To increase future sustainable food production while reducing methane emissions, scientists are turning to the ocean, specifically seaweed, for answers.

Food production needs will have to double to feed nearly ten billion people by 2050. However, production of protein-rich foods like meat and dairy poses dangers for the planet.

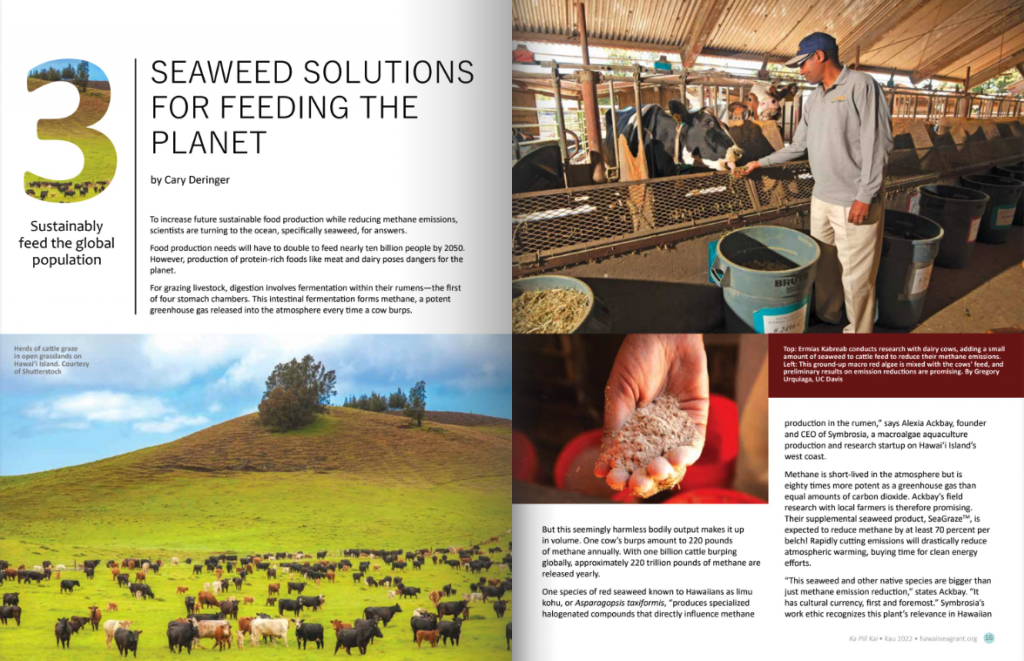

For grazing livestock, digestion involves fermentation within their rumens—the first of four stomach chambers. This intestinal fermentation forms methane, a potent greenhouse gas released into the atmosphere every time a cow burps.

But this seemingly harmless bodily output makes it up in volume. One cow’s burps amount to 220 pounds of methane annually. With one billion cattle burping globally, approximately 220 trillion pounds of methane are released yearly.

One species of red seaweed known to Hawaiians as limu kohu, or Asparagopsis taxiformis, “produces specialized halogenated compounds that directly influence methane production in the rumen,” says Alexia Ackbay, founder and CEO of Symbrosia, a macroalgae aquaculture production and research startup on Hawaiʻi Island’s west coast.

Methane is short-lived in the atmosphere but is eighty times more potent as a greenhouse gas than equal amounts of carbon dioxide. Ackbay’s field research with local farmers is therefore promising. Their supplemental seaweed product, SeaGrazeTM, is expected to reduce methane by at least 70 percent per belch! Rapidly cutting emissions will drastically reduce atmospheric warming, buying time for clean energy efforts.

“This seaweed and other native species are bigger than just methane emission reduction,” states Ackbay. “It has cultural currency, first and foremost.” Symbrosia’s work ethic recognizes this plant’s relevance in Hawaiian culture, aiding their understanding of the species and ensuring that their efforts remain pono (correct). “Not taking the first sample seen, or the largest, or more than 50 percent, and not harvesting roots,” Ackbay explains, “is how Indigenous practices and thought processes are incorporated. The continuity of the resource for the next seven generations is kept in mind.”

Todd Low, the aquaculture and livestock support services manager with the Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture, agrees. He is promoting such restorative aquaculture practices to support the ecosystem and economic services while improving ocean health. “That’s the push this year,” says Low. “Get funding to examine Indigenous seaweed, replenish nearshore stocks, and expand offshore growth potential.”

Seaweed aquaculture is globally relevant for producing protein-rich foods, and this growing industry is driven by scientific development and innovation. “We’ve developed, through natural selection and breeding, strains with advantageous traits for both aquacultural production and farm use,” states Ackbay. “There’s no genetic modification.”

Cows are proof. “Each animal is 8-10 times more productive,” says Dr. Ermias Kebreab at UC Davis’ Department of Animal Science. Reducing livestock numbers, while increasing food production, benefits humans and the planet. Combining restorative aquaculture practices with zero ocean impact brings those benefits full circle. “Only three ounces a day,” says Dr. Kebreab, are necessary to see these positive results.

Symbrosia’s innovative macroalgae biotechnology improves production in photobioreactors—enclosed systems kept at controlled environmental conditions. “We work closely with coastal organizations and cultural practitioners,” says Ackbay.

Seaweed solutions to increase global food production, foster food sovereignty for Hawai‘i, and build climate resilience—that’s something worth ruminating on!

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE