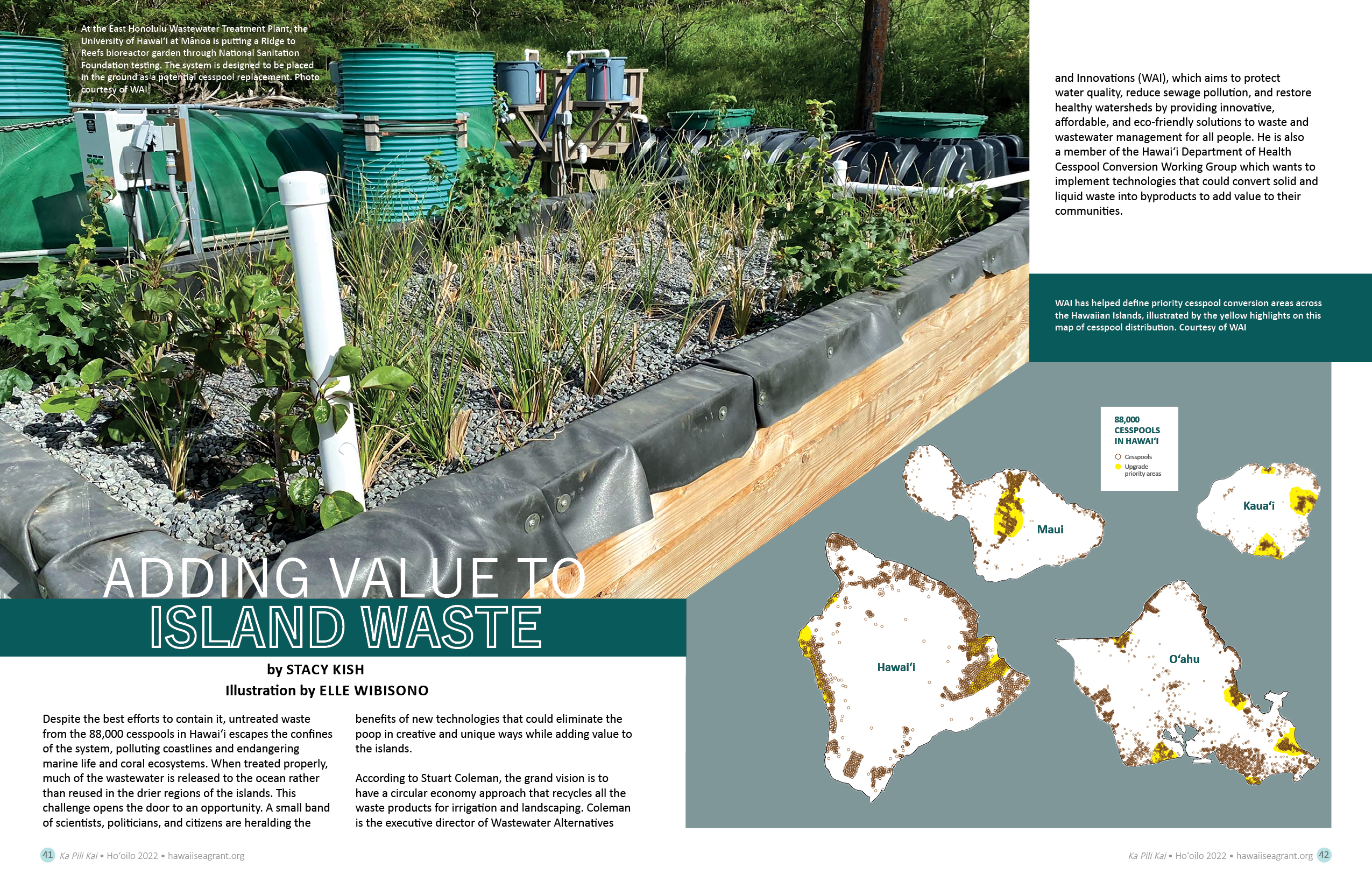

Adding Value to Island Waste

by Stacy KishDespite the best efforts to contain it, untreated waste from the 88,000 cesspools in Hawai‘i escapes the confines of the system, polluting coastlines and endangering marine life and coral ecosystems. When treated properly, much of the wastewater is released to the ocean rather than reused in the drier regions of the islands. This challenge opens the door to an opportunity. A small band of scientists, politicians, and citizens are heralding the benefits of new technologies that could eliminate the poop in creative and unique ways while adding value to the islands. According to Stuart Coleman, the grand vision

Restoring Water Quality and Bringing Back Coral Reef Ecosystems: Lessons from Kāneʻohe Bay

by Abbey SeitzOver the past century, wastewater, stormwater, and other pollutants from land and development have damaged our islands’ coastal ecosystems and nearshore waters. This degradation is due in part to the islands’ increasing urbanization coinciding with global warming. Given these immense challenges, many wonder, is there any hope of restoring these coastal areas? The recovery of Kāneʻohe Bay — from its sewage saturated waters and scum-covered reefs in the 1970’s to its now beautiful high coral cover condition — offers lessons in effective wastewater management and watershed remediation for coastal communities across the Pacific. To understand the revival of

Sewage in the seas

by Natasha VizcarraIt’s easy to get lost in the weeds finding out how to empty that portable 5-gallon toilet at the back of the boat. A simple Google search turns up a messy list of how-to videos, along with state and federal agency guidelines. However, Ed Underwood, chief of the Hawaiʻi Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation (DOBOR), simplifies it this way: “Either you go out three miles to dump untreated sewage, or pump it into a holding facility.” It’s a rule that’s true for all states with coastal areas. That leaves the boater and his portable toilet three options.

How Clean is Clean?

by Lurline Wailana McGregorBefore the Clean Water Act of 1972 became law, most of the agricultural wastewater and sewage from the Kaʻanapali coast on Maui, Hawai‘i was treated to remove only solids before being piped out into the ocean. After the wastewater started being injected into wells to comply with the new law, nearby residents started noticing algal blooms and destruction of the coral reefs in the waters along the once-healthy shoreline. That was the beginning of what would become decades of research by coral biologists, limu (seaweed) experts, and scientists who studied the exchange of groundwater between land and

Transforming the Ala Wai

by Josh McDanielFew of the millions of tourists who flock to the sparkling beaches of Waikīkī are aware that the area was once a vast estuary fed by three streams, Makiki, Mānoa, and Pālolo, which plunged from the steep slopes of the Ko‘olau Range down to the coast. The coastal marshes, loʻi kalo (flooded taro fields), and loko iʻa (fishponds) of Waikīkī sustained Native Hawaiians and later Chinese rice and duck farmers for centuries. The territorial government dug the Ala Wai Canal in Waikīkī during the 1920s to drain the wetlands. Construction of the canal allowed the development of Waikīkī

Making #2 a #1 Priority

by Kate FurbyStuart Coleman loves potty humor. But unlike the rest of us, he has a work excuse. And while not all of his puns are suitable for print journalism, suffice it to say that he approaches his work on sewage, wastewater, and cesspools with a lighthearted spirit. He has said a good poo pun helps keep him sane in this line of work. “It still makes me laugh that I’m dealing with wastewater. Sometimes I feel embarrassed about it. But it’s the thing that unites all humans and that we all have in common,” said Coleman. Learning to talk

Tackling Cesspool Conversion from Long Island to the Hawaiian Islands

by Shannon KelleherAs Hawai‘i prepares to carry out a massive overhaul of its numerous cesspools by 2050, the state finds itself in a quandary — waste treatment is expensive, and homeowners’ pockets only run so deep. “This is one of the biggest burdens the state is facing because it’s a $2 – 4 billion problem,” said Stuart Coleman, executive director and co-founder of Wastewater Alternatives and Innovations (WAI) and a member of the Hawaiʻi Department of Health’s Cesspool Conversion Working Group. Fortunately, this daunting task is one that communities across the U.S. have tackled before. Suffolk County, N.Y., which encompasses

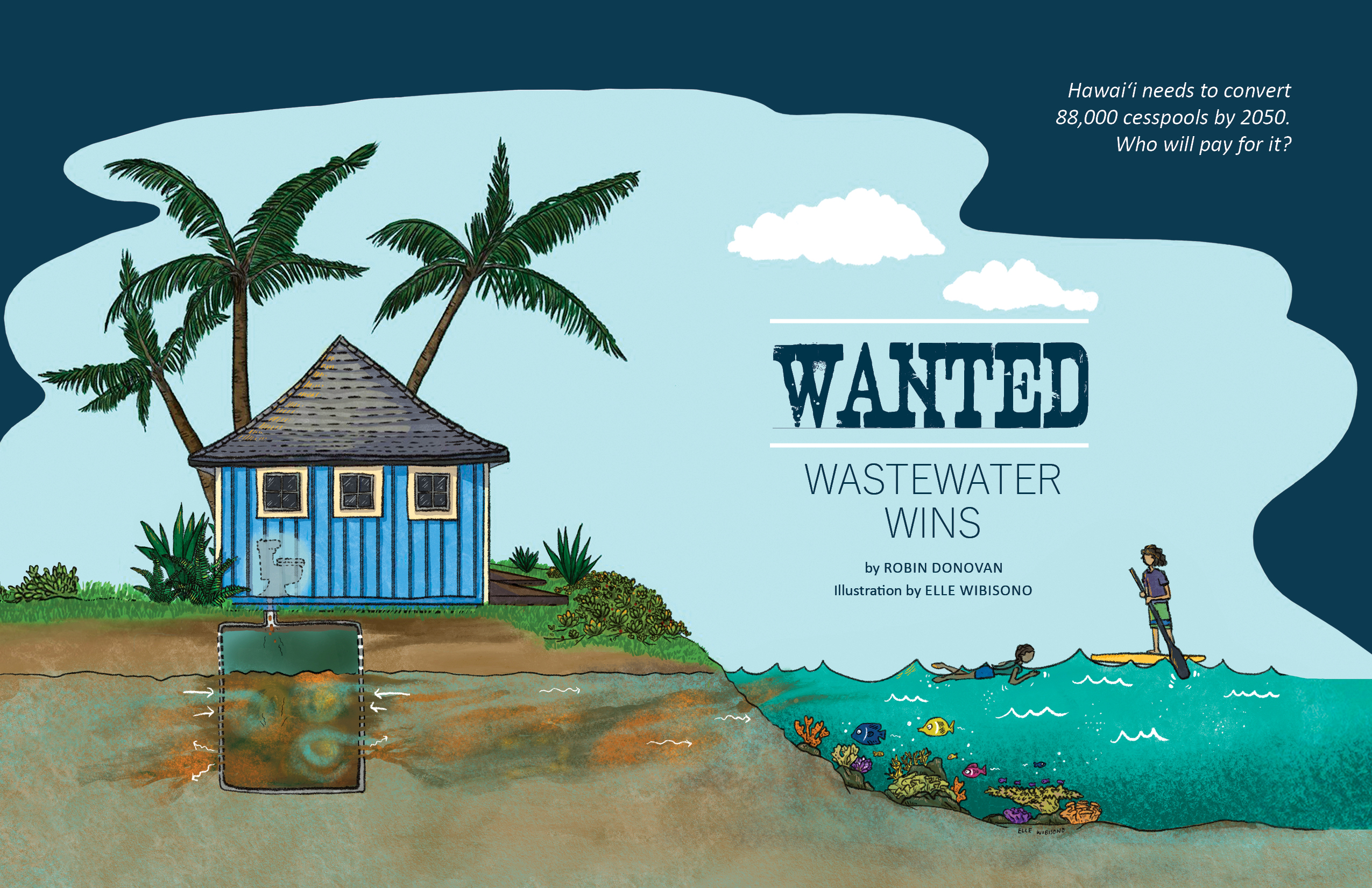

Wanted: Wastewater Wins

by Robin Donovan“It’s not a million-dollar question; it’s a billion-dollar question,” says Sina Pruder of Hawaiʻi’s cesspool conversion challenge. As an engineering program manager for the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Health’s (DOH) wastewater branch, Pruder has faced a daunting task since 2018: making recommendations to Hawaiʻi state legislators about how to tackle the mammoth effort of converting cesspools to more environment- and health-friendly alternatives like septic tanks and aerobic treatment systems. She’s part of the Hawaiʻi Cesspool Conversion Working Group. Cesspools are holes in the ground used to discharge untreated wastewater and sewage, which then travels through groundwater systems

Home Aquaponics – Your Next Passion?

by Liz ColeyIn 2011, author, educator, entrepreneur Sylvia Bernstein wrote AQUAPONIC GARDENING: A Step by Step Guide to Raising Vegetables and Fish Together to share her passion with the uninitiated. The book offers an engaging and practical deep dive into all the components of developing a working ecosystem of fish, plants, worms, bacteria, water, rocks, and air. This 250-page DIY is a quick read, offering the aquaponics-curious novice a springboard for deciding whether they are now enthusiastic, intrigued, or too daunted to take the plunge. Aquaponics practitioners, whether home growers or commercial farmers, have clearly found not only a hobby

IN THIS SECTION

Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Resources