Designing mesocosms with help from my home aquarium

By Zack Rago

We generally think of ecology as the study of interactions between organisms and their environment. This can be easier said than done. Ecosystems are unimaginably complicated at every scale, from the microscopic world to patterns so large they can be seen from space.

As a result, creating a comprehensive understanding of an ecosystem poses many challenges. On the one hand, we can conduct field surveys and make observations in nature, which provide a wealth of information but at times can limit the questions we are able to answer. On the other hand, we can create highly controlled experiments in a laboratory, which may shed light on a particular question but lack real-world connections to the environment.

There is, however, another way to explore critical questions: mesocosms. At their simplest, a mesocosm is an experiment conducted within an enclosure of the natural world. They are a lovely balance between field observation and controlled experiment, and this is the type of study I am conducting for my research at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) as a Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Graduate Fellow.

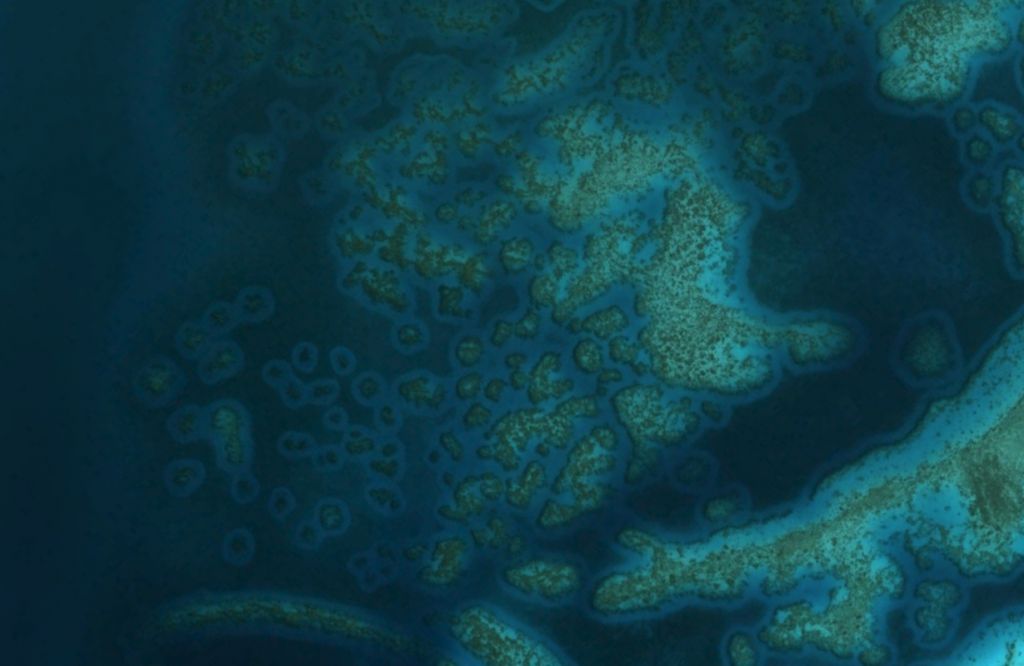

I currently study how the density of predators and prey influence the formation and size of coral reef halos. A coral reef halo is an over-grazed or barren ring around a central patch of coral reef within meadows of algae or seagrass. These halos occur in reef systems around the world and under a variety of conditions. The barren area is theorized to be the consequence of cautious herbivores only willing to graze on algae or seagrass at a certain distance away from the protection of the coral reef. I am investigating how different numbers of predators or herbivores change the distance that herbivores are willing to reach in order to graze. To explore this question, I have set up a system of mesocosms at HIMB that allows me to keep all environmental variables constant while also being able to alter the numbers of herbivores and predators at will. Designing and maintaining these mesocosms may sound like a challenge, with a steep learning curve, but thankfully I have been able to rely on skills I began developing in my youth.

I started my first aquarium when I was 12 years old and was immediately fascinated by the ability to replicate a complex coral reef ecosystem in my living room. In fact, I was so fascinated that I made a career out of it, working for nearly a decade as a professional aquarist. Perhaps what I love most about aquariums is that even after all these years, not a day goes by where I don’t learn something new or have to alter a longstanding practice. In a way, becoming an aquarist encompasses the essence of what we do in science: always building upon the body of knowledge to create a better tomorrow, whether that is discovering a better method for stabilizing the alkalinity of your personal tank, or conserving the natural wonders of our fragile planet. Along my journey, I always craved the space to apply my skills to scientific research, and last year I took the opportunity to pursue my PhD at HIMB knowing that I could do just that.

My mesocosms require thoughtful design that ensures they will be both reproducible and as representative of the natural world as possible. The lessons I learned as an aquarist have been driving forces in my design process and have already helped me overcome obstacles in the process. My pilot-study mesocosms have recently been deployed, and I am excited to analyze the results.

With science or home aquariums, there will undoubtedly be hang-ups along the way, but that is all part of the experience that will inevitably make me and my results better in the end. I am only at the beginning of my journey in research, but I hope I can soon share the details of what my mesocosms unravel about the mysterious coral reef halos.

About the author:

About the author:

Zack Rago is PhD student studying coral reef ecology in the Madin Lab at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology. He is passionate about working with aquarium systems both as a hobbyist and scientist.