The Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant, describes the area of Papahānaumokuākea as the realm of Pō, where life springs from a single coral polyp, and where spirits return upon death.

Papahānaumokuākea got its name in 2007 from two esteemed kūpuna, Uncle Buzzy Agard and Aunty Pua Kanahele, a year after the marine national monument was established

by Presidential Proclamation in order to elevate protections for its biodiversity and rich cultural significance. The name was meant to honor the genealogy and formation of the islands by invoking their ancestral sky mother, Papahānaumoku, and sky father, Wākea, who gave birth to the Hawaiian Islands and their people.

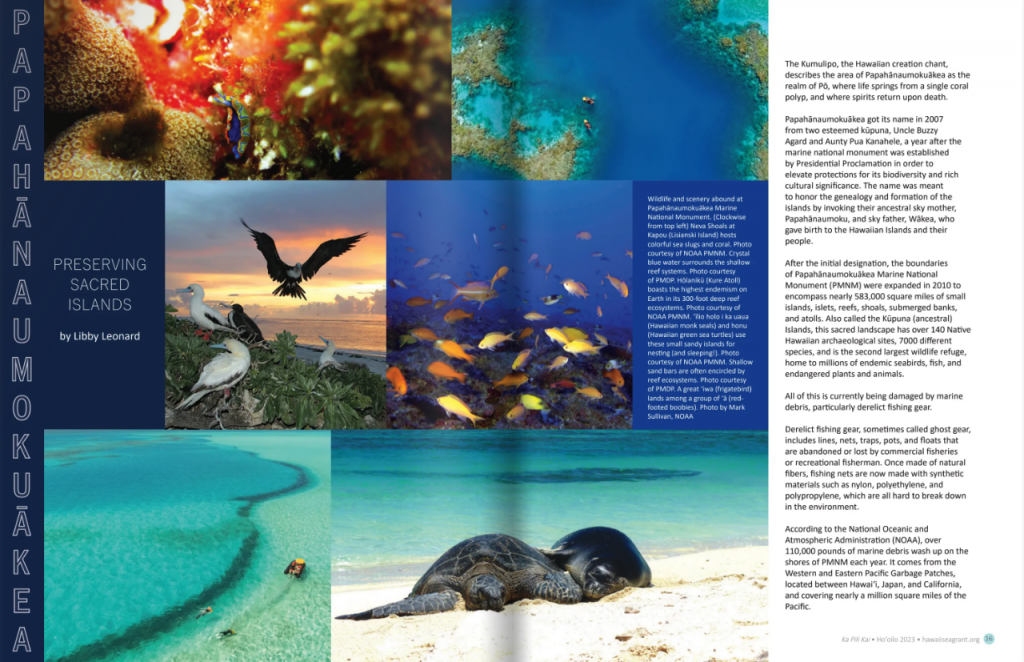

After the initial designation, the boundaries of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) were expanded in 2010 to encompass nearly 583,000 square miles of small islands, islets, reefs, shoals, submerged banks, and atolls. Also called the Kūpuna (ancestral) Islands, this sacred landscape has over 140 Native Hawaiian archaeological sites, 7000 different species, and is the second largest wildlife refuge, home to millions of endemic seabirds, fish, and endangered plants and animals.

All of this is currently being damaged by marine debris, particularly derelict fishing gear.

Derelict fishing gear, sometimes called ghost gear, includes lines, nets, traps, pots, and floats that are abandoned or lost by commercial fisheries or recreational fisherman. Once made of natural fibers, fishing nets are now made with synthetic materials such as nylon, polyethylene, and polypropylene, which are all hard to break down in the environment.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), over 110,000 pounds of marine debris wash up on the shores of PMNM each year. It comes from the Western and Eastern Pacific Garbage Patches, located between Hawaiʻi, Japan, and California, and covering nearly a million square miles of the Pacific.

Research biologist Raymond Boland first studied the impacts of marine debris at PMNM in 1996 when he worked for the National Marine Fisheries Service Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program. Witnessing seals tangled up on beaches made him concerned about what was happening below the ocean’s surface and whether it was a significant source of seal mortality.

On a survey and removal cruise in January 1997, the crew was in the Lalo (French Frigate Shoals) area and came upon a juvenile Hawaiian monk seal entangled in a net securely anchored in about ten feet of water. The seal could still reach the surface but could not escape.

While two other divers leapt into the water to assist the seal, Boland grabbed his camera. “I took that moment to try and capture what was our nightmare: a seal entangled and unable to free themselves and more than likely to drown.”

He shared the photo with NOAA and the United States Coast Guard, and soon, it seemed to be everywhere. That 1997 photo taken of one unfortunately tangled seal catalyzed interest in marine debris and energized the message that something needed to be done. NOAA officially began a formal marine debris removal program about decade later, and since then, they have removed over 2 million pounds of debris.

“There are so many impacts from marine debris that it is easy to overwhelm people and make them feel like it is nearly impossible to solve this problem. It is not. Anything humans put their mind to we can accomplish,” said Boland.

While derelict fishing gear and other marine debris have posed serious choking and entanglement hazards to wildlife and endangered species like the Hawaiian monk seal, the green sea turtle, and humpback whales, debris also highly impacts coral reefs.

With 3.5 million acres, the reefs in PMNM constitute 70 percent of all tropic shallow water coral reef habitat in the United States. Marine debris, particularly the nets, can wear them down, break the coral, or cover and smother the reef structure.

A recent study demonstrated the persistent impacts of marine debris at sites at Manawai (Pearl and Hermes Atoll), where corals showed suppressed growth despite removal of debris.

“We’d seen qualitatively over the years all the time, big nets plastered across this beautiful living bed of coral,” said Kevin O’Brien, one of the co-authors of the study. Once the nets were peeled back, there was often a scar of dead coral underneath from lack of sunlight.

O’Brien reported that they “ultimately found the coral does not bounce back, it becomes a macroalgae dominated system in that net impact site.”

He added that many of the nets found are probably less than six-years-old as older ones get so biofouled that they usually sink and get buried in the sand, or integrated into the reef, where new coral can grow over them.

O’Brien worked for twelve years with the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, conducting and coordinating ship-based marine research missions, including some of the large-scale marine debris removal trips around Papahānaumokuākea, which became a passion project for him.

According to O’Brien, between 2009 and 2021 trips slowed to once every three years to take care of the debris, which he said was partly due to dwindling funds and competition for ship time aboard NOAA research vessels, as well as competition for staff. Wanting to continue to ramp up efforts, in 2019, he started the Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP), a nonprofit which has been conducting month-long clean-up trips bi-annually.

In 2022, their team of 16 freedivers took off on the vessel Imua and collected nearly 100,000 pounds of marine debris from the monument over a 27-day mission. More than 88 percent of that total was ghost nets cleared from a single reef. On a trip soon after, they pulled in another 106,000 pounds.

The team comes from a variety of backgrounds.

O’Brien said that under NOAA, candidates were required to have a four-year degree in marine science and a couple years of field work experience. He and executive director James Morioka decided that for PMDP those qualifications weren’t necessary and eliminated too many who would be perfect for the job.

“There’s a lot of people that grew up in Hawaiʻi who are tremendous in the water, spearfishing, diving, boating, surfing, who may have a cultural connection to the place of Papahānaumokuākea” but may not have the degrees, he said.

When it comes to biocultural conservation practices, O’Brien referenced the Mai Ka Pō Mai, a Native Hawaiian guidance document released in 2021 by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a PMNM co-trustee, to help provide a Native Hawaiian perspective towards the monument’s management.

The groundbreaking guidance document uses cultural concepts and traditions related to Papahānaumokuākea to create a foundation of management practices in all areas. The document offers proper protocols and the application of traditional Native Hawaiian knowledge systems for approaching scientific research, some of which are currently used by Indigenous scientists conducting research at the monument.

With the document’s release, O’Brien’s team member Alika Garcia explored how to implement its recommendations in their work, and even reached out to his kumu (teachers) and mentors for their opinions on how best to integrate the recommended practices. One of the biggest contributions to integrated management comes through kilo, a traditional Hawaiian observational approach, where one takes the time to observe the environment to discover subtleties and nuances.

For Pelika Andrade, culture-based conservation leader with the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (Hawai‘i Sea Grant) and member of the Cultural Working Group that helped create Mai Ka Pō Mai, when talking about Indigenous knowledge systems she says people are easily placed in boxes, like Indigenous scientists in one, and Western scientists in another. But this kind of thought leads others to believe that one has to be Indigenous to practice these knowledge systems when it’s just approaching the inquiry process with the same values and end goals.

Andrade, who is also founder of conservation group Nā Maka Onaona, believes that “in order to address cultural, social, and ecological challenges in conservation, we are recognizing the need to shift our focus towards strengthening the foundational relationships and interconnectedness we have with the world around us, as kānaka ʻōiwi (Native Hawaiians) and members of our Island Earth.”

To her, the marine debris cleanups are a bandage fix, and it is an issue that needs to be taken care of at a global level.

“It’s a global issue that stems from bad behavior, but it also stems from supply and demand and advantageously seeking to promote this whole consumption society that we live in,” she said.

Recently, PMDP and Hawaiʻi Pacific University’s Center for Marine Debris Research (CMDR) partnered with Hawai‘i Sea Grant on a set of NOAA Sea Grant funded projects addressing marine debris. PMDP is leading a project to increase the efficiency of derelict fishing gear removal, and CMDR is working on repurposing gear that is brought to shore. For example, CMDR has been working with the Hawaiʻi State Department of Transportation to repurpose derelict fishing gear by converting it into pellets that are compatible for use in asphalt roads. Hawai‘i Sea Grant is supporting both of these projects with outreach and community engagement, and it is working together with resource managers, educators, and stewardship organizations throughout the Pacific to develop a regional marine debris action plan.

The marine debris cleanup trip conducted in July 2023 removed 86,000 pounds of ghost nets, plastic, and other debris, but it’s not just about the debris, O’Brien said.

“There’s a million NGOs out there doing marine debris cleanups, and we are actually less about the marine debris and more about the place. It’s such a unique place, and we’re the only ones doing this work in the monument,” said O’Brien. “If we stopped today, then there would be no one doing it. And visiting a place in a way where you’re actually giving back to it is really important.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE