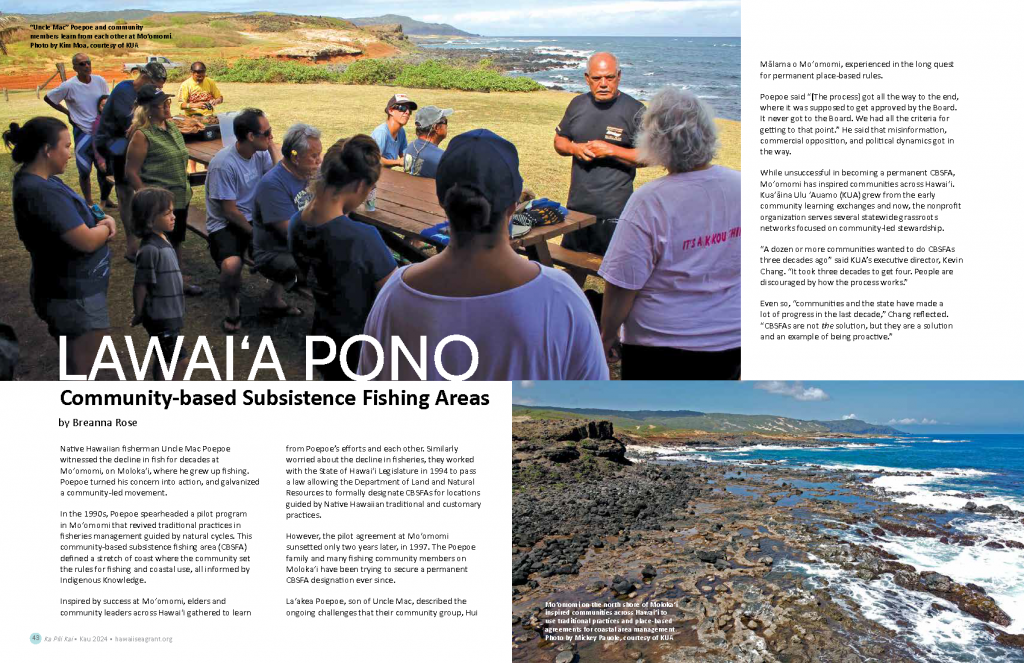

Native Hawaiian fisherman Uncle Mac Poepoe witnessed the decline in fish for decades at Moʻomomi, on Molokaʻi, where he grew up fishing. Poepoe turned his concern into action, and galvanized a community-led movement.

In the 1990s, Poepoe spearheaded a pilot program in Moʻomomi that revived traditional practices in fisheries management guided by natural cycles. This community-based subsistence fishing area (CBSFA) defined a stretch of coast where the community set the rules for fishing and coastal use, all informed by Indigenous Knowledge.

Inspired by success at Moʻomomi, elders and community leaders across Hawaiʻi gathered to learn from Poepoe’s efforts and each other. Similarly worried about the decline in fisheries, they worked with the State of Hawai‘i Legislature in 1994 to pass a law allowing the Department of Land and Natural Resources to formally designate CBSFAs for locations guided by Native Hawaiian traditional and customary practices.

However, the pilot agreement at Moʻomomi sunsetted only two years later, in 1997. The Poepoe family and many fishing community members on Molokaʻi have been trying to secure a permanent CBSFA designation ever since.

Laʻakea Poepoe, son of Uncle Mac, described the ongoing challenges that their community group, Hui Mālama o Moʻomomi, experienced in the long quest for permanent place-based rules.

Poepoe said “[The process] got all the way to the end, where it was supposed to get approved by the Board. It never got to the Board. We had all the criteria for getting to that point.” He said that misinformation, commercial opposition, and political dynamics got in the way.

While unsuccessful in becoming a permanent CBSFA, Moʻomomi has inspired communities across Hawaiʻi. Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA) grew from the early community learning exchanges and now, the nonprofit organization serves several statewide grassroots networks focused on community-led stewardship.

“A dozen or more communities wanted to do CBSFAs three decades ago” said KUA’s executive director, Kevin Chang. “It took three decades to get four. People are discouraged by how the process works.”

Even so, “communities and the state have made a lot of progress in the last decade,” Chang reflected. “CBSFAs are not the solution, but they are a solution and an example of being proactive.”

Twenty years after the law passed, in 2015 the state designated Hāʻena on the north shore of Kauaʻi as the first permanent CBSFA. This milestone paved the way for others. The fishing community of Miloliʻi on the southwest coast of Hawaiʻi Island became the second CSBFA in 2022, and in 2024, the remote area of Kīpahulu in east Maui became the third and most recent community designated.

Dr. Mehana Vaughan, an associate professor of environmental management at the University of Hawaiʻi and faculty with the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program, grew up close to Hāʻena and recalled what became a watershed moment for CBSFAs. While pursuing her PhD at Stanford University, she documented the Hā‘ena community’s CSBFA undertaking.

Dr. Vaughan remembered the long, participatory process to gather input for place-based fishing rules. It began with backyard luʻau and talks with fishing families, led by Hui Makaʻāinana o Makana. The Hui connected with groups across Kauaʻi, from windsurfers and kite surfers to commercial operators and fishers, to broaden community engagement.

Today, the Hāʻena CBSFA rule package, like Miloliʻi and Kīpahulu, bans fishing for commercial purposes and particular gear. CBSFAs allow anyone to fish using specific methods, such as fishing poles, to take only what is needed. Rules are based on traditional subsistence practices and the principle of lawaiʻa pono: to fish righteously. Harvesting limits and managed rest areas allow for species repopulation. Like a neighborhood watch for the ocean, Makai Watch brings together the state, nonprofit organizations, and volunteers to report and enforce the agreed-upon rules.

Today, the data is clear: Hāʻena fishery’s health is improving, even in the face of disruption.

Researchers from the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa assessed the environmental impacts through a five-year review, and the results showed that the fish are fatter and the fisheries are healthier. Residents also observed that the fish were coming back closer to the shore, as elders remember from when they were young.

“2016 and 2017 showed a statistically significant increase in fish biomass,” says HIMB researcher Dr. Kuʻulei Rodgers about Hāʻena. “Overall, across all five years showed an increase and that the CBSFA is working.”

However, in 2018, an extreme storm flooding event and landslides from unprecedented rainfall closed access to the north side of Kauaʻi. Storm run-off affected the area’s water quality and marine life, leading to coral bleaching, plummeting biomass, and a mass die-off of sea urchins.

With increasing climate change impacts like severe weather events, adaptive management approaches based on traditional practices, like those used in CBSFAs, become critical. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, Indigenous Knowledge is crucial to addressing the threat of climate change and protecting the world’s remaining biodiversity.

Still, CBSFAs continue to face opposition. In the 2023 legislative session, a bill proposed sunsetting all CBSFAs and repealing the Hāʻena designation. There was overwhelming testimony against the bill, but the Hawaiʻi Fisherman’s Alliance for Conservation and Tradition (HFACT) agreed with the measure’s proposal for time limits on CBSFAs.

Phil Fernandez, president of the nonprofit fishing alliance, said the group wants to promote accountability. Fernandez and HFACT executive director Edwin Watamura note that the alliance shares the same concerns about a healthy habitat and, therefore, a healthy fish population. However, they said it is crucial to implement managed areas correctly, or the state should re-evaluate and repeal the designations.

Fernandez described “successful implementation” as a written management plan, monitoring, enforcement, and long-term succession to avoid losing momentum when an individual activist retires.

“There is strong feeling in the fishing community that they are under attack by conservationists,” Watamura said, emphasizing that most fishers comply with rules and care for the ocean. He shared that the perception of exclusive fishing areas and “vilification bothers fishers a lot.”

Edward “Luna” Kekoa, the ecosystems program manager with the state’s Division of Aquatic Resources, underscored the importance of education and outreach.

“Fishing is our culture here,” Kekoa said. “Our role as the managing government agency is to find that balance between the science and people who use the resources.”

Kekoa shares that when open dialogue occurs, win-win solutions can emerge. During public hearings for the Kīpahulu CSBFA, fishers voiced concerns about the proposed Kukui Bay Sanctuary because it was a main shoreline access point. After several meetings, the groups compromised to redesign the boundaries for safe access while protecting the vital nursery habitat.

Ultimately, CBSFAs are more than a law or set of rules. They represent one pathway to support a broader vision shared by many: the long-term health of Hawaiʻi’s fisheries and people.

“It’s a tool we’re testing to achieve the vision of overall ahupuaʻa management through a traditional lens with a modern spin,” said Emily Cadiz, who, with Billy Kinney, is part of the next generation of leaders stewarding Hāʻena. Kinney added that the purpose of traditional management from the mountains to the ocean is “holistic and generational well-being.”

Elders like Poepoe have dedicated their lives to this vision. Alongside emerging leaders and a collective across Hawaiʻi, they are using CBSFAs to help chart a course for communities to care better for their ancestral places–and each other–for generations to come.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE