How the Knauss Fellowship has shaped my view of science

by Sarah Tucker

It’s 11 am on a sunny, but chilly, June morning off the coast of Nome, Alaska. Hundreds of small pieces of broken and melting sea ice are sprinkled across the dark gray waves as far as the eyes can see. I am standing on the deck of the R/V Sikuliaq (see-KOO-lee-auk, Iñupiaq for young sea ice) as it is entering port. Over the past few days, we traversed the frigid Bering Sea, passing through the Aleutian Islands from our original port of Seward, Alaska.

This past June I had the opportunity to join an Arctic Chief Scientist Training Cruise, supported by UNOLS/AICC. With a cohort of graduate students, post-docs, and young professors, we spent our time at sea collecting seawater samples, sediment cores, and other ocean and wildlife observations and in training sessions to learn how to serve as a chief scientist on Arctic research cruises. This included discussing the necessary leadership and knowledge for handling the responsibilities that go along with taking groups of people out to sea on a scientific mission.

Each participant of the program also had the opportunity to serve as co-chief scientist for a day. As “acting chief scientist,” I was surprised by the sheer amount of decision-making and communication encountered in a single day of science activities. The chief scientist is a point of contact among the deck-hands, the science party, and ship’s captain and needs to be able to adapt quickly to changing conditions and communicate well to ensure efficient and safe scientific activities.

During my time on the chief scientist training cruise, I recognized that my current position as a Sea Grant John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellow had prepared me to approach this experience with fresh eyes and new skills. My office at NOAA, the Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing (GOMO) Program, is responsible for coordinating, supporting, maintaining, and strategizing when, where, and how ocean observations are being collected to expand our understanding of the ocean and improve our ability to predict how the ocean is changing. While I had previous experience conducting science on a research vessel before and understood the amount of work it took to plan and conduct research activities, as a Knauss Fellow now, I was intimately aware of the role of government agencies in keeping research expeditions going. In other words, I was learning the amount of behind-the-scenes effort that went into planning, budgeting, strategizing, communicating with the public and Congress, engaging with state and international governments, and mitigating conflict.

In the Arctic, this work spans a complex spectrum, including topics like: ensuring that researchers have access to ships that are capable of navigating sea ice and are equipped with proper technologies; gaining Congressional support to develop and implement plans for an Arctic Observing Network; and engaging with local communities in Alaska to prevent scientific activities from impacting daily life, like subsistence hunting or whaling. I have participated in and advanced these activities through my Knauss Fellowship position at NOAA and as a secretariat member of the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee, an interagency working group of the White House’s National Science and Technology Council that brings together leaders from across the Federal government to enhance research in the Arctic.

My experiences thus far as a Knauss Fellow have changed how I regard research cruises, the role of scientific leadership, and even the research. I have a new appreciation for the necessity of the research community to have access to ship time and icebreakers, as well as for the costs to maintain these research platforms. In parallel, I also have a better understanding of the impact scientific research expeditions can have on local communities and the necessary work required to minimize these impacts and improve communications between scientists and communities. Perhaps because I am involved in strategic planning for Arctic research, I have also found that the science has a sense of urgency in a way I had never felt before.

Most pointedly, my understanding of leadership has changed. Decisions and discussions that once felt so far away from me are something I am now involved in and welcomed to participate in. I have had incredible opportunities to host the heads of 18 different agencies during the IARPC Principals Meeting and to shadow Dr. Rick Spinrad, the Administrator of NOAA. During these engagements with leaders, the importance of clear and continuous communication, and an investment in the team relationships has stood out to me.

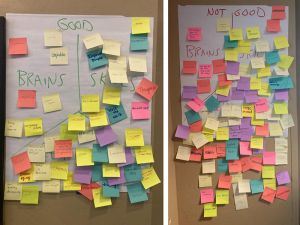

As I approach new challenges and opportunities, whether it is being a chief scientist or developing policy in a high-level meeting, I hope to remember an activity I participated in during the NOAA Women’s Leadership Workshop. Each person listed five attributes each of a good and bad leader. We then sorted them into three categories based on whether the attributes were related to their brains, skills, or relationships. The category that received far-and-away the most attributes was relationships. In other words, how a leader handles their relationships is very likely to define them, for better or worse.

Science is formed on a foundation of diverse relationships, connecting scientists, communities, industry, policymakers, government agencies, media, and students. These relationships are vital to ensuring that the science is understood and utilized, but also avoids negative consequences.

During the Knauss Fellowship, I have been exposed to many new environments and roles: science communicator, science policy strategist, program manager, web designer, workshop organizer, and editor. By coming back to my roots as a researcher through the chief scientist training cruise and time at sea in the Bering, I was able to truly recognize this growth and see how much I’ve gained. While I knew the Knauss Fellowship would help me expand my view of marine science and policy, I had no idea how fundamentally this experience would shape my view of science and the roles I would like to fill as a scientist.

About the author:

Sarah Tucker is a Knauss Fellow in NOAA’s Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program through the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Program. Her scientific interests include marine microbiology, genomics, community-based research, and oceanography. When she is not science-ing, she likes to surf, hike, swim, and spend time with friends and family.