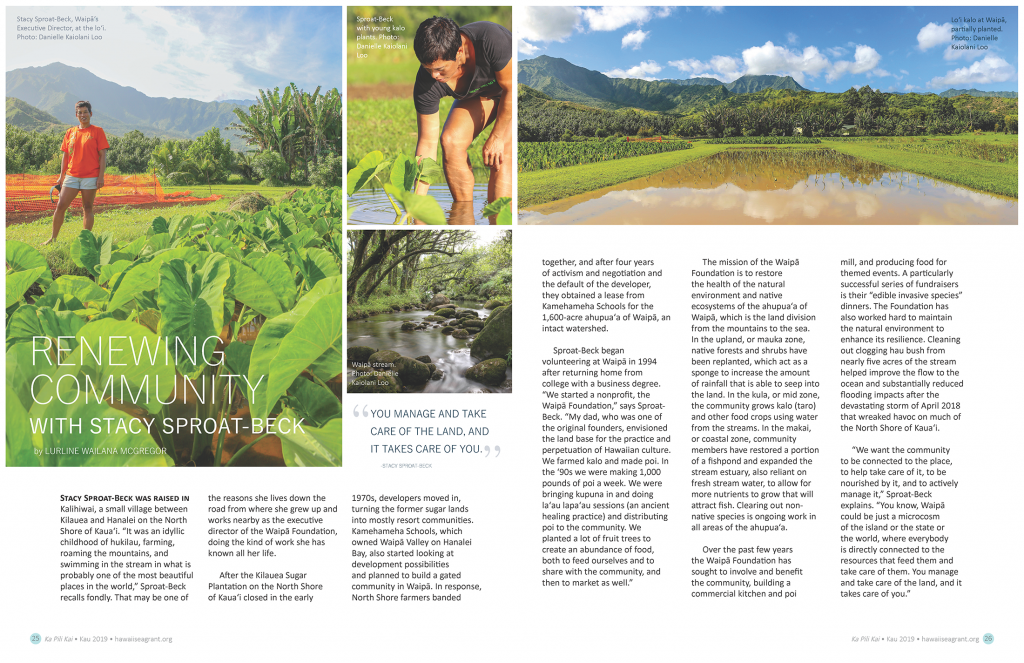

Stacy Sproat-Beck was raised in Kalihiwai, a small village between Kilauea and Hanalei on the North Shore of Kauaʻi. “It was an idyllic childhood of hukilau, farming, roaming the mountains, and swimming in the stream in what is probably one of the most beautiful places in the world,” Sproat-Beck recalls fondly. That may be one of the reasons she lives down the road from where she grew up and works nearby as the executive director of the Waipā Foundation, doing the kind of work she has known all her life.

After the Kilauea Sugar Plantation on the North Shore of Kauaʻi closed in the early 1970s, developers moved in, turning the former sugar lands into mostly resort communities. Kamehameha Schools, which owned Waipā Valley on Hanalei Bay, also started looking at development possibilities and planned to build a gated community in Waipā. In response, North Shore farmers banded together, and after four years of activism and negotiation and the default of the developer, they obtained a lease from Kamehameha Schools for the 1,600-acre ahupuaʻa of Waipā, an intact watershed.

Sproat-Beck began volunteering at Waipā in 1994 after returning home from college with a business degree. “We started a nonprofit, the Waipā Foundation,” says Sproat-Beck. “My dad, who was one of the original founders, envisioned the land base for the practice and perpetuation of Hawaiian culture. We farmed kalo and made poi. In the ʻ90s we were making 1,000 pounds of poi a week. We were bringing kupuna in and doing laʻau lapaʻau sessions (an ancient healing practice) and distributing poi to the community. We planted a lot of fruit trees to create an abundance of food, both to feed ourselves and to share with the community, and then to market as well.”

The mission of the Waipā Foundation is to restore the health of the natural environment and native ecosystems of the ahupua‘a of Waipā, which is the land division from the mountains to the sea. In the upland, or mauka zone, native forests and shrubs have been replanted, which act as a sponge to increase the amount of rainfall that is able to seep into the land. In the kula, or mid zone, the community grows kalo (taro) and other food crops using water from the streams. In the makai, or coastal zone, community members have restored a portion of a fishpond and expanded the stream estuary, also reliant on fresh stream water, to allow for more nutrients to grow that will attract fish. Clearing out non-native species is ongoing work in all areas of the ahupua‘a.

Over the past few years the Waipā Foundation has sought to involve and benefit the community, building a commercial kitchen and poi mill, and producing food for themed events. A particularly successful series of fundraisers is their “edible invasive species” dinners. The Foundation has also worked hard to maintain the natural environment to enhance its resilience. Cleaning out clogging hau bush from nearly five acres of the stream helped improve the flow to the ocean and substantially reduced flooding impacts after the devastating storm of April 2018 that wreaked havoc on much of the North Shore of Kauaʻi.

“We want the community to be connected to the place, to help take care of it, to be nourished by it, and to actively manage it,” Sproat-Beck explains. “You know, Waipā could be just a microcosm of the island or the state or the world, where everybody is directly connected to the resources that feed them and take care of them. You manage and take care of the land, and it takes care of you.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE