The Little Red Wheelbarrow

by Gina McGuire

Growing up, I could often be seen pushing a tiny, red wheelbarrow, lightly filled with soil, following along behind my parents as they created their small world of green: a native canopy and understory of hāpuʻu and ʻōhiʻa with sweet smelling maile vines below. In the rain-soaked, green world of Hawaiʻi Island, I came to understand how we could support the forest, and in turn, the forest would sustain us, literally feed us, but also nourish our dreams.

Restorative forest work is hard, but there is an underlying beauty to it recognized by the generations who have come before, showing us the value in getting your knees dirty. Pushing that wheelbarrow, I didn’t know that 20 years later I would be modelling agroforest systems in Hawaiʻi like the maile-filled forest my father had restored when I was a little girl. I am fortunate to do this as a Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Graduate Fellow alongside an amazing team of researchers

There are a whole host of practices that physically integrate traditional agricultural crops with trees, where agroforestry systems are just one such possible practice, alongside examples like living fences or culturally-managed native forests. Multi-level agroforests are similar to natural forests in having a mix of species that preferentially grow to different heights, providing diversity in the structure and function of the forest system. These agroforests have long been important to Hawaiian culture and food production. In fact, an analysis of the spatial distribution of pre-contact Hawaiian agroforests by Dr. Natalie Kurashima and team shows that Indigenous agroforest systems may have produced even more food than wetland loʻi (taro cultivation).

Hawaiʻi is in a major transitional period since plantation agriculture left the islands, where the future of our agricultural lands is highly uncertain. In 1978-1980, about 255,786 acres across the Hawaiian Islands were under management of the sugar industry (via data from Dept. of Agriculture). However, since the departure of the sugar industry, there are about 87,000 acres of land across the state previously used for agricultural that are now considered “un-managed,” according to a statewide 2015 Agricultural Baseline map. This is a huge opportunity for restoring historical systems like agroforestry in a contemporary context, for ecological, cultural, and economic benefits. How to accomplish this and what the benefits might be for all Hawaiʻi are critical policy questions.

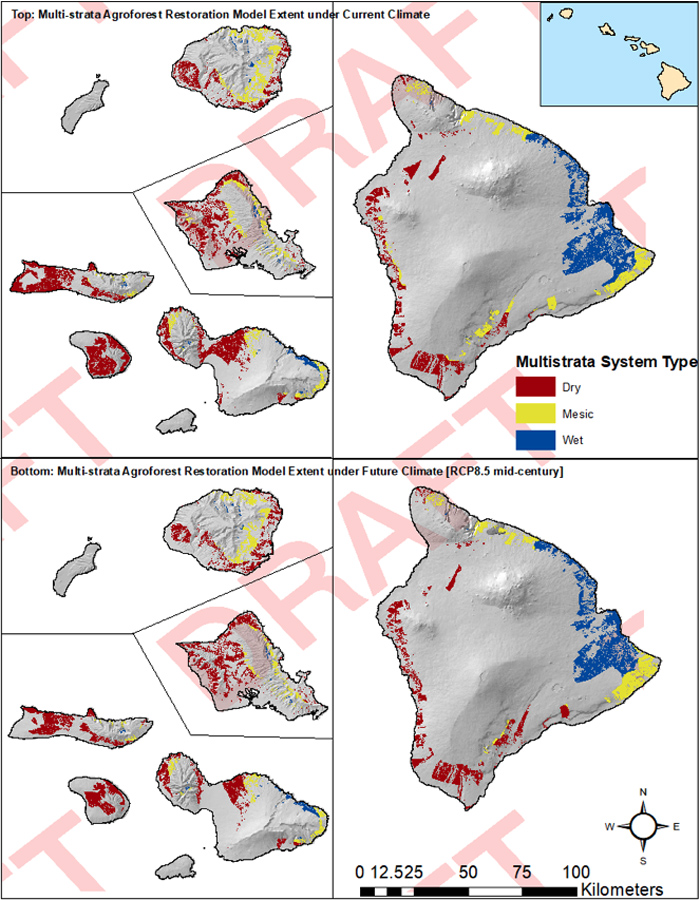

Our current research is informed by interviews that Zoe Hastings conducted with agroforest practitioners across the state, as well as by conversations with current practitioners of silvopasture (i.e. tree and livestock integrated systems, like raising koa and cattle together). We have also gained valuable insight from examining on-the-ground agroforestry sites, including places currently being restored and others with historic agroforest remnants, which have helped us to evaluate the synergies and tradeoffs in benefits across our islands. We are considering the potential for restoration on all agricultural lands across the state that are not currently in production (i.e., not ranch lands or those with current crop cultivation), as well as sections of rural-, conservation-, and urban-zoned lands where they overlap with historic sites of Indigenous systems. To improve identifying areas where multi-strata agroforests can be grown, our model includes all lands ranging from sea level to 3,000 feet elevation that have flat to gentle slopes (under 30 degrees).

Restoration of these lands to agroforest systems would enable cultivation of many useful products, such as food, medicine, and timber while providing a host of other ecosystem services, such as enhanced biodiversity, biocultural services, and sediment retention. I am particularly excited at this point in our work to think about the potential benefits of multi-strata agroforest systems for carbon storage, including soil carbon.

Organic carbon content is an important indicator of soil health, shaping the soil’s chemical make-up and biological productivity and increasing its capacity to hold nutrients. We are currently designing a way to understand the benefits of agroforest restoration on soil carbon in un-managed agricultural lands across the state, drawing on existing studies from Hawaiʻi. These can establish where restoration has led to clear benefits, and where there are still uncertain effects. For example, while there may be clear increases in above-ground carbon sequestration or increased biodiversity when agroforest restoration is implemented, the specific effects on soil carbon are uncertain, depending on soil type, land use history, and management practices.

In addition to this statewide modelling of potential benefits, we have looked at two primary sites to understand the effects of their land-use histories and the potential of modern agroforestry systems. The first site at Puʻulani in Heʻeia, Oʻahu, is stewarded by a community of practitioners and researchers, including Dr. Leah Bremer, Zoe Hastings, and the non-profit Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi. I am conducting my PhD research at the other site, Kalapana on Hawaiʻi Island, where I seek to understand wellbeing in coastal plant and human communities alongside community practitioners. It is my hope that this work can inspire and inform the cultivation of diverse agroforests across the state, creating a future where keiki of Hawaiʻi will grow up pushing little red wheelbarrows of healthy soil intended to sustain our people.

Further reading of interest on agroforestry:

Hastings et al. (2020) Integrating co-production and functional trait approaches for inclusive and scalable restoration solutions

Kurashima et al. (2019) The potential of indigenous agricultural food production under climate change in Hawaiʻi

Kamehameha Schools study (2019): Indigenous agriculture has strong potential to contribute to food needs under climate change

Hubanks at al. (2018) Getting the Dirt on Soil Health and Management

About the author:

About the author:

Gina McGuire is a third year PhD student in the Geography & Environment Department at UH Mānoa who aspires to work with Indigenous lands and communities to advocate for their wellbeing. Her favorite tree (today, anyway!) is the manele (soapberry).