A model situation? Assessing nutrients in coastal groundwaters

by Brytne Okuhata

Imagine this: you take a deep breath and jump into the ocean. The water surrounds you and flows through your hair. You come back up to the surface and soak in the beauty around you. But invisible to you and floating all around are microscopic nutrients. We usually think nutrients are good for us, but these nutrients came from an unpleasant source: cesspools, hundreds of cesspools, located under almost every house, in every neighborhood, flushing into the ground and polluting our freshwater resources.

It’s no secret that cesspools have been causing problems in Hawai‘i. Raw sewage accumulates in an underground hole beneath too many homes and slowly discharges, filtering through the soil surrounding it. But with heavy rain, that sewage comes into contact with groundwater before filtering can occur, and flushes towards the coastline where it integrates with the ocean, the same ocean where we swim and play, and the same ocean that sustains our coastal ecosystems. Excess nutrients are commonly sourced from human-derived inputs, like sewage, and are harmful to groundwater-dependent ecosystems. One of these nutrients, nitrate, is produced by many different sources, including natural ones, which often makes it challenging to determine where excess nitrate originates.

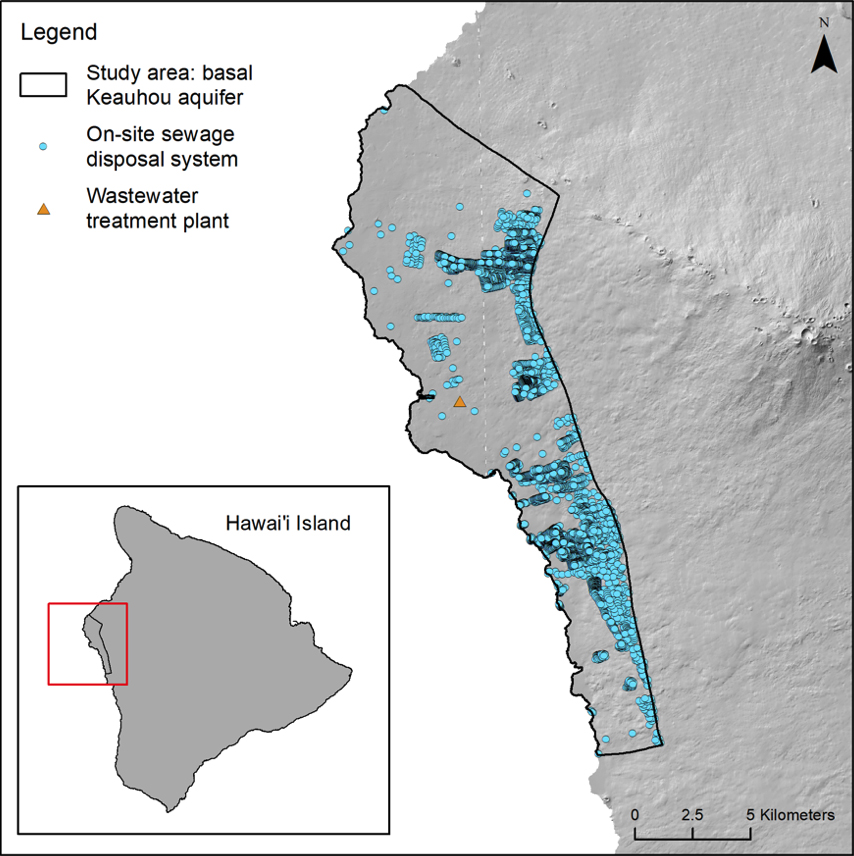

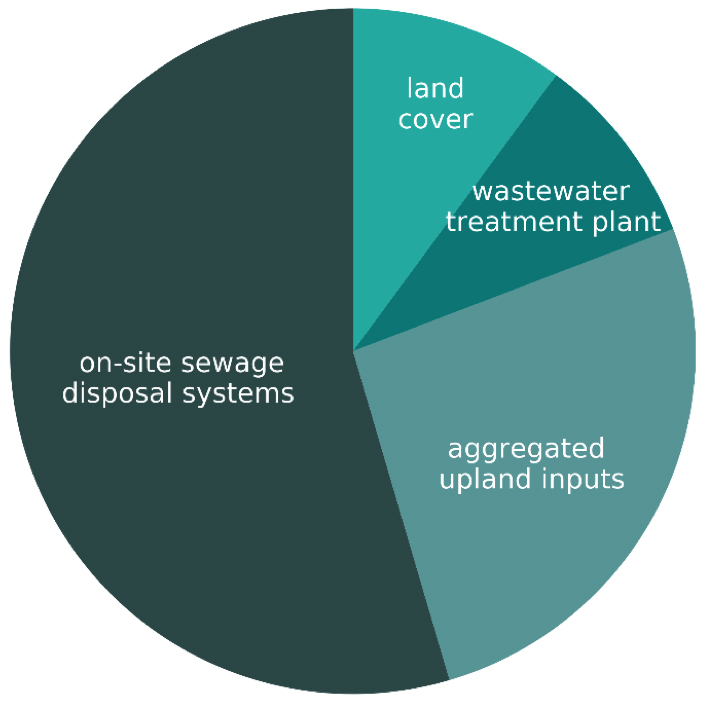

My work as a Hawaiʻi Sea Grant Graduate Fellow involves developing a model to replicate groundwater conditions in the coastal area of Keauhou, located on the west side of Hawai‘i Island. With this model, we intend to quantify how much nitrate flows through the Keauhou aquifer by assessing likely nitrate sources, such as on-site sewage disposal systems (OSDS), the wastewater treatment plant, land cover, and groundwater from the upland aquifer.

Model results so far suggest that cesspools are the primary culprits, contributing more than half of the nutrients across the entire shallow groundwater area. However, other nutrient sources can’t be ignored, such as the Kealakehe wastewater treatment plant, located less than two kilometers from the shore. While the wastewater treatment plant seemingly contributes a relatively small proportion of nutrients, they are released into a small area right near the coastline. Nutrient concentrations are therefore much higher directly around the wastewater treatment plant and should not be overlooked.

The state of Hawaiʻi has been working on this problem by continuing their efforts to find alternatives to cesspools, which would help mitigate nutrient inputs to the groundwater and ocean. Such efforts include the passing of Act 125, which requires all cesspools in Hawai‘i be upgraded by 2050. Additionally, the Kealakehe wastewater treatment plant will potentially be upgraded to produce high-grade, R-1 recycled water, which would decrease the amount of nutrients discharged into the ground. These efforts, however, come with substantial costs, which can prove prohibitive for some homeowners to convert their cesspools to a more clean and efficient system.

My modeling work (recently published; doi:10.1007/s10040-021-02407-y) can help those decisionmakers assessing whether efforts should first go towards converting cesspools or instead be directed towards upgrading the wastewater treatment plant. Contamination from the different sources impacts the groundwater system in slightly different ways, so there is no simple, single answer to what is the “best” path. Ultimately, all efforts will be required to maintain and preserve the environment around us.

So, the next time you take that breath and jump into the ocean, think about how you can help to ensure it is safe for years to come.

About the author:

About the author:

Born and raised on Maui, Brytne Okuhata is a PhD candidate in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. During her years as a graduate student, she has used numerical models, geochemical tracers, and geophysical tools to study Hawai‘i’s groundwater.