Over the past century, wastewater, stormwater, and other pollutants from land and development have damaged our islands’ coastal ecosystems and nearshore waters. This degradation is due in part to the islands’ increasing urbanization coinciding with global warming. Given these immense challenges, many wonder, is there any hope of restoring these coastal areas?

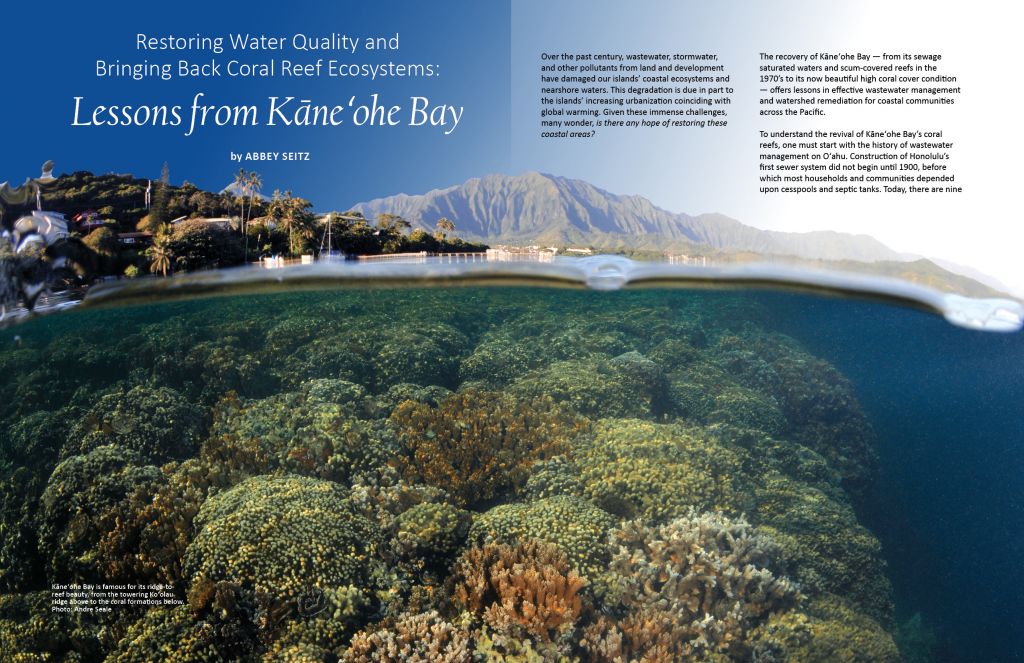

The recovery of Kāneʻohe Bay — from its sewage saturated waters and scum-covered reefs in the 1970’s to its now beautiful high coral cover condition — offers lessons in effective wastewater management and watershed remediation for coastal communities across the Pacific.

To understand the revival of Kāneʻohe Bay’s coral reefs, one must start with the history of wastewater management on Oʻahu. Construction of Honolulu’s first sewer system did not begin until 1900, before which most households and communities depended upon cesspools and septic tanks. Today, there are nine wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and 2,100 miles of sewer pipeline on Oʻahu that are owned/managed by the City and County of Honolulu, Department of Environmental Services (ENV). Before sewage is discharged from an ocean outfall (meaning the point where wastewater enters a water body), it must undergo a multi-stage treatment process to remove organic matter, solids, nutrients, and other pollutants.

Insufficient treatment of outfalls pose major ecological and public health threats. This is particularly true for estuaries and bays, which have shallow depths, low water flow, and limited circulation of oxygen to marine flora and fauna. Today, most sewage outfalls are located in deep bodies of water to protect coastal areas.

However, this was not always the case, and the negative consequences of this is no better exemplified than in Kāneʻohe Bay. From 1963 to 1970, three sewage outfalls associated with new wastewater treatment plants were added to the south, north, and northwestern portions of the bay, directly discharging eight million gallons of sewage per day into the shallow waters of Kāneʻohe Bay. This sewage effluent, in combination with excessive dredging, increased sedimentation, and stream channelization had severe effects. These actions between the 1960’s and 1970’s led to a 70 percent reduction in coral coverage in Kāneʻohe Bay, with up to 95 percent coral loss in areas closest to the sewage outfalls.

Coral decline was largely due to increasing levels of inorganic nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Coral reefs are typically found in tropical waters where nutrient levels are often very low. When nutrients from wastewater or other pollutants are introduced, they stimulate the growth of algae, which can, if grazing herbivores are absent or insufficient in number, overgrow and outcompete corals. The stress caused by nutrients can also make corals more susceptible to bleaching.

More simply put, Kāneʻohe Bay of the late 20th century was a “green bubble of algae,” as described by Dr. Cynthia Hunter, professor and director of the Marine Option Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Due to pressure from local residents and the scientific community, in 1979 the state government began diverting the sewage outfalls to deep water locations outside the bay. This community advocacy coincided with efforts to prevent further suburban development on the Windward side, which had contributed to worsening runoff and wastewater pollution. Surprisingly, soon after the sewage outfalls were diverted, nutrient levels in Kāneʻohe Bay declined and the coral population regrew.

Following the publication and recommendations of the 1992 Kāneʻohe Bay Master Plan, the Kāneʻohe wastewater treatment plant was decommissioned and all sewage from Kāneʻohe and surrounding communities was diverted to the ʻAikahi wastewater treatment plant in Kailua to be treated. While coral abundance had largely recovered by the early 2000’s, because of aging and outdated transmission pipes the bay still experienced regular sewage spills, until recently. Spills typically happened during large storms when the system would become inundated with rainwater and release untreated sewage.

Herb Lee, Kāneʻohe native and executive director of the Pacific American Foundation, was only a child when the sewage outfalls were first built in the bay and remembers “going clamming and only being able to see dirty sewage water.” As an adult in the 1990’s, Lee was instrumental in safeguarding Waikalua Loko Iʻa (fishpond) for community stewardship and cultural use. He often received calls from ENV informing him that untreated sewage had overflowed into the bay. As ENV began considering options to upgrade regional wastewater facilities, Lee and other community leaders fought for new wastewater transmission lines to travel through the Koʻolau mountains, rather than under Kāneʻohe Bay.

The community voices were heard. In 2018, the Kāneʻohe-Kailua Wastewater Conveyance and Treatment Facilities Project was completed. It included the construction of a 3-mile, 10-foot diameter tunnel that transferred sewage to Kailua. It was the largest wastewater system upgrade the island has ever seen, and according to Lee, the bay “hasn’t seen any sewage overflows since the project was completed…The community is much better off now.”

There are important lessons to be learned from the bay’s recovery. According to Dr. Keisha Bahr, former graduate student at the University of Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology and now an assistant professor of marine biology at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, “we should never expect quick results.” Water and sediment trap and slowly release nutrients and other pollutants over time. It can take decades, if not longer, for restoration efforts to reap ecological improvements.

Dr. Hunter emphasized that while the diversion of sewage outfalls was a central component to the bay’s recovery, there are continued interventions that support the local coral reef ecosystem in Kāneʻohe Bay, including the use of algae-reducing technologies (such as the algae “super sucker”) and biocontrol remedies, such as the reintroduction of native sea urchins.

Another lesson is that the physical restoration of the bay has garnered enthusiasm for traditional land stewardship of the bay. Lee, whose organization has engaged thousands of community members and students in stewarding Waikalua Loko Iʻa, says, “Kāneʻohe Bay is home to some of the most talented researchers in the world, who over the last few decades, have been stewarding this resource alongside the community…I never would have imagined this in the 70’s and 80’s.”

Community leaders hope that residents and researchers will carry forward this legacy of advocacy and stewardship of the bay. As Lee says, this will further “bridge the gap between science and Indigenous wisdom.” This will not only bring about improved water quality, but hopefully will catalyze community members to use the bay once again for fishing and other subsistence and cultural activities.

While ecological recovery is not likely to happen overnight, the story of Kāneʻohe Bay demonstrates that not only is there hope for coastal areas to recover after decades of pollution, but through this recovery, the power of community can be harnessed for ʻāina (land) stewardship and education.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE