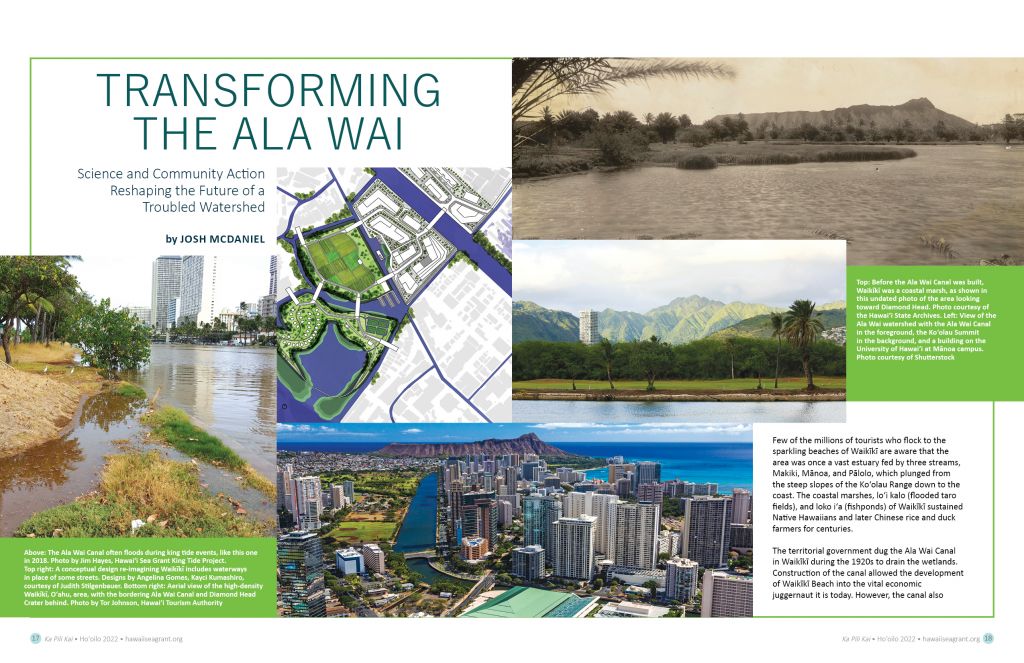

Few of the millions of tourists who flock to the sparkling beaches of Waikīkī are aware that the area was once a vast estuary fed by three streams, Makiki, Mānoa, and Pālolo, which plunged from the steep slopes of the Ko‘olau Range down to the coast. The coastal marshes, loʻi kalo (flooded taro fields), and loko iʻa (fishponds) of Waikīkī sustained Native Hawaiians and later Chinese rice and duck farmers for centuries.

The territorial government dug the Ala Wai Canal in Waikīkī during the 1920s to drain the wetlands. Construction of the canal allowed the development of Waikīkī Beach into the vital economic juggernaut it is today. However, the canal also destroyed the wetlands and flooded agricultural fields, which had functioned as a sponge that prevented flooding and acted as a natural filtration system that absorbed nutrients and captured sediment before they reached the ocean.

As the population of Honolulu grew, so did the flow of pesticides, bacteria, heavy metals, and even raw sewage into the Ala Wai, and eventually into the ocean. The Ala Wai is now one of the most polluted waterways in Hawai‘i, with stagnant waters supporting conditions that are ideal for Vibrio vulnificus, a bacterium that can cause life-threatening skin infections. Invasive species in the upper watershed have increased erosion, resulting in sedimentation of waterways, while urban development has amplified stormwater runoff, straining the ability of the canal to discharge sufficient water to prevent flooding.

In 2006, heavy rains damaged a major sewage line, forcing the city to dump 48 million gallons of raw sewage into the Ala Wai over a five-day period. The spill forced the closure of Waikīkī beach for a week.

And wastewater continues to plague the watershed. According to the Hawai‘i Department of Health, there are more than 11,000 cesspools on Oʻahu, with a large proportion in the Ala Wai watershed. Many of these leaky cesspools leach human waste and wastewater into streams, groundwater, and eventually the Ala Wai and ocean beyond.

But the tide may be turning on the toxic state of the Ala Wai.

Water quality researchers are developing systems to monitor pollution levels and warn the public about dangerous conditions in the canal, as well as the effects of outflow on the waters of Waikīkī. Community groups are now advocating for policies that address pollution in the canal and flooding in the lower watershed while restoring streams and building resilience throughout the watershed. Others have proposed returning wetlands to Waikīkī by converting the canal and adjacent golf course into marshes, loʻi kalo, and loko iʻa that would help improve water quality and absorb stormwater and high tides related to sea-level rise, while providing recreational opportunities.

What lives in those murky waters?

Planners originally designed the Ala Wai to have two outlets in a horseshoe shape bracketing present-day Waikīkī Beach — the current outlet at Ala Wai harbor and a second one near Kapiʻolani Park. Engineers abandoned construction of the second outlet in 1929 during the Great Depression when funding ran out and they realized currents would take the outflow right along Waikīkī Beach.

Without the second outlet, however, the eastern half of the canal essentially became a stagnant pond that traps contamination. The lack of flushing causes problems with water quality, including an accumulation of dangerous bacteria, such as Vibrio vulnificus, the notorious “flesh-eating” bacteria.

Dr. Olivia Nigro, a microbial ecologist in the Department of Natural Science at Hawai‘i Pacific University, says Vibrio vulnificus occurs naturally in warm, brackish waters, where freshwater mixes with seawater. “When conditions are right, the canal is an ideal incubator of Vibrio,” she says.

In addition, high levels of nutrients from nitrate and phosphate pollution provide a ready food source that drives Vibrio abundance higher. “Overfertilization upstream leads to plenty of food for bacteria to metabolize in the Ala Wai,” says Nigro.

Nigro points to SMART (Strategic Monitoring and Resilience Training) Ala Wai, a student-led University of Hawai‘i water quality monitoring project, as a way to collect data that could allow real-time predictions of when and where pathogens are more abundant.

SMART Ala Wai was an effort to create a comprehensive monitoring and sampling network throughout the watershed using low-cost sensors built and maintained by undergraduate and secondary students. The project introduced students to the possibilities of using science and technology to address environmental issues, while also disseminating data for public education and engagement.

Dr. Brian Glazer, professor of oceanography at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, says SMART Ala Wai helped engage and train a generation of young scientists while also providing a wealth of water data, from basic data on precipitation, stream water levels, and groundwater throughout the watershed, to water quality in the Ala Wai.

“We wanted to quantify what was flowing into the Ala Wai — sediments, nutrients, even carcinogens associated with brake dust from road runoff,” says Glazer. “And then learn how those inputs affect what’s living in the canal. And, of course, where does the water go? How does it impact Waikīkī Beach?”

While funding for SMART Ala Wai ended in 2019, several researchers, community groups, and schools have maintained smaller pieces of the project.

The community takes action

Over the past decade, community groups and projects have flourished across the Ala Wai watershed. The groups have a wide variety of aims and projects, from neighborhood stream cleanups to environmental education and civic engagement, water quality monitoring, stream and forest restoration, and stormwater system improvements.

The Ala Wai Watershed Collaboration launched in 2015 with support from Hawai‘i Green Growth to develop a collaborative vision for the watershed.

“We are working to create a resilient watershed from mauka to makai, from mountain to ocean,” says Casey Maslan, the lead for the Ala Wai Watershed Collaboration. “Our goal is cross-collaboration to build a more prosperous and resilient watershed for everyone.”

The focus of many of the organizations in the collaboration turned to flooding when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) proposed a $345 million flood control project for the watershed in 2018 that included controversial ideas for detention basins in upper watershed neighborhoods, and concrete walls along the Ala Wai Canal. The plan met with fierce opposition from a broad array of community groups.

In 2019, the grassroots organization Protect Our Ala Wai Watershed (POAWW) successfully sued to hold up funding for the project. USACE revised its original plan, specifically removing controversial neighborhood detention basins from the plan, and it is currently completing an updated study of flood risk in the Ala Wai watershed.

POAWW President Sidney Lynch says that many in the community want officials to include more holistic approaches beyond the proposed expensive “grey” infrastructure measures. They are promoting nature-based solutions, such as forest management to control erosion and sedimentation, and stream restoration and stormwater retrofits throughout the watershed to reduce runoff and improve water quality.

Eric Merriam, a USACE planner, says that the Ala Wai study does not have “ecosystem restoration authority,” and that anything the agency implements has to be for flood risk management purposes, with environmental benefits being a secondary consideration.

“We can consider nature-based flood risk management measures, like construction of wetlands or taro fields which act as a giant sponge absorbing water, but we can’t implement a measure purely to have ecological benefits,” Merriam says.

“The Army Corps says it can only target flood mitigation — and pollution in the Ala Wai Canal is not its concern,” Lynch says. “We’re saying, ‘Hey, we can clean up the Ala Wai and address flooding at the same time.’”

Merriam stresses that the project team is analyzing public recommendations for solutions to flooding, such as using existing greenspace for detention basins, managing invasive species of plants in the upper watershed, and possibly using the Ala Wai Golf Course as a storage basin for floodwaters.

“The communities are very passionate. They live in the watershed, and they have valid ideas about how to address flood risk,” Merriam says. “That’s an asset for the project that will benefit everyone in the watershed.”

Re-imagining the Ala Wai

Judith Stilgenbauer has a vision for Waikīkī and the surrounding area inspired by Native Hawaiian knowledge of the role of wetlands in watersheds. Stilgenbauer, professor and director of the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Hawai‘i, led a design team exploring ideas for adapting the southern shore of Oʻahu for sea-level rise using living shorelines, connectivity, and nature-based solutions.

The team proposed converting the Ala Wai Canal area and neighboring golf course into a patchwork of wetlands, loko iʻa, and loʻi kalo like they once were before canal construction.

“Ancient Hawaiians were incredibly gifted ecological engineers,” Stilgenbauer says. “Where the golf course is now, loʻi kalo, or wetland taro agricultural systems, produced food, but also filtered and treated stormwater as it came down that watershed, capturing sediment and nutrients before they entered the ocean.”

Stilgenbauer wants to bring that knowledge back into use, “not as a romanticized museum-type version, but a 21st century interpretation” that represents a contrast to many of the current hard-engineered solutions.

Along with her students, Stilgenbauer has also developed speculative design proposals for replacing some Waikīkī streets with soft-shored canals that would allow water to flow through Waikīkī to the re-imagined Ala Wai Canal and restored wetlands as an adaptation to flooding, either because of sea-level rise or from floodwaters generated inland in the watershed. She says living canal edges and other nature-based solutions contribute to biodiversity and a more resilient urban system.

“There could be recreational opportunities, there could be water taxis,” she says. “Look at cities like Melbourne, Sydney, or Vancouver where a lot of transportation happens on the water. It makes sense to bring water back into Waikīkī.”

The growth of community action and visionary leadership from community leaders, scientists, teachers, engineers, and landscape architects has sparked a re-imagining of what’s possible in the Ala Wai. The coming decades will hopefully bring a transformation from the troubled current reality of the urban watershed into a more resilient future built on science, sustainability, and traditions from the past.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE