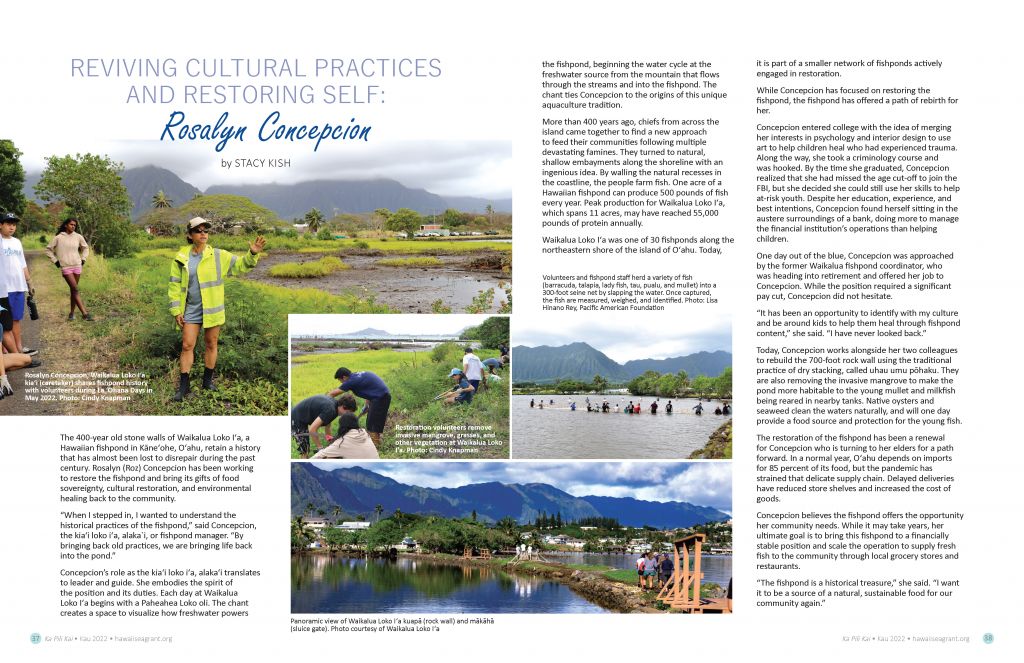

The 400-year old stone walls of Waikalua Loko Iʻa, a Hawaiian fishpond in Kāneʻohe, Oʻahu, retain a history that has almost been lost to disrepair during the past century. Rosalyn (Roz) Concepcion has been working to restore the fishpond and bring its gifts of food sovereignty, cultural restoration, and environmental healing back to the community.

“When I stepped in, I wanted to understand the historical practices of the fishpond,” said Concepcion, the kiaʻi loko iʻa, alaka`i, or fishpond manager. “By bringing back old practices, we are bringing life back into the pond.”

Concepcion’s role as the kiaʻi loko iʻa, alakaʻi translates to leader and guide. She embodies the spirit of the position and its duties. Each day at Waikalua Loko Iʻa begins with a Paheahea Loko oli. The chant creates a space to visualize how freshwater powers the fishpond, beginning the water cycle at the freshwater source from the mountain that flows through the streams and into the fishpond. The chant ties Concepcion to the origins of this unique aquaculture tradition.

More than 400 years ago, chiefs from across the island came together to find a new approach to feed their communities following multiple devastating famines. They turned to natural, shallow embayments along the shoreline with an ingenious idea. By walling the natural recesses in the coastline, the people farm fish. One acre of a Hawaiian fishpond can produce 500 pounds of fish every year. Peak production for Waikalua Loko Iʻa, which spans 11 acres, may have reached 55,000 pounds of protein annually.

Waikalua Loko Iʻa was one of 30 fishponds along the northeastern shore of the island of Oʻahu. Today, it is part of a smaller network of fishponds actively engaged in restoration.

While Concepcion has focused on restoring the fishpond, the fishpond has offered a path of rebirth for her.

Concepcion entered college with the idea of merging her interests in psychology and interior design to use art to help children heal who had experienced trauma. Along the way, she took a criminology course and was hooked. By the time she graduated, Concepcion realized that she had missed the age cut-off to join the FBI, but she decided she could still use her skills to help at-risk youth. Despite her education, experience, and best intentions, Concepcion found herself sitting in the austere surroundings of a bank, doing more to manage the financial institution’s operations than helping children.

One day out of the blue, Concepcion was approached by the former Waikalua fishpond coordinator, who was heading into retirement and offered her job to Concepcion. While the position required a significant pay cut, Concepcion did not hesitate.

“It has been an opportunity to identify with my culture and be around kids to help them heal through fishpond content,” she said. “I have never looked back.”

Today, Concepcion works alongside her two colleagues to rebuild the 700-foot rock wall using the traditional practice of dry stacking, called uhau umu pōhaku. They are also removing the invasive mangrove to make the pond more habitable to the young mullet and milkfish being reared in nearby tanks. Native oysters and seaweed clean the waters naturally, and will one day provide a food source and protection for the young fish.

The restoration of the fishpond has been a renewal for Concepcion who is turning to her elders for a path forward. In a normal year, Oʻahu depends on imports for 85 percent of its food, but the pandemic has strained that delicate supply chain. Delayed deliveries have reduced store shelves and increased the cost of goods.

Concepcion believes the fishpond offers the opportunity her community needs. While it may take years, her ultimate goal is to bring this fishpond to a financially stable position and scale the operation to supply fresh fish to the community through local grocery stores and restaurants.

“The fishpond is a historical treasure,” she said. “I want it to be a source of a natural, sustainable food for our community again.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE