The term “aquaculture” encompasses everything from restoring traditional fishponds to rearing seahorses for aquariums and reducing greenhouse gases with red algae. It’s a diverse field, and it’s booming: it’s the fastest growing sector of the agricultural industry worldwide, by a large margin. In Hawai‘i, the economic value of aquaculture doubled over the past decade, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. It now ranks fifth among the state’s agricultural products, below macadamia nuts and coffee, but above cattle ranching. In 2019, aquaculture companies in Hawai‘i reported $83.2 million in sales and 369 workers on the payroll.

For this swelling industry to truly benefit the people and communities of Hawai‘i, it needs an integrated local workforce. But how best to cultivate homegrown aquaculture experts? The answers are as diverse as the industry itself.

The Academic Route

The University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo (UH Hilo) offers the state’s only four-year aquaculture undergraduate degree. Students come here to wet their gills with a mix of classwork and experiential learning. In 2005, the university transformed an old wastewater treatment plant into the Pacific Aquaculture and Coastal Resources Center (PACRC), a research facility on nine oceanfront acres in Keaukaha. It aims to provide world-class mariculture programs and to support commercial aquaculture, fisheries, and conservation in Hawai‘i and beyond.

“We train and hire twenty to thirty students annually, plus hosting dozens of volunteers and interns,” says UH Hilo aquaculture professor Dr. Maria Haws.

At PACRC, students gain experience rearing larval fish, monitoring water conditions in the million-gallon tanks, and practicing sterile culture techniques in the laboratory. The opportunity to work with rare and beautiful reef fish is a big draw, says Haws. Students collect data on endemic species such as the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, Tinker’s butterflyfish, and Potter’s angelfish for the sustainable aquarium trade and conservation efforts. Marine food fish are another magnet. Local students who grew up eating āholehole, nabeta, and nenue are eager to learn how to propagate these precious cultural resources and provide sustenance for their communities.

Microalgae may not be as charismatic as a colorful wrasse or as delicious as a nabeta, but it’s the primary source of nutrition in the marine world. PACRC students supervise the center’s large-scale production of microalgae—a system of giant, liquid-filled bags that produces 4,000 liters a day. Another precious commodity inhabits the center’s half-million-gallon ponds: oyster spat. Haws worked with a Washington state oyster farmer for three years to figure out how to grow Pacific Northwest oysters in Hilo’s warmer climate. PACRC now partners with multiple local oyster hatcheries to export seed and larvae to the West Coast and to loko i‘a (Hawaiian fishponds).

“The skills you need to run an oyster farm are nothing you can learn from a book,” says Brian Koval, PACRC’s former hatchery manager. He trained students to culture algae, trigger spawning, and prepare shipments of larvae, and now works alongside several PACRC graduates at Hawaiian Shellfish, a two-acre oyster hatchery in Hawaiian Paradise Park. “A lot of students from the program were able to move into full-time or management positions in the industry,” he says. “They came with the skills that usually take years to learn on the job.”

Thanks to their top-notch training, UH Hilo’s aquaculture students have landed jobs nurturing native sea urchins for the Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources, and wrangling seahorses at Ocean Rider Seahorse Farm in Kona. “We treat our students as true professionals,” says Haws. “If there’s an emergency, we expect them to show up, whether it’s the middle of the night or a holiday. To be honest, it’s hard work. You have to have a passion for aquaculture.”

Other campuses around the state have waded into aquaculture education as well, on a smaller scale. Students at Windward Community College (WCC) on O‘ahu can earn credit studying Hawaiian aquaculture at Waikalua Loko Iʻa, a 400-year-old fishpond at the south end of Kāne‘ohe Bay. In this outdoor classroom, students experience firsthand the simple yet sophisticated design of the coastal pond and discuss what role loko iʻa can play in the future. They engage in centuries-old practices, including monitoring seasonal changes and capitalizing on spawning events.

At Waikalua Loko Iʻa, “they’re cultivating native limu (seaweed) and doing it in an aquaponics-type way with mullet and other Hawaiian fish species,” says Dr. David Krupp, dean of academic affairs at WCC. One of the program’s goals is to expand production to commercial scale and use the proceeds to fund the nonprofit and education programs. “The beauty of this,” says Krupp, “is having traditional Hawaiian aquaculture side by side with new high-tech aquaponics.”

The University of Hawai‘i Maui College and WCC both offer courses in aquaponics, a closed hydroponic farming system that uses fish waste to fertilize vegetables. Aquaponics students learn about water chemistry, fish anatomy, and food safety while designing and building systems for their homes.

“Small-scale backyard aquaculture shares many of the same principles as industry-scale commercial aquaculture,” says Krupp.

Eventually Krupp would like to see WCC play a role in Hawai‘i’s burgeoning algae industry. “There’s a whole slew of applications for algae culture—food supplements, phytoremediation, biofuels—but we’re not training people to do this yet,” he says. “It’s a unique niche that Windward could fill.”

To help fill that niche, Krupp can tap into a valuable resource: free curriculum courtesy of the Algae Technology Educational Consortium (ATEC). Dr. Ira “Ike” Levine runs the non-profit consortium and hails from the University of Southern Maine, but received his doctorate from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa). Levine reminisces about the days he spent restoring limu on Hawaiian reefs and working alongside world-class phycologists. “In the 70s, Hawai‘i was the epicenter for seaweed farming in the world,” he says. “We started ogo farming at Sand Island.”

Levine taught phycology, the study of algae, at UH Mānoa and Chaminade University on O‘ahu before relocating to the East Coast. Seven years ago, when the U.S. Department of Energy pumped $30 million into aquaculture, Levine asked, “Who’s going to train these people?” He landed the contract and launched ATEC, which now offers free educational tools for kindergarten through post-graduate students. “We’ve reached 140,000 students in 100 countries,” says Levine. “We have a series of classes that any school can adapt: laboratory lessons and lectures on algae biotechnology.”

ATEC created a custom five-course certification program for Santa Fe Community College. Students start out culturing algae in petri dishes, and progress to commercial harvesting and processing. After attending a series of online classes and one-week intensive labs, they earn the certification. Levine is keen to establish programs like this in Hawai‘i. “Our mission is to change people’s appreciation for algae and to develop the next generation of algal entrepreneurs.”

Putting a non-traditional degree into practice

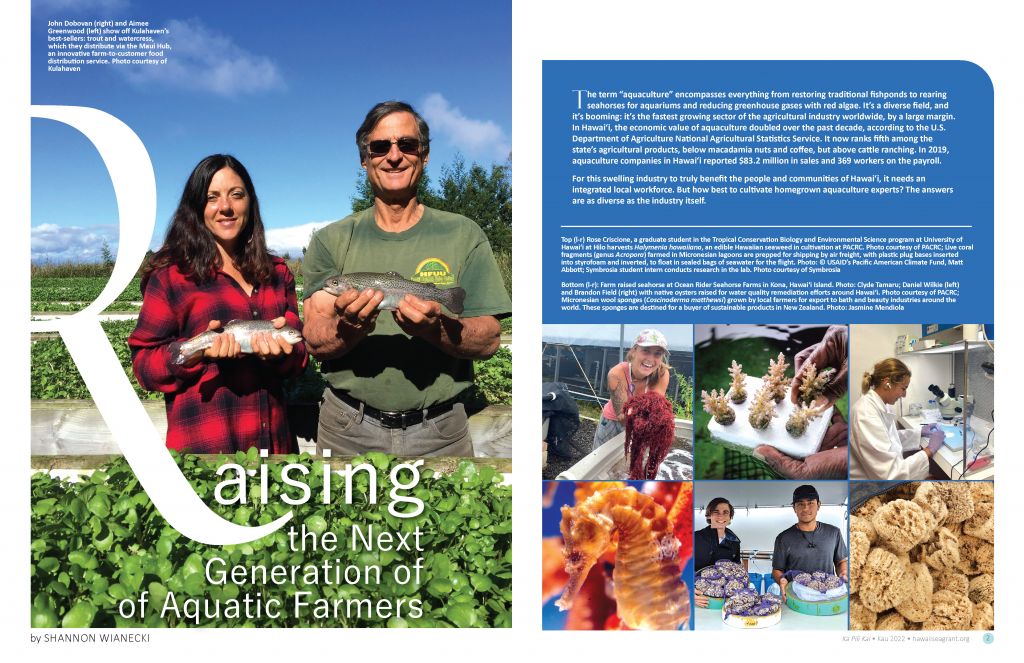

John Dobovan is an example of an aquaculture student who became an entrepreneur. He first learned about aquaponics in 2009 and felt so inspired that he went back to school at age 65. “I loved it,” he says. “I thrived.” He studied under Dr. Clyde Tamaru, a primary proponent of aquaponics during his time as a University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (Hawaiʻi Sea Grant) extension specialist. After raising tilapia in Waimānalo, Dobovan moved to Maui to pursue a degree in sustainable tropical agriculture and pioneer a new product: Hawai‘i-grown trout.

Kulahaven is Hawai‘i’s first commercial aquaponic trout farm. Dobovan spent five years perfecting his system, which produces a year-round supply of organic watercress and rainbow trout. “University of Hawai‘i Maui College has an outstanding agriculture department,” he says, “But nothing I learned truly prepared me for trout aquaponics. It was very tricky.”

Dobovan sells his trout exclusively to Mama’s Fish House—one of the state’s top restaurants—and the watercress to various markets on Maui and O‘ahu. “This whole thing has been a giant science experiment,” he says. “But it’s working well enough now that we’re feeding a lot of people. This little postage-stamp farm is capable of producing 2,500 pounds of food a month. We helped provide a portion of almost 200,000 meals last year—and that’s just off a third of an acre.”

Unfortunately, Dobovan’s tiny plot doesn’t generate enough income to cover overhead and staffing costs. He relies on help from volunteers and traveling farmers who exchange labor for room and board. In order to be fully profitable, Kulahaven needs to grow. Dobovan would like to expand to ten acres of land, with four acres dedicated to aquaponics and the rest for farm tours and education.

“I’m hopeful that we could generate hundreds of farms using the model we developed,” he says. He plans to provide prospective farmers with trout fingerlings and technical support. “We could offer help with sales, marketing, processing, and distribution. All the farmers would have to do is farm.” Internships are critical to his plan’s success. A six-month internship program would turn novices into new farmers. He feels that while classes are a good start to an aquaculture career, “hands-on experience helps tremendously. A combination is excellent.”

On the Job Training

As Hawai‘i’s academic institutions ramp up their resources, the aquaculture industry is taking up the slack by training workers on the job. Symbrosia is one of the newest, most innovative companies to move into the Hawai‘i Ocean Science & Technology Park in Kona on Hawaiʻi Island. The seaweed startup employs eight full-time technicians and multiple interns. “We’re really interested in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) interns,” says company founder Alexia Akbay. Since launching three years ago, Symbrosia has taken fifteen students under its wing from Hawai‘i high schools and colleges.

Symbrosia is an exciting workplace for aspiring aquaculturalists: it revolves around a new crop that hasn’t been grown commercially before, and has significant global application. Several years ago, self-described “climate optimist” Akbay learned that the red tropical macroalgae, Asparagopsis taxiformis, can reduce the methane emissions produced by livestock when added to cattle feed. Livestock burps account for ten percent of global greenhouse gas emissions; by incorporating A. taxiformis into cattle feed, Akbay hopes to decrease cows’ calamitous emissions by a whopping ninety percent.

Symbrosia is still in the discovery phase—generating less than a ton of algae per year—but what the company does produce goes to Hawai‘i cattle ranches. “We’re trying to make this a feasible product for local ranchers,” Akbay says.

Paid interns at Symbrosia join the research and development team where they get to tackle interesting challenges, such as how to streamline seaweed production and improve biosecurity. “We do a lot of data analysis in-house, too,” says Akbay. “Experimental design, testing different variables, background research…these are pretty core STEM thought processes that we give interns independence on.”

Akbay benefitted from experiential education herself. Symbrosia is a product of the Hatch accelerator program. “It’s a pretty awesome program—probably the top aquaculture accelerator,” says Akbay. “You’re in the cohort for a year, including three months on the ground with the Hatch team. They give you guidance and funding in exchange for a small amount of equity in your company.” Hatch helped place Symbrosia at the Hawai‘i Ocean Science & Technology Park, a unique outdoor demonstration site for emerging renewable energy, aquaculture, and other ocean-based sustainable technologies. “We ended up staying because we had access to free laboratory spaces for a year,” says Akbay. Akbay then paid the favor forward, offering valuable internship opportunities to local students.

Elsewhere in the Pacific

In the remote islands of Micronesia, Simon Ellis has been cultivating a community of ocean farmers. In 2005, he became the executive director of the Marine and Environmental Research Institute of Pohnpei (MERIP), a conservation initiative supported by many partners. Ellis and the MERIP team help Pohnpei farmers transition away from extractive practices to those that are sustainable and regenerative, like raising corals, sponges, and ornamental clams. Farming these types of products for the aquarium trade helps relieve pressure off wild populations.

“Essentially, what we do is help people to set up small farm plots and sell their products,” he says. MERIP trains farmers to grow sustainable marine products and then helps market them internationally. “Today we have a product line of more than 30 live corals for sale,” says Ellis. “We partner up with wholesalers. It doesn’t bring in a massive amount of money, but it’s enough to replace the $1,000-a-year per capita income.” Around fifty small family farms presently produce four to five thousand live corals per month for the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

The institute is experimenting with new products such as edible giant clams and rabbitfish, but any new venture requires years of research and development. MERIP recruits local fishermen to help find the fish and identify their habits, local restaurant owners to promote the new product, and community leaders to support the industry. Ellis has learned that marine aquaculture is an extremely specific endeavor. It needs to work within the natural ecosystem of the place, while also meeting the needs of the community.

“Everything is place-based,” Ellis says. “The things we develop may be relevant to other parts of the Pacific, but the whole equation is: what’s already there that you can work with, and can it be used to sustain people?”

Bridging the Gap

In 2021, the Hawai‘i Aquaculture Collaborative (HAC) formed to bridge some of the gaps between industry, academia, and other potential partners. “To start, we just wanted to hear from the industry itself,” says Dr. Kai Fox, an aquaculture extension specialist with Hawaiʻi Sea Grant who facilitates the HAC. When they invited local industry leaders to identify priority areas, workforce development was in the top three.

The HAC recognized both the need for skilled workers and the potential for aquaculture to provide stable employment, high salaries, and hands-on, interesting work. “Based on what we’ve been hearing,” says Fox, “there are close to 100 jobs in the state that aren’t filled right now. One farm in Kohala has around 30 openings.” While most of these are entry level—scrubbing tanks and basic animal husbandry for under $20 per hour—others require specialized training.

Fox’s colleague Cherie Kauahi, also a Hawai‘i Sea Grant faculty member in aquaculture extension, conducted a six-month study of the existing workforce, during which she queried three different groups: fishermen, Hawaiian fishpond practitioners, and commercial aquaculturalists. When she inquired about their education and what skills they needed to do their work, most, like Dobovan, cited the importance of hands-on experience and apprenticeships. “We’re finding that a four-year degree is not always required,” says Kauahi. After tallying the skillsets from the workforce study, she also notes that commercial aquaculture could learn a lot from traditional Hawaiian fishpond practices. Kauahi says, “Loko i‘a bring people together and give them a sense of identity, through their culture and practice.”

While the paths to satisfying employment in Hawai‘i’s aquaculture industry are varied, one thing is certain: we have more than enough local expertise to lead the way.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE