There’s an “all hands on deck” effort underway to understand and counter the growing issue of derelict fishing nets and other plastic debris washing up on Hawaiʻi’s shores and reefs, and in its harbors. Organizations and individuals—environmentally conscious volunteers, non-profit organizations, academic researchers, government entities, and businesses—have been separately or together removing tangled masses of nets before they negatively impact wildlife, coral reefs, and beaches.

Researchers are also delving deep into what happens when wildlife—especially seabirds, turtles, and many other animals— ingest plastic.

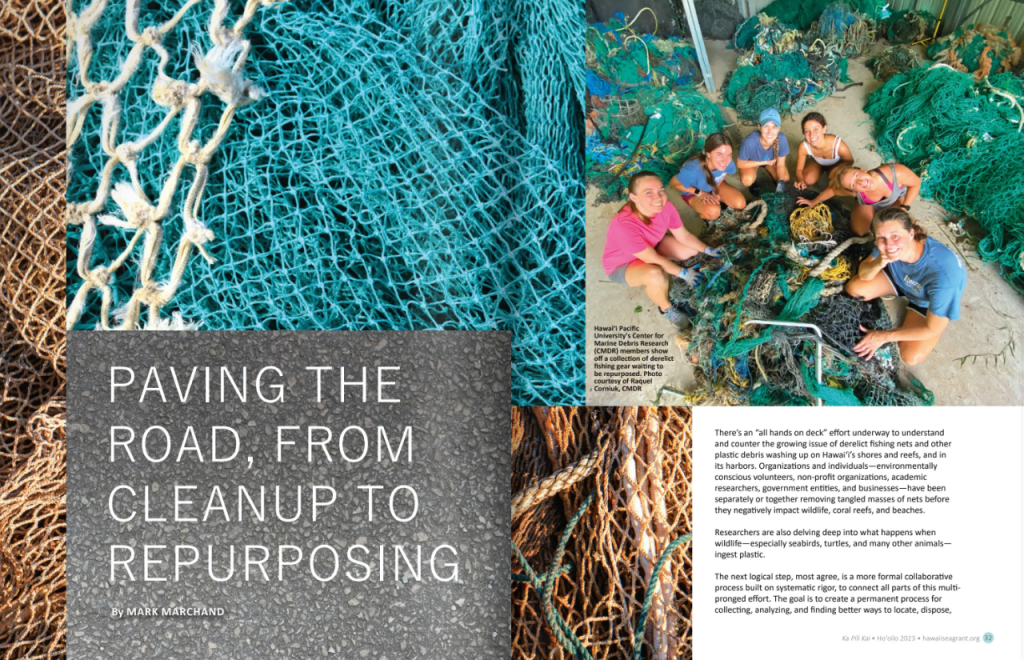

The next logical step, most agree, is a more formal collaborative process built on systematic rigor, to connect all parts of this multi- pronged effort. The goal is to create a permanent process for collecting, analyzing, and finding better ways to locate, dispose, or recycle plastic waste before it fouls the landscape or is ingested by wildlife. Hawaiʻi Pacific University (HPU) and others connected to academia and research established the Center for Marine Debris Research (CMDR) in 2018 to help expand and coordinate efforts of those who were already working on the issue. As co-director of HPU’s CMDR and a National Institute of Standards (NIST) research biologist, Dr. Jennifer Lynch seeks an end-to-end procedure that starts with advanced detection of the abandoned nets.

The key, she says, will rest on six scientific pillars: biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, political science, and economics. Lynch and others are already connected with leaders and experts in each area to gain their input.

“Studying any one facet of this problem without considering the five others doesn’t help us,” she explains, citing biology as an example of one area which will help researchers understand how ingesting plastic affects wildlife. “We need a holistic approach to understand and solve this problem. It’s not going to take a single solution.”

The scope of the problem is huge. On an annual basis, hundreds of tons of damaged and abandoned nets become entangled in Hawaiʻi’s reefs or wash up on shores. In one clean-up trip in 2021 around Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, northwest of the main Hawaiian Islands, a giant 50-ton mass of large plastic waste was recovered. Most of the waste was plastic fishing nets of all sizes, shapes, and colors.

Regulation and analysis of the abandoned nets can be challenging given that the majority are not locally generated. Research conducted by Lynch and others has shown the majority of discarded nets originated in Asia, making it more difficult to educate those responsible for casting off old or damaged nets.

Simultaneously, to tackle the nets already afloat, Lynch and partners launched a “bounty” program. Commercial fishers are paid to collect derelict fishing nets before they reach Hawaiʻi. NOAA’s Marine Debris Program, the Hawaiʻi Longline Association, and Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources have provided funding for this effort.

Beyond this program, CMDR still plans a permanent, multi-faceted process for finding and removing the nets, fueled by a $3 million grant from the National Sea Grant College Program, and in coordination with the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program. CMDR has established a seven-step process now under development: detection, documentation, removal, transportation, storage, sorting, and repurposing. New detection techniques, for example, could involve regular satellite imagery, while new documentation programs will create databases with the chemical makeup of nets from different areas, as well as new data modeling to predict the arrival of derelict nets. CMDR has already assembled one of the largest known databases on retrieved nets, with over one million entries and counting.

“From cradle to grave, we want to follow each little piece of this waste and see where it ended up. One of the purposes of our database is to get people to talk to one another and better coordinate their efforts,” says Lynch.

Nets to Roads

Perhaps the most interesting stage of this process, according to one of Lynch’s former students and now current CMDR employee Cara McGill, is recycling instead of dumping nets in landfills or burning them. Along with co-workers and several partners, they’re hitting the road for the solution. For the last two years, as part of her master’s degree work, McGill has been researching and helping test the conversion of waste net plastic into a useful part of asphalt used to re-pave roads. The program is called “Nets to Roads.”

Currently, a special type of “virgin” plastic is imported from the continental United States in the form of plastic pellets designed to improve the performance of road asphalt. “We realize shipping it in is expensive, though, and generates more greenhouse gases in the process. We hope to prove we can use recycled plastic from the derelict nets here to replace that product,” says McGill.

McGill will soon join with CMDR co-workers and partners at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation to analyze how effective recycled net plastic is for a section of Fort Weaver Road in Ewa Beach on Oʻahu. In 2022, workers repaved the road with three different plastic pellet mixes, using the equivalent of 195,000 discarded plastic bottles. One third of the road-paving project used all-recycled plastic; the second third used a 50-50 mix of recycled plastic and imported virgin plastic; and the final control portion used 100 percent of the commercially obtained plastic additive. Researchers will simulate rain on all three parts of the road to determine whether plastic occurs in any roadside runoff. They’ll also analyze the strength of all three road segments to establish whether the section using all recycled plastic remains as strong as traditional asphalt paving in Hawaiʻi’s unique environment.

Biological Effects of Plastic

As Lynch and her collaborators work toward better, multi-partner processes, scientists like HPU’s Dr. David Hyrenbach are learning how ingesting plastic affects animals such as seabirds and turtles. His approach involves three areas: analyzing the stomachs of deceased predator birds like albatrosses and petrels to find evidence of plastic; studying offspring to learn how ingested plastic affects avian growth and overall health; and finding how certain chemicals involved in plastic manufacture, such as a compound that protects plastic from ultraviolet radiation, find their way into areas of a bird’s body, besides the stomach.

“Right now, we’re focusing on pieces of plastic that range from 0.1 millimeters to 5-20 millimeters, because that’s the size of matter most of the birds swallow, although some large birds can eat something as big as a toothbrush,” Hyrenbach explains. “What we’re hoping to establish are some trends that will help us understand what plastic is doing to these animals … We just don’t know the long-term impact.” Even though Lynch, McGill, Hyrenbach and others are striving for far-reaching, complex solutions, they maintain a simple vision, coupled with the recognition that the current recycling and research are important first steps. “My passion is to simply find ways to use this waste for the betterment of society,” McGill says. Hyrenbach adds, “We know we can’t wait for a perfect solution to these problems; we know there are some steps we can and are taking now.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE