As Hawai‘i prepares to carry out a massive overhaul of its numerous cesspools by 2050, the state finds itself in a quandary — waste treatment is expensive, and homeowners’ pockets only run so deep.

“This is one of the biggest burdens the state is facing because it’s a $2 – 4 billion problem,” said Stuart Coleman, executive director and co-founder of Wastewater Alternatives and Innovations (WAI) and a member of the Hawaiʻi Department of Health’s Cesspool Conversion Working Group.

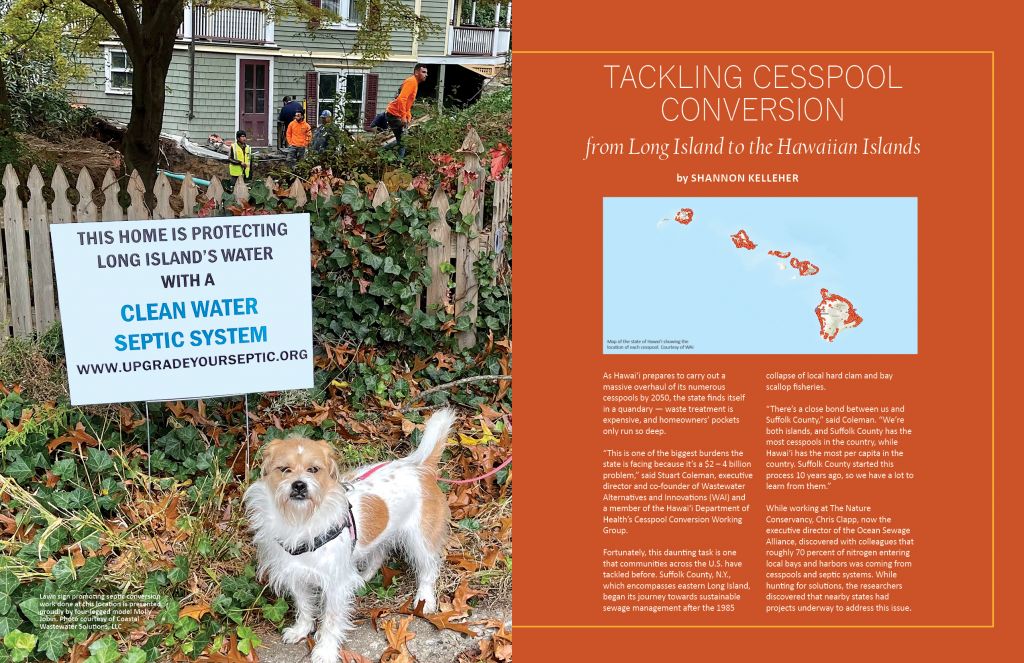

Fortunately, this daunting task is one that communities across the U.S. have tackled before. Suffolk County, N.Y., which encompasses eastern Long Island, began its journey towards sustainable sewage management after the 1985 collapse of local hard clam and bay scallop fisheries.

“There’s a close bond between us and Suffolk County,” said Coleman. “We’re both islands, and Suffolk County has the most cesspools in the country, while Hawai‘i has the most per capita in the country. Suffolk County started this process 10 years ago, so we have a lot to learn from them.”

While working at The Nature Conservancy, Chris Clapp, now the executive director of the Ocean Sewage Alliance, discovered with colleagues that roughly 70 percent of nitrogen entering local bays and harbors was coming from cesspools and septic systems. While hunting for solutions, the researchers discovered that nearby states had projects underway to address this issue.

Soon after, officials from Suffolk County, the Environmental Protection Agency, New York State, and The Nature Conservancy were traversing the coast on a “magical septic tour.”

“I kid you not, in the middle of that tour, some of the officials who were in the camp of ‘none of this stuff works; it costs too much; you’re going to have geysers of poop shooting in the air’ said, ‘Okay, this is great,’” said Clapp. “That regulator-to-regulator learning experience was invaluable.”

Eventually, Suffolk County arrived at a solution for most individual households to rely on innovative and alternative (IA) wastewater treatment systems, which cost about a sixth as much as connecting to a neighborhood sewer pipe. To finance the conversions, it instituted a program that pays $10,000 to $15,000 of the cost per homeowner. The state pays another $10,000 to $15,000.

“After they receive this financial aid, most homeowners are left with very little to cover,” said Clapp. “In many cases homeowners are out the $2,500 for initial engineering and planning, and some costs associated with additional site restoration or landscaping.”

“We didn’t reinvent anything — we tried to build a better program based on lessons learned from several other jurisdictions,” said Justin Jobin, a former environmental projects coordinator who has worked with both Suffolk County and Rhode Island state.

Even with its steady stream of revenue, Clapp says Suffolk County’s wastewater makeover is nowhere near completion. Still, it’s an example Coleman thinks Hawai‘i could learn from.

Far south, in the balmy waters of the Florida Keys, the porous coral islands of Monroe County have taken a different approach to tackling sewage challenges following legislation that requires advanced wastewater standards.

“Every house and every business had its own wastewater system, with the exception of the city of Key West,” said Kevin Wilson, the assistant county administrator. “The vast majority of those were abandoned in favor of joining a central system.”

Today, Monroe County has 12 central wastewater treatment plants, and Wilson believes that no more than 70 septic tanks remain in service. To make the transition affordable, it allowed homeowners to amortize fees over a period of 20 years on their property tax bill and offered grant funding.

“Originally, FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] disaster recovery money from Hurricane Wilma and Tropical Storm Fay was used to arrange monetary assistance for low-income homeowners to make the final connection between their house and the central connection system,” said Wilson. “More recently, we have received funds to help low-income homeowners connect to the central system through the State Housing Initiatives Partnership (SHIP) program. Importantly, we’ve used sales tax dollars to subsidize the cost of the construction of the systems.”

Today, the program is operational, and the county government need only pay off the debts for which they have pledged future sales taxes.

“I’m sure we’ve made a positive contribution,” said Wilson. “We’re removing 95-99 percent of organic loading from 160,000 people on the islands using the bathroom. That’s got to be a good thing.”

While Coleman believes that Hawaiʻi can learn from other states, he notes it must contend with its own unique challenges. However, he also sees opportunities.

Coleman noted, “Working with partners like Hawai‘i Sea Grant and the community colleges, WAI created the Work-4-Water (W4W) Initiative during the pandemic, when Hawai‘i went from having the lowest unemployment rate in the country to having the highest because of our over-dependence on tourism. To convert 88,000 cesspools by 2050 means we need to start converting about 3,000 cesspools per year. We’re currently only doing about 150-200, so we estimate there will need to be hundreds, if not thousands, of new jobs to do this work.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE