The science of tsunamis has expanded in leaps in recent decades. From advances in detection and alert systems to coastal inundation modeling and mapping, we now know more about the seismic forces that trigger tsunamis and can forecast how tsunamis will flood distant coastlines hours before the waves arrive.

However, successful preparation for a tsunami still occurs at the community level, preparing infrastructure for the unique destructive forces that occur and educating people on how to react and get to safety. While there have been several tragic tsunamis in the recent past across the globe, we are learning from these events and building stronger, more resilient communities.

Hilo on Hawai‘i Island is often referred to as the “tsunami capital of the United States” due to the shape of its bay that magnifies the height of tsunamis, making the town more susceptible to damage. A series of deadly tsunamis destroyed downtown Hilo in the mid-twentieth century, and it was that experience that spawned the early tsunami alert system organized by UNESCO, and the International Oceanographic Commission, and used by countries around the Pacific Rim.

While we have learned much since the tragedies in Hilo, other more recent events have shaped our knowledge of tsunamis, including the 2004 tsunami that killed more than 200,000 people in the Indian Ocean basin; a deadly 2009 tsunami that hit the islands of American Samoa, Independent Samoa, and Tonga; and the massive 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated northern Japan.

While these tragic events will be remembered in these communities for generations, they also provide lessons for other coastal communities facing tsunami risk. There are currently efforts underway in Hawai‘i to raise buildings standards and improve community planning and design to mitigate the impacts of tsunamis in high-risk zones. More communities are also taking steps to prepare for when the next tsunami sweeps ashore using community-level, neighbor-to-neighbor education and response networks.

Deadly Tsunamis Strike Hilo

An unassuming public clock on a green metal pole stands on the bayfront in Hilo on Hawai‘i Island. The clock’s hands are forever frozen at 1:04 a.m., a memorial to the moment when a tsunami roared into Hilo Bay in the early morning hours on May 23, 1960.

A succession of eight waves generated by a massive earthquake off the coast of Chile 15 hours earlier slammed into downtown Hilo, with some waves as high as 35 feet. The water washed through the entire downtown area, killing 61 people and destroying hundreds of homes and buildings.

The clock was found in the rubble and refurbished, but its hands were left fixed at the moment it was swept away along with the rest of Waiākea Town, a mostly Japanese neighborhood formerly located on the bayfront.

Dr. Walter Dudley, an oceanography professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo and the founder of Hilo’s Pacific Tsunami Museum, said the 1960 tsunami in Hilo had an enormous impact on the community, not just in the physical devastation and loss of life, but through the changes that came to the town in the aftermath. He said, in some ways, the tsunami upended the entire social and ethnic structure of the town.

“The various parts of the population in Hilo had been intentionally segregated by the sugar planters because they were afraid of labor unions. They’d kept the Japanese in their own village and the Filipinos in their own village—but the planters were losing that battle,” said Dudley. “After the tsunami, these groups all worked side by side to clean up and recover. That really brought the different communities together.”

The 1960 tsunami also changed Hilo’s approach to development and building design.

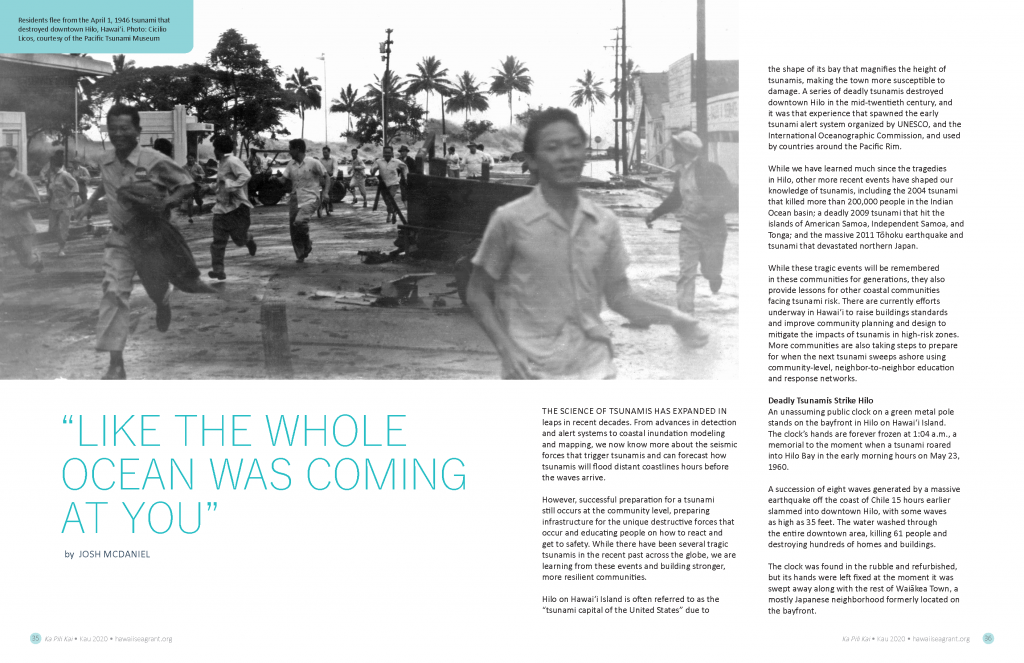

A previous tsunami had struck Hilo in 1946, killing 159 people and destroying the bayfront. The community had rebuilt on the same spot only to see the efforts swept away once again in 1960.

After the 1946 tsunami, Hilo designated a section of the bayfront as a buffer zone where no businesses could be built. The highway along the waterfront was raised as a barrier, and a warning system with sirens was put in place. After the 1960 tsunami, Hilo launched the even more ambitious Project Kaiko‘o, which created a broader oceanside greenbelt buffer zone of lagoons, gardens, and recreational facilities designed to protect inland areas by absorbing the impacts of future tsunamis. The park was completed in 1965 and named the Wailoa River State Recreation Area.

Hilo emergency management officials created a new warning system and evacuation plan. They also began a renewed campaign to educate the public about tsunamis and raise awareness about what to do when the tsunami warnings sounded. The state of Hawai‘i also designated the month of April as Tsunami Awareness Month and developed evacuation drills, training exercises, and an educational campaign for schools, harbors, and beachfront hotels throughout the islands.

The 1946 tsunami in Hilo prompted the U.S. and other countries of the Pacific Rim to create a network of seismometers, tidal gauges, and ocean buoys designed to detect the undersea tremors that generate tsunamis. That system was expanded after the 1960 Hilo tsunami. When a tsunami is detected, the buoys relay data to NOAA’s Tsunami Warning Centers around the Pacific, and these centers then send this information to the civil defense organizations of countries that face potential impacts.

Yet, science and technology have limits when it comes to preparing vulnerable communities located near hotbeds of seismic activity, where quakes may trigger tsunamis that strike within minutes. In these places, it is education and training at the community level on how to react and get to safety that can make the difference.

The 2009 Tsunami on American Samoa

Early in the morning on September 29, 2009, Pete Gurr was driving with his family from his home in the mountains on American Samoa down to the coast when he felt a strong earthquake.

Gurr, the deputy director of the Department of Agriculture for the island at the time, had attended a training session in tsunami response for government officials only weeks beforehand. He immediately knew the strength and duration of the quake were warning signs of a potential tsunami.

As Pete and his wife and daughter approached the coast, there were boulders that had fallen on the road from the earthquake, preventing cars on the mountainside from driving in the proper lane. As they passed the boulders, Pete noticed the ocean had gone flat (no waves), and seconds later, the water began receding as he yelled out to his family, “It’s here!” referring to the approaching tsunami.

“We saw the water going out like the waves were reversing,” said Gurr. “It made a roaring sound that was really spooky. The reef just dried out. Then, we could see the ocean getting higher and higher building up about a mile out, like a big wall going up, probably a hundred feet plus.”

Pete began honking his horn to alert the people in the village of Afao while a young man started ringing the village bell to alert all to the imminent danger. Pete drove his truck as far back from the shore as he could, and his wife and daughter — along with the villagers — began running up the mountain to safety. Pete and Senator Fuamatu, as well as the village aumaga (village youth), directed everyone to evacuate to higher ground. Those on the lower part of the mountain watched in horror as the ocean completely inundated the village below.

“I tell you that water just came so fast. It was wild. It was mean. All whitewater. It wasn’t like a regular Hawaiian surfing wave,” Gurr said. “It was just a massive whitewater, like the whole ocean was coming at you.”

The tsunami was created by a large earthquake that occurred nearly midway between Samoa and American Samoa near the Tonga Trench. The ensuing tsunami killed nine people on the island of Tonga, 149 in the independent country of Samoa, and 34 in American Samoa. It was the deadliest tsunami in the Samoa region in living history.

Officials, such as Gurr, believe the loss of life on American Samoa would have been much higher without the training that the TsunamiReady program conducted on the island for teachers, school administrators, eighth-grade students, and government officials mere weeks prior to the 2009 tsunami.

“Training, training, training,” said Gurr. “I’m a hundred percent believer in that.”

Laura Kong, the director of the UNESCO IOC-NOAA International Tsunami Information Center, was one of the instructors in the training that Gurr received. She said she’s grateful he remembered one of the most important take-home messages from the course.

“If you feel the shaking and it’s strong—unlike anything you’ve ever felt—you have about 15 minutes before the first wave hits you,” Kong said. “So, just that little bit of information—really important information, valuable information—made a big difference and went a long way to saving lives.”

“On one side we can have all the technology, all the instruments and the detections, all these deep ocean buoys, and these seismometers, GPS, satellites, whatever you like, but if you are in a situation where you have a local threat, like in American Samoa, your warning sign is the natural warning sign—the shaking from the quake, the water receding,” Kong said. “You don’t necessarily wait for an official warning and the sirens to sound. You have to be aware and know that tsunamis can occur and self-evacuate.”

Gurr said that in many villages, the children recognized the natural signs because of the training they received, and the evacuation drills they practiced in school.

“In certain villages, it was the kids who told people to run,” Gurr said. “The kids saved peoples’ lives too.”

Gurr recalled seeing Aveao Faausu Fonoti, the mayor of Amanave, running through the village with a megaphone urging everyone to evacuate. Due to actions of officials like Gurr and Fonoti, as well as other brave villagers, there were no casualties in Amanave despite destruction of 80 percent of its buildings.

Fonoti later received the 2010 Community Resiliency Leadership Award at the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center at the University of Hawai‘i for his handling of the 2009 tsunami.

Gurr says that people on American Samoa don’t sit around and wait for help from the federal government. That was shown right after the tsunami when they began clearing roads and rebuilding even before FEMA arrived.

“We don’t wait. Right afterwards, we had out our chainsaws and our machetes, and we’re clearing,” Gurr said. “The feds arrived, and they couldn’t believe it. They said, ‘Where’s the damage?’”

That same can-do community spirit has transitioned into preparing for the next tsunami. American Samoa has established a 24/7 National Earthquake and Tsunami Warning Center and built an Emergency Operations Center to support disasters. They’ve created evacuation maps and signage designating hazard zones and safe zones. In addition, the government upgraded its warning dissemination systems to include island-wide sirens and an instant messaging system for local officials, churches, schools, NGOs, and businesses.

“It’s never good when something happens like what happened on American Samoa—34 people perished,” said Kong. “But there were amazing stories of heroic acts that can be really good lessons learned for us here in Hawai‘i, and everywhere in the U.S. that is at risk of experiencing a tsunami.”

Remaining Vigilant

Over the past few decades, Walter Dudley and his team from the Pacific Tsunami Museum have conducted over 500 tsunami survivor interviews from a dozen countries. They traveled to Thailand, Sri Lanka, India, and the Maldives after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which slammed into 11 countries and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

“There were villages that were completely wiped out,” he said. “The only survivors were the fishermen who were out fishing—how do you recover from that?”

Dudley said the interviews have been a powerful way of getting people to understand how they were at risk from tsunamis and what they needed to do to prepare.

“When you hear the message from somebody from your own community, not by some central government agency telling you information, which is sometimes not totally relevant to your own situation, you can pay more attention,” he said.

In the same way, preparedness and response are also most effective when organized at the community or neighbor-by-neighbor level. Dudley described one preparedness program that was developed in Thailand.

“The villages would say, ‘if daddy’s out fishing, who’s going to take care of grandma?’ So it would be uncle so-and-so or auntie, and they’d have a whole list made up and they actually did full village evacuation drills and they went through the process and, Oh boy, what a difference it made,” Dudley said. “I think they’re among the best prepared communities everywhere.”

As our knowledge of tsunamis evolves and science and technology provide us with the ability to detect tsunamis and predict their impacts, we need to remember that one of the most powerful tools in any emergency is community and the capacity of people to work together and look out for those who can’t look for themselves.

Hawai‘i will always be at risk from tsunamis, but we are now better prepared than ever to keep our communities safe. But preparedness is a continual process, and we must never drop our guard.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE