Ghosts haunt the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. They glide in with the currents and tides, from all around the North Pacific Ocean. They destroy coral reefs and ensnare seals, sea turtles, and other endangered animals. They foul the beaches, present a hazard to boats, and cost millions of dollars to exorcise.

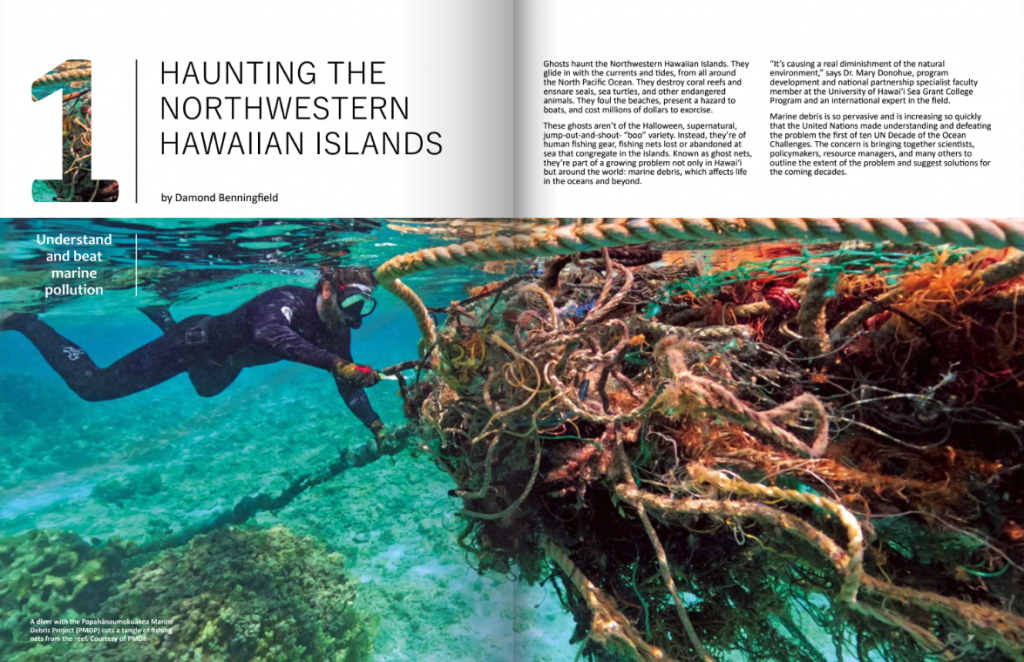

These ghosts aren’t of the Halloween, supernatural, jump-out-and-shout- “boo” variety. Instead, they’re of human fishing gear, fishing nets lost or abandoned at sea that congregate in the islands. Known as ghost nets, they’re part of a growing problem not only in Hawaiʻi but around the world: marine debris, which affects life in the oceans and beyond.

“It’s causing a real diminishment of the natural environment,” says Dr. Mary Donohue, program development and national partnership specialist faculty member at the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program and an international expert in the field.

Marine debris is so pervasive and is increasing so quickly that the United Nations made understanding and defeating the problem the first of ten UN Decade of the Ocean Challenges. The concern is bringing together scientists, policymakers, resource managers, and many others to outline the extent of the problem and suggest solutions for the coming decades.

The great bulk of marine debris consists of plastics. “Any type of plastic you’ve ever used, it’s out there, and more than 80 percent of it comes from land,” says James Morioka, chief scientist and executive director of the non-profit Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP), which collects ghost nets and other nasties from the monument twice a year.

A 2022 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine said that about nine million tons of plastic debris enters the ocean every year, “the equivalent of dumping a garbage truck of plastic waste into the ocean every minute.” If the current upswing in plastic production continues, the report said, the amount could reach almost 60 million tons by 2030. And since plastic is designed to be durable—no one wants their water bottle to spring leaks, after all—“most of the plastic ever produced since the beginning of time is still around,” says Donohue.

Plastic swept into the oceans by rivers, rains, and other avenues can float for years or decades, forming “garbage patches” that are carried around the world by currents. The largest is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which covers hundreds of thousands of square miles.

The Pacific patch is circulated by the North Pacific Gyre, a series of currents that swirl clockwise around the Hawaiian Islands. The northwestern islands are close to the northern boundary current, so debris from the garbage patch sweeps across them.

“The islands are uninhabited, yet this remote seascape is plagued with debris of all sorts, especially fishing gear,” says Mark Manuel, Pacific Island regional coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program. “The islands act like a sieve or a comb. It’s pretty remarkable, in a bad way.”

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, which stretch about 1,250 miles from Honolulu, are contained within Papahānaumokuākea, the largest marine protected area in the United States and one of the largest in the world. It covers more than 580,000 square miles and is home to more than 7,000 species of birds, mammals, and other life, a quarter of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

Papahānaumokuākea, which is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a place of special significance to Native Hawaiians, says Kaʻehukai Goin, a graduate student at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, who has participated in two debris removal expeditions to the islands. “It’s a place of the gods; our islands and our genealogy extend from there. So to our people, it’s the concept of mālama ‘āina—to care for the land, the air, the water. You always take care of the ‘āina, because it takes care of you.”

Taking care of the islands isn’t easy. Scientists estimate that more than 50 tons of debris accumulate there every year, with a total of almost a million pounds currently stacked up on the beaches or in the adjoining lagoons and shallows.

On shore, the problem is plastics: bottles, bottle caps, cigarette lighters, sandals, sneakers, umbrella handles, toothbrushes, combs, helmets, toilet seats, and many other products. “I’m a toy collector, and I’ve come across several little green army men up there,” says Morioka, who estimates he’s spent a total of three years in the islands. “I haven’t seen them in stores in probably 20 years, but I see them on shore. That’s pretty incredible.”

Birds and other critters become entangled in the debris and can’t escape. Others eat eroded bits of plastic, creating additional problems.

“It’s appalling how much of this sea turtles are eating,” says Dr. Jennifer Lynch, a research chemist and co-director of the Hawaiʻi Pacific University Center for Marine Debris Research. “We’ve seen them with up to 200 grams in their stomachs, like half a soda bottle full of plastic. They feel full, but there’s no nutrition. That reduces growth, so they’re more likely to be eaten by others.”

In addition, Lynch says plastics are “a cocktail of many, many different chemicals.” Studies have shown that ingesting them can affect reproduction, the quality of eggshells, hatchling growth rates, and other health aspects. And animals don’t have to eat the plastics directly to suffer the effects, Lynch notes. The chemicals can be ingested by everything from plankton to fish, then are transferred up the food chain.

By far the biggest problem in the islands, though, is ghost nets. They come from trawlers, deep-sea tuna fishing, and other operations. They often form tangled, twisted balls that can weigh tons.

Morioka got interested in marine debris when, while studying monk seals in the monument, he found an 11.5-ton net ball that contained two dead sharks, numerous turtle shells, and a tree. “I had a vendetta against that ball,” he says.

Almost none of the nets come from Hawai‘i. Instead, they’re carried by the currents from Japan, Asia, North America, Central America, and from fishing operations far from any shore, says Kevin O’Brien, founder of PMDP and a former NOAA employee. “The monument is highly protected; there’s no fishing allowed at all. So it’s not coming from Hawai‘i. I suspect that some of it is lost gear, and some is intentionally thrown overboard. There’s very little accountability out there in the mid-Pacific.”

Much of the gear consists of gillnets, walls of nets suspended from buoys that can stretch for hundreds of yards. Other debris comes from abandoned fish aggregating devices (FADs), which are comprised of nets, sensors, and GPS systems. They’re set adrift to snare tuna. They amass their own ecosystems of smaller fish, then alert their owners when enough tuna congregate in the nets. The systems are cheap enough that it’s sometimes less expensive to abandon them than to retrieve them if they don’t bring in enough tuna. The GPS trackers can be switched off, so it’s impossible to determine their origin.

FADs and the other nets can ensnare humpback whales and other marine mammals offshore, carry invasive species and hazardous chemicals, and even pose a hazard to navigation. One study reported that similar nets off the coast of South Korea had entangled the propellers of hundreds of navy vessels.

Most significantly, they devastate coral reefs as they move into island waters. “It just bulldozes these habitats,” says Lynch. “One of these balls snags on a reef, smothers it, kills it. Then another wave comes along and pushes it farther toward shore and it does the same thing to the next patch.”

“It really shakes you inside to see the damage these nets can do,” adds Manuel. Return inspections of damaged sites show that the reefs don’t grow back.

In the late 1990s, NOAA launched a clean-up campaign to clear the nets from the monument. It staged one trip into Papahānaumokuākea per year, then cut back to one every three years, then dropped out completely. By then, O’Brien had started PMDP, which today ventures into the monument twice a year, with a hoped-for increase to thrice, often enough to clear the backlog.

During the most recent trip, in November 2022, the crew spent 30 days at sea and collected more than 53 tons of junk, including 48 tons of ghost nets—32 from the reefs and 16 from the beaches.

Recovered debris has been repurposed in several ways, Morioka adds. H-Power has produced electricity from some of it. The Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation has tested an asphalt mixture that incorporates ground-up nets, and will become the main beneficiary of the debris in the years ahead. Others have made skateboards, sunglasses, building blocks, and even art.

For example, Ethan Estess, a surfer, marine scientist, and artist who splits his time between Oʻahu and Santa Cruz, California has created artworks using tons of rope from derelict fishing lines, including a mural in a Waikīkī resort crafted using debris from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. “I’m trying to use art as visual storytelling to inspire change,” he says. “I want to draw people in with something that’s eye-catching, so they say ‘Cool!,’ but then they look deeper and get an understanding of the problem.”

Ultimately, though, clean-up efforts may only be applying a bandage. “It’s like cleaning up after a car wreck; the damage has already been done,” notes Lynch. “We need to prevent the damage in the first place.” This perspective is acknowledged in the framework of the UN Decade Challenge, providing an avenue for recognition of the plastics issue with an eye to addressing their input, not just the resulting debris.

NOAA and other agencies have proposed many steps to control the fishing net problem: attaching barcodes to every net, requiring fishers to weigh their equipment in and out with each trip, or paying to retrieve derelict gear. So far, however, “nothing has stuck,” says Morioka.

“I hope that one day [PMDP] won’t have to exist,” Goin says. “But it’s a process. We’ve come a long way since my first time in Papahānaumokuākea. There’s a lot more awareness, and that’s where we can make a difference. We want people to be more aware of what’s going on.”

That may someday exorcise the ghosts that haunt the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE