“It’s not a million-dollar question; it’s a billion-dollar question,” says Sina Pruder of Hawaiʻi’s cesspool conversion challenge. As an engineering program manager for the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Health’s (DOH) wastewater branch, Pruder has faced a daunting task since 2018: making recommendations to Hawaiʻi state legislators about how to tackle the mammoth effort of converting cesspools to more environment- and health-friendly alternatives like septic tanks and aerobic treatment systems. She’s part of the Hawaiʻi Cesspool Conversion Working Group.

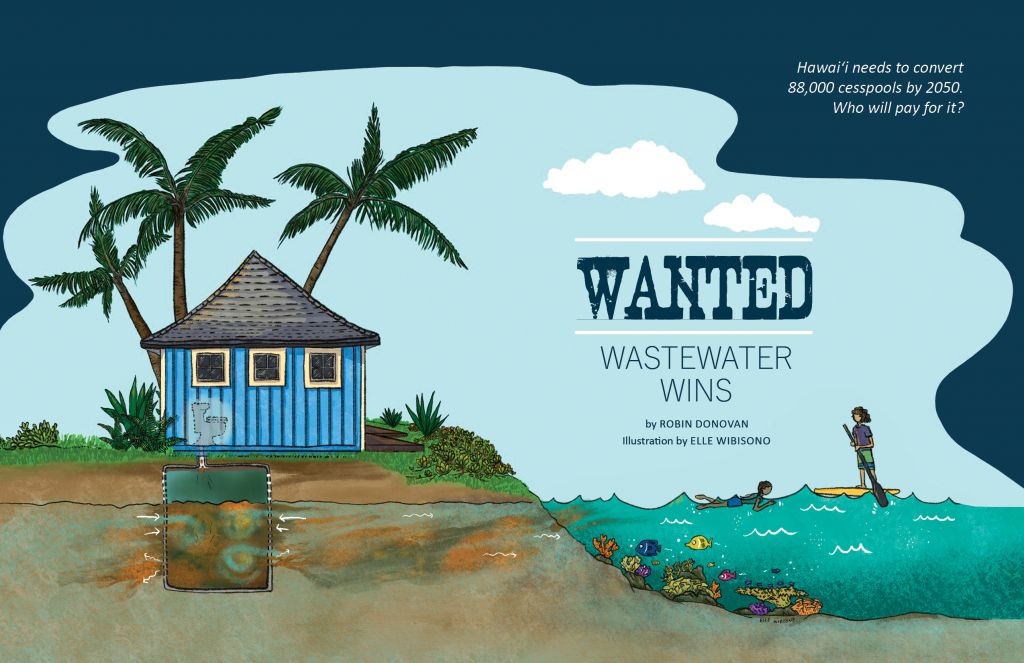

Cesspools are holes in the ground used to discharge untreated wastewater and sewage, which then travels through groundwater systems into the ocean. Raw sewage from cesspools contains pathogens that can cause a host of infections in swimmers, surfers, and other water users. It also contains excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus that can contaminate groundwater and nearby well-water, as well as damage ocean ecosystems. Coral reefs and limu (seaweed), already subject to warming ocean temperatures and an increase in other pollutants, are stressed, if not killed, through the overgrowth of invasive algae that thrive on the introduced nutrients.

Challenges in Hawaiʻi and across the Pacific

As population levels rise, sewage discharge increases too, creating a largely invisible but looming problem for the state, its residents, and the visitor economy. New regulations passed in 2017 require that all Hawaiʻi cesspools be “upgraded, converted, or closed” by 2050. But the state faces billions of dollars of costs associated with remediating cesspools one by one. Some taxpayers took advantage of a $10,000 credit, offered as part of Act 125 which established the 2050 deadline, but the credit expired in 2020.

“Island communities are really on the front lines. They’re in a crisis. They’re facing challenges, things like drought, contaminated water supplies, rising sea levels,” says Michael Mezzacapo, a former extension specialist with the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UHM) Water Resources Research Center (WRRC) and Sea Grant College Program, and now with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). He joins Pruder on the Cesspool Conversion Working Group, which will make its official recommendations to legislators before winding down at the end of 2022.

Hawaiʻi isn’t the only place facing cesspool problems. For low-lying Pacific Islands coping with sea-level rise, the issues are intensified, and even a high island like American Samoa is challenged by an increasing demand to manage its wastewater. Dr. Chris Shuler, a surface and groundwater hydrologist with WRRC, used geospatial analyses to study wastewater management on the island.

“In general, they’re not really installing new houses with cesspools, but there’s probably some that are still going in,” says Shuler. Similar to Hawaiʻi, the issue of cesspool conversion in American Samoa comes down to funding shortages.

Some Samoan homeowners benefitted from funding set aside by the EPA, Region 9, which partnered with the American Samoa Power Authority (ASPA) to address water quality issues by relocating contaminated wells, adding sewer infrastructure, and converting some cesspools to septic systems. The wastewater treatment utility identified top targets for replacement, and the funding covered cesspool removal and pump-out, plus septic installation. According to an EPA report, 194 cesspools were converted between 2006 and 2017, with roughly 200 more to go.

Digging deep to help

In Hawaiʻi, 53 million gallons of sewage are released per day from the state’s 88,000 cesspools, but the problem, like the waste itself, remains buried. “It’s more like a drip, drip, drip, versus the jarring image of the river on fire or a pipe jetting into the ocean and spilling sewage,” Mezzacapo says.

Even now, conditions have to be just right for beach visitors to notice direct effects and impacts like sewage smells near beaches that wouldn’t necessarily be reported to the DOH, making them hard to track. Still, levels of Enterococcus bacteria, an indicator of fecal contamination, exceed safe levels at varying frequencies, and some beaches and waterways throughout Hawaiʻi that are regularly used by the public consistently exceed safe levels. The Surfrider Foundation’s Blue Water Task Force, which partners with a marine lab at UHM, posts regularly updated bacterial levels for Hawaiian beaches, as well as for coastlines across North and Central America.

Pruder says her department wants to help and is looking into setting aside $5 million to do so each year. Using pass-through loan agreements, the money would be funneled to counties for cesspool upgrades. However, Pruder estimates the true cost to convert all 88,000 cesspools is closer to $2 billion. She realizes that homeowners probably won’t be able to foot the bill either, so the Cesspool Conversion Working Group hired a consultant to explore the affordability of conversions.

“The report was kind of depressing,” she says. “About 95 percent of residents couldn’t afford the upgrade because you needed to have a household income of $125,000 or more.” Because these conversions cost $20,000 to $50,000, Pruder doesn’t blame homeowners for delays in conversions, since many are largely unaware of the problem or simply unable to address it without grants or tax credits.

Infrastructure challenges

Cesspools became popular because they are low maintenance and circumvent the need for costly infrastructure, like wastewater treatment plants and sewage lines. On Oʻahu, the majority of homes are connected to a sewer system. Elsewhere, Pruder says, low population density has made it impossible for wastewater treatment utilities to recoup the expenses of extending sewer lines to small communities.

Factors like distance from a residence to the treatment facility can require costly equipment like pump stations or grinders. Monthly utility fees from homeowners have to cover future repairs, but there aren’t enough residents to cover those fees. Mezzacapo points to Hilo, where a failing, outdated wastewater treatment system needs millions in urgent repairs that the county can’t afford.

“If you charge too much, then no one can afford it. If you charge too little, then it doesn’t get maintained,” he says. So, while some new wastewater treatment systems are in the works, such as on Maui, Pruder expects that 90 percent of existing cesspools will need to be converted using other technologies.

New methods for safer septic

Septic tanks are a step up, but only that, according to Stuart Coleman, executive director of the nonprofit Wastewater Alternatives & Innovations (WAI). “You’re going to go from the worst system to a very, very mediocre system that still has all these nutrients [released],” he says, pointing to dilapidated systems along the U.S. East Coast that are now in need of replacement.

However, Pruder points out that new options for septic leach fields are more environmentally friendly. Passive systems that have already been used on the U.S. East Coast feature modified leach fields filled with wood chips and sand. These materials reduce the nitrates released into groundwater without requiring the electricity and additional maintenance of Aerobic Treatment Units, or ATUs. This helps keep drinking water contaminant levels within established safe levels and can prevent algae blooms that damage coral reefs.

Still, “climate change will exacerbate the issue,” Mezzacapo says. “We need to think about long-term, sustainable, and resilient solutions.” Even if a cesspool is replaced with a septic system, sea-level rise is already raising groundwater levels in many coastal zones, impeding the efficiency of these systems. Septic tank lines have holes through which liquids escape into a leach field, which helps remove contaminants and impurities from the wastewater draining from the tank. A rise in groundwater levels means that the septic system’s leach field can’t treat the wastewater adequately before pollutants enter the water table, requiring a different method to be effective.

Currently, there’s “no real enforcement” of septic maintenance and function, says Juanita Reyher-Colon of the Hawaiʻi Rural Water Association, whose members include wastewater utility workers. “Who’s actually paying attention to communities that have these systems, to check that they’re maintaining their systems, or even just doing an annual checkup of the functionality of the systems?” she asks. “There’s nothing really in place right now.”

High-tech solutions for every homeowner

For island properties at risk of erosion and rising groundwater tables, factors like lot size, groundwater depth, and distance to the coastline impact which wastewater alternative treatment methods should be used. A range of onsite treatment systems remove nitrogen and are typically better for the environment than a septic system. Cluster systems, used to manage wastewater from a group of adjoining properties, are another option, if one that threatens some administrative headaches. They require neighbors to split costs equitably, maintain systems together, and establish easements for installing and accessing the systems.

“[The best system is] very site-specific. So, something that might work on the Kona Coast might not be good for the Hilo coast,” Mezzacapo says. ATUs are still the gold standard, removing nitrogen better than septic systems. They use both non-oxygen and oxygen-loving bacteria to break down waste and remove nutrients.

Through WAI, Coleman has partnered with a handful of manufacturers, helping promote newer technologies that he says are more effective than cesspools or septic systems at preventing groundwater contamination by treating waste in-place. These companies include the Cinderella Eco Group whose waterless toilets incinerate waste and turn it into pathogen-free and odorless ash. Another option is Eljen’s passive filtration system that creates an enhanced leach field to reduce nitrogen without pumps or increased utility costs. A company named Orenco even offers sanitation as a service for a monthly fee, installing pressurized sewer systems that collect all the household waste and pump only the liquids through flexible sewer lines that are inexpensive to install compared to traditional utilities.

Despite the difficulties of sharing high-tech solutions to a problem that many Hawaiʻi residents barely recognize, Coleman hopes WAI’s social entrepreneurship model will offer cesspool alternatives that more people can actually afford. “Our town hall meetings are well-attended, and people are excited,” he says.

Wailua homeowners Robert and Magenta Zelkovsky replaced their cesspool with a Cinderella combination system, installing an incinerating toilet and greywater management system. The couple’s home is a test case in Hawaiʻi for the new technology. Robert Zelkovsky says it was hard to switch systems after 70 years of flushing, but he’s happy that he’s no longer adding to the cesspool problem, particularly because he learned that the former cesspool was just five feet above the groundwater beneath the couple’s home.

“I think we’re definitely the first in the country to have incinerating working toilets in the house,” he says. His social media posts about the new toilet have aroused both humor and curiosity from friends and neighbors.

Working Group recommendations

Not every cesspool is equally damaging, but “all cesspools contribute some impact to the environment,” Mezzacapo says. The Cesspool Conversion Working Group’s recommendations include bumping up the deadline for high priority cesspools, those with the most potential to release damaging effluent into groundwater and the ocean. Each cesspool will be labeled as priority one, two, or three through a statewide tool Mezzacapo and Shuler co-developed. It incorporates 15 factors, including social, environmental, and health factors, to determine which cesspools are the most impactful. Priority one cesspools have the highest risk of human impact or drain to sensitive waters. Priority two cesspools threaten to impact drinking water, and priority three cesspools have lesser potential impacts.

Mezzacapo and the UHM team are also developing a web-based tool that will allow homeowners to quickly determine which priority area they live in. The working group hopes legislators will be willing to push up the deadline for the most damaging cesspools to as soon as 2030, Pruder says. So far “we haven’t seen a whole lot of upgrades because the 2050 deadline seems so far away.” But she acknowledges that this could be controversial among homeowners, and Mezzacapo agrees.

“It’s almost 100 percent likely that our tool, the priority zones, will be used as the basis to potentially say that priority one zones should be upgraded first, with grants offered to low-income homeowners in priority one zones,” he says.

Mezzacapo, Shuler, and Melanie Lander from Hawai‘i Sea Grant are also planning educational outreach to share how cesspools pollute groundwater and oceans, why the tool was developed, and how it will be used. “Just because you’re in priority one doesn’t mean you should be upset about it,” Mezzacapo says.

New legislation offers hope

A recently passed bill, H.B. 2195, will financially assist low- to moderate-income Hawaiʻi households with failing cesspools, in other words those classified as priority one, two, or three. The program will provide grants up to $20,000 on a sliding scale based on homeowners’ gross income, as reported on their federal taxes. A total of $5 million is earmarked for these grants.

And while the prioritization tool will be available to the DOH almost immediately, finalizing an official state plan to convert all of Hawaiʻi’s cesspools is still years away. “There are going to be some very contentious issues that arise,” Mezzacapo says, and the first debates may well be over the very tool he created, as homeowners face new timelines for urgent cesspool conversions.

Some Hawaiʻi residents stand to benefit from new jobs created by demand for cesspool conversions in the coming years. Coleman has partnered with local community colleges to develop training programs for five types of wastewater workers including individual wastewater system designers, installers, maintenance workers, manufacturers, and inspectors. For example, ATUs have pumps that require annual maintenance. Currently, there aren’t enough workers to meet the projected demand for the various technologies that will eventually replace cesspools.

Coleman hopes that creating accessible, affordable community college programs will create and bring jobs to the state, but ultimately help spread cost-effective cesspool and even septic alternatives. “All of this is in an effort to drive down the cost of converting cesspools, getting more competition and more labor,” he says.

Reyher-Colon is also part of ongoing efforts to educate Hawaiʻi residents about the need for workforce development for the wastewater industry and the growing need for cesspool conversions.

“It’s an industry that is really not talked about a lot, as far as recruitment,” she says. And in the same way that Hawaiʻi residents don’t yet fully realize that cesspools themselves are an urgent problem, “a lot of folks don’t realize that there’s opportunities for work within the water and wastewater industry.”

As technology options and groundwater levels rise in tandem, it’s a race to see whether Hawaiʻi can meet its 2050 deadline, protecting not only its sandy shores and crystalline seas, but its less visible groundwater ecosystems and communities, too. Leaders like Reyher-Colon, a 14th generation Hawaiian, remain hopeful: “It’s all of our kuleana, our responsibility, both as professionals in the industry as well as community members, that we find solutions not just for ourselves in the industry, but for our families who will be impacted,” she says. “And, of course here in Hawaiʻi, we’re all family.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE