In the 2023 run up to New Year’s Eve, Hawai‘i saw a bounty blow in from across the Pacific, the result of a difficult negotiation. The local fleet’s catch limit on ahi had been increased. There would be no New Year’s price spike for the fish that is an integral part of New Year’s celebrations all over the islands. Poke, sashimi, and ahi collar all found their way onto local tables to ring in 2024 without breaking the bank. Residents and visitors alike could dig into their New Year’s bowls of poke with celebratory abandon.

Red is good luck at the new year, a symbol of prosperity and fortune, per Asian cultures. In late 2023 red-fleshed ahi saw a catch limit jump from 3,554 metric tons to 6,554 metric tons for the season. But this late-year increase did not come by luck; it came by a conservation and management measure negotiated into the early morning hours on December seventh in Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands.

The negotiating parties were the members of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). The WCPFC includes twenty-five members ranging from geopolitical giants like the United States and China to tiny island states like Vanuatu, and is organized on a tripartite structure: a Scientific Committee, a Technical and Compliance Committee, and its regular session—the decision-making body—the member states.

A Local Staple

Hawai‘i’s local tuna longliners account for only two percent of global tuna catch, and decisions like WCPFC’s can seem remote, even as they are critical to the local fleet. The larger fishing area Hawai‘i is included in, and which WCPFC helps manage, rates as a close second to the most sustainably fished catch areas in the world, according to the 2022 UN ‘State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture’ report.

But what does this mean to local people picking up fish marked “Auction Fresh”? As both our most economically productive, and regulated, commercial food industry, the longline fishery is complicated and not likely much on the minds of residents when making daily seafood purchase decisions.

Eating fish is part of Hawaiʻi’s culture. Statewide on-average consumption of seafood is two to three times higher here than any state in the U.S., our hungry mouths taking in more than 4,000 metric tons of seafood annually between 2007 and 2016. This includes seafood from all sources; locally caught, shipped in, fresh, and prepared.

The Honolulu-based longline fleet of about 140 vessels contributes perhaps the most beloved component of that consumption: fresh fish for our sashimi, poke, and searing on our grills. The local fleet represents a drop in the bucket of nationwide commercial fleet landings, but its premium fish is worth about $125 million annually.

The fleet produces 95 percent of U.S. bigeye tuna landings, as well as 50 to 60 percent of yellowfin tuna and swordfish landings. And for as much of that valuable fish as we eat here, the fleet pulls in enough fish to export 20 percent of the annual catch to the continental U.S.

Hawaiʻi Longline History

Today’s Hawaiʻi longline fishing industry began with immigrant Japanese fishermen who were flourishing in the islands by 1900. After fulfilling the plantation contracts that drew them to the islands, skilled Japanese commercial fishers left the fields and fell back on their previous fishing competence. Advances made to Japanese fishers’ traditional sampans were the technology that cemented ethnic Japanese dominance over the local fishing industry.

By 1905, traditional Japanese vessels began to be motorized, and the wooden motor-sampan aku and tuna boats became state of the art, modified from their original design to ply Hawaiian waters. These advances powered a robust local fishing industry into the 1930s. But war with Japan arrived and changed everything. Much of the fleet was impounded by U.S. military authorities due to its ethnic Japanese associations. Martial law eventually allowed limited commercial fishing to supply local wartime food needs using longline tackle developed centuries prior in Japan.

After the war, fishing remained impacted and failed to immediately regain the economic prowess it saw prior to the conflict. Markets were curtailed by supply as the species sold catered to local ethnic tastes. By the early 1960s the U.S. Department of the Interior designated Hawaiʻi’s fishery as “dying.” Insofar as it remained, it was dominated by skipjack (aku) destined for the Coral Tuna cannery. Historian Samuel G. Pooley designated 1975 as the low point for the local commercial fishery. At this time foreign factory ships, especially Soviet, were cleaning out the high seas, and state- and territory-adjacent nearshore waters.

Enter the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, signed into law in 1976 to protect U.S. fisheries from foreign exploitation, and part of the legal management framework system Hawaiʻi’s longliners participate in today. It is a complex system including the WCPFC, the joint federal and state Western Pacific Regional Management Council (WP Council), NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, and NOAA scientists. These groups work to manage the commercial fleet and fisheries that make fresh ahi poke available—designating their gear, allowable fishing grounds, catch size and type, and need for onboard observers.

Fish for the Future

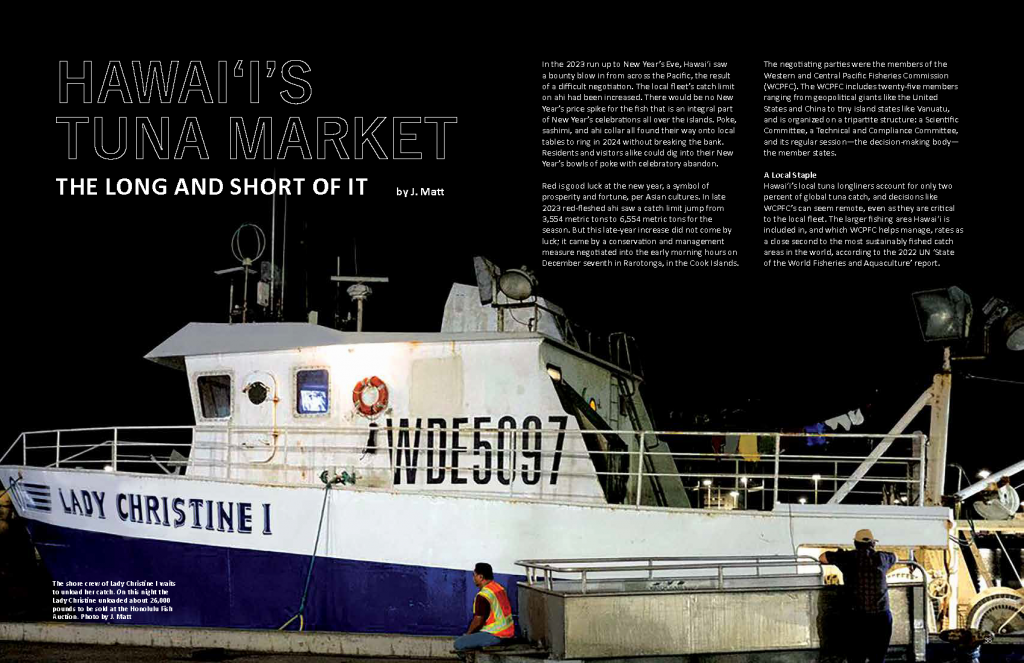

Much of that poke stock passes through the Honolulu Fish Auction, beginning in the early morning hours as it is unloaded from longliner vessels onto Pier 38 in Honolulu. Ahi, aku, tombo, billfish, other pelagic species like mahi mahi, opah, and monchong, and the bottomfish that are managed by WP Council, all make their way into the wholesale market at the Honolulu Fish Auction.

Run by the United Fishing Agency since 1952, it is the only daily auction in the U.S. and runs on the Japanese model of sales of individual fish rather than gross catch weight from a vessel. Each tuna is ascertained as sellable or rejected by an auction employee who cuts a bit of flesh from the tail of a tuna, checks its texture, and smells it. The auction presents a point of control in response to labor concerns on the Hawai‘i fleet’s vessels, which are principally crewed by foreign national sailors.

So, back with our bowl of fresh, never frozen, local fish; should we be concerned about eating the national dish of Hawai‘i? Like everything, it’s complicated. Global warming will affect pelagic species, likely by their migration as ideal habitat temperatures shift with warming currents. Labor rights are a fraught issue all over the world.

Perhaps understanding that everything we do as human consumers has impacts on our planet is the best way to grapple with these questions and our bowls of poke. Dr. Ryan Rykaczewski, leader of the NOAA Pelagic Research Program at the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, put a fine point on it. When speaking about the consequences of commercial fishing, Rykaczewski commented that we cannot believe even the best managed fisheries on the planet to be free of consequences.

In May 2017, the United Nations published an article by Jake Rice, chief scientist emeritus of Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans. In it, Rice widens the view, “There needs to be a serious dialogue to determine what types of alterations in marine and coastal ecosystems are sustainable.”

Regarding management of the fish species we like to eat, whether as a part of our culture, or just because we like the way they taste, Rykaczewski said, “The target is not no impact; the target is some sustainable impact that can continue on for generations.” In other words, stewardship demands that we make difficult, complicated decisions, in swiftly changing times.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE