Hawai‘i Senator Glenn Wakai was in a Zoom meeting in late January when he noted a kink in the islands’ renewable energy plans. The state’s only coal-fired power station was shutting down in September 2022. However, solar power projects replacing the plant’s 180-megawatt generation were delayed six months to a year.

The Hawaiian Electric Company (HECO) somehow needed to source enough renewable energy to feed the grid. The whole process would include time-consuming requests for proposals, sorting bids, picking winning contractors, requesting permits, procurement, building, and testing. And they had to do it in less than two years, during a global pandemic.

“I think HECO needs to be much faster in its interconnections,” Wakai said. “A recent HNEI study shows that unless unicorns save the day, there is a chance we are going to see blackouts in 2022.”

Just to be clear, the Hawai‘i Natural Energy Institute (HNEI) study Wakai referred to does not mention unicorns. It does say that even if HECO’s 2022 solar power and energy storage projects were on time, blackouts would still be likely.

In the Zoom energy briefing with Wakai were scientists, legislators, community leaders, nonprofit representatives, fuel industry officials, and HECO’s leaders—key people in implementing Hawai‘i’s plan to generate its electricity from 100 percent renewable energy sources by the year 2045.

Announced in 2015, the plan was the first law mandating a transition to 100 percent renewable energy in the U.S. At the time, it was the most aggressive and ambitious clean energy goal in the country. A year later, other U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI) followed suit, spurred by Hawai‘i and the Paris Climate Agreement.

Islands have good reasons to transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydroelectric, wave, and geothermal energy. Most island power stations run on diesel fuel. And because of their remote locations, islands import petroleum from distant oil-producing countries, such as Russia, Indonesia, and Libya in Hawai‘i’s case.

The result of import reliance: high electric bills and a dependence on fossil fuels. Hawai‘i’s total electric demand is the fourth lowest in the nation, but its average electricity retail price is nearly triple the U.S. average. As of 2019, the state sourced 75.2 percent of its electricity from petroleum and coal. The situation is as dire in the USAPI: American Samoa’s average residential electricity price is 2.5 times higher than the U.S. average, and Guam two to three times higher. Most Pacific Islands still source 96 percent or more of their electricity from fossil fuels.

It’s been about five years since Hawai‘i and other islands set their clean energy targets. How are they doing and what strategies have worked? And what hard lessons have they had to learn on their way to a clean energy future?

“Here we are in 2021 and just over 30 percent renewables on the HECO grid,” Wakai said from his State Capitol office in Honolulu. “In the past five years, we’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit and the most difficult years are ahead.”

The low-hanging fruit

When Hawai‘i started this journey, it made sense to pick solar energy from the gamut of renewable energy options. The state’s position relative to the equator means it enjoys more hours of sunlight all year round, compared to most mainland states.

“Renewables are also cheap now, and batteries are getting cheaper so fast,” said Dr. Michael Roberts, a professor at the Department of Economics, University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization (UHERO), and coastal sustainability faculty with the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program. “You can save money by installing a bunch of solar and batteries.”

Roberts, who runs a renewable energy research and outreach program, did just that in late 2015. He installed ten solar panels on his roof, adding to energy-efficient lighting and appliances and a solar heater he already had in his East Honolulu home. The solar photovoltaic (PV) panels convert sunlight to electricity in direct current (DC) and an inverter changes this to alternating current (AC), the most commonly used form of electricity. The solar setup paid for itself in three years and the solar water heater in about 18 months.

Because his home is grandfathered into a net metering agreement (NEM) with HECO, Roberts’ solar panels can generate power during the day, and he gets kilowatt-hours credited to his account to be used at night or anytime his family needs them.

“So, no battery,” Roberts said. The electric grid serves as his battery or backup. If his solar panels don’t generate enough power for his home after several days of overcast skies, he can receive or buy electricity from HECO.

Energy storage is important in the world of renewable energy, particularly energy that is around intermittently like sunlight, wind, the tides, and waves. Roberts’ on-grid home doesn’t need a battery, but off-grid homes do, so they can use stored energy in the evenings when there is no sunlight.

Power plants also need to store energy to manage fluctuating electricity demands. For example, in pre-pandemic times, electricity use would peak when people arrived home from work and kids from school. Stored energy helps fulfill these sudden demands.

When Hawaiʻi achieves 100 percent clean energy, it will have to be ready to store enough energy from intermittent renewables to serve these peak loads. “One scary situation is when everyone has their electric vehicle, and they come home and plug it in at the same time,” said Roberts. That’s a big draw of electricity and will test an unprepared system.

Small-scale dominance

Roberts’ home solar setup is considered small-scale solar in industry parlance. Solar panels on a Honolulu hotel are also considered small-scale. It’s those fields of solar panels generating more than 4 megawatts that are called utility scale, and they typically feed power directly to the grid. Utility-scale solar farms usually involve a Power Purchase Agreement that sells power to an electric company, which then distributes the electricity to its customers.

Hawai‘i’s renewable energy profile is dominated by small-scale solar. When the Hawai‘i clean energy target was announced in 2015, the state drew only 0.5 percent of its electricity from solar; wind energy from wind turbines was the leading renewable at 6.1 percent.

By 2019, wind had dropped to 4.9 percent and solar jumped to 10.2 percent for small-scale, and 2.5 percent for utility-scale. Biomass, or burning plants, farming or forestry waste for energy was at 2.7 percent. And hydroelectric, which uses water stored in dams or flowing in rivers to create electricity, was at 0.9 percent.

Those who follow renewable energy news in Hawai‘i may not be surprised that wind and solar farms trail behind small-scale solar. Utility-scale solar is expensive to develop in Hawai‘i, at two to three times what it costs on the continental U.S. On the island of O‘ahu, for example, land is expensive, and available land for new solar or wind farms is hard to secure.

Finally, Hawai‘i is learning that the race to clean energy can’t come at the expense of social equity. Communities have protested the Nā Pua Makani wind farm on Oʻahu’s North Shore for over ten years, saying the turbines are too close to schools and homes, are too noisy, and threaten the Hawaiian hoary bat, an endangered species native to the islands. Residents of Kahuku, a small town just a quarter of a mile from the wind farm, have said that they were not consulted before the project was approved.

Rooftops to the rescue

“If we filled up all our rooftops with solar, we wouldn’t have to use more land,” Roberts said. “Rooftop solar can preserve these valuable land resources.”

Using Google Maps, Roberts’ colleague Dr. Matthias Fripp estimated that Oʻahu’s rooftops can generate about 4,000 megawatts, enough to power the whole island. Single-family homes can provide surplus electricity to power hotels and office buildings in Waikīkī and downtown Honolulu which don’t have sufficient rooftop space to generate all of their own power.

In June 2020, Tesla announced that it would offer rooftop solar for $2 per watt, and that prices would be the same in Hawai‘i as on the continental U.S. “At this low price, and with federal subsidies, rooftop solar is competitive with utility-scale solar,” Roberts said.

So, why hasn’t this rooftop approach happened yet? Like Roberts, some homeowners are under an old program with HECO where they are not compensated for surplus power fed into the grid. Therefore, it made sense to put up only enough panels to meet their own electricity needs.

HECO’s new rooftop solar programs compensate homeowners at fixed rates; however, approvals are subject to caps. Roberts is also concerned that the fine print in these programs still offer little incentive for people to install a system that produces more energy than their own needs.

Hawai‘i’s current renewable energy system also favors households that can afford to put up solar panels and have a roof on which to place them. This comes at a penalty to families that can’t afford solar panels but could benefit greatly from lower electricity rates. While homeowners who have rooftop solar get tax credits on top of cheap electricity, people who rent or live in condominiums pay higher rates.

HECO—which also owns and operates Maui Electric Company, Ltd. (MELCO) and Hawaiian Electric Light Company, Inc. (HELCO)—is hoping to address this by rolling out community-based solar later this year. “We will be able to add over 235 megawatts of solar capacity that will benefit renters, apartment dwellers, and moderate income folks who cannot put solar on their roof because they do not own one,” said HECO spokesperson Peter Rosegg. “They will be able to subscribe to a system on their island and get bill credits for the electricity produced, and participate in the solar revolution.”

Oʻahu’s disadvantage is Kauaʻi’s advantage

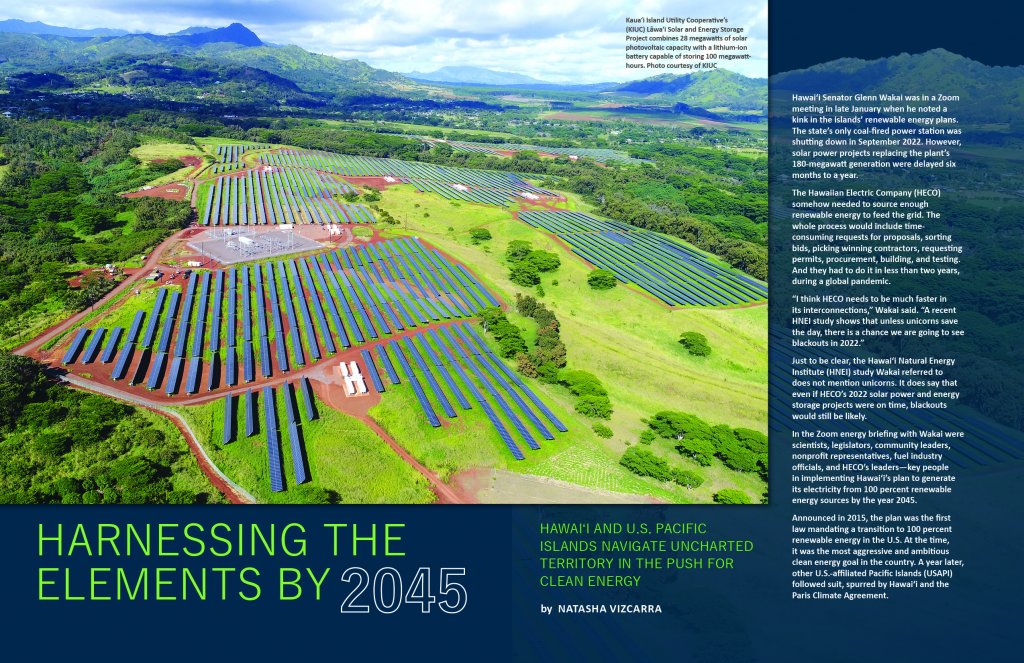

Kauaʻi, on the other hand, has stabilized its electricity rates for residents and found solutions to the island’s limitations. “You really have to look at each island’s characteristics and resources,” said David Bissell, president and chief executive officer of the Kauaʼi Island Utility Cooperative (KIUC). “Even within the Hawaiian Islands, there is no cookie-cutter way to do this.”

From the get-go, KIUC aimed for large utility-scale projects because they had available land. That made utility-scale solar cost effective for Kauaʻi. However, KIUC has been unable to explore other renewables because of the island’s geography. Wind power is not an option because federal protections for endangered seabirds prevent it from being feasible on Kauaʻi. “That takes away a fairly significant, cost-effective renewable option that the other islands have,” Bissell said.

Kauaʻi also does not have geothermal energy like Hawaiʻi Island and won’t pursue new biomass projects. “With biomass, there are concerns about carbon emissions,” Bissell said. “And the technology is expensive because we can only do it small-scale on the island.”

Nevertheless their approach has disentangled their rates from volatile crude oil prices. As of 2020, KIUC’s renewable energy mix was 62.5 percent solar, 17.9 percent hydro, and 19.6 percent biomass—all providing 60 percent of their power generation. KIUC is on track to achieve 70 percent clean energy by 2030. However, an exciting innovation could push the island towards 80 percent—a solar power pumped hydro project.

“That takes a big field of solar panels which generates energy to run pumps. The pumps bring water uphill to a reservoir where it is stored during the day,” Bissell said. “Then the water runs down a pipeline to another reservoir at night, spinning a turbine which in turn creates energy.”

Water in the reservoir acts like a battery. It stores energy during the day and generates energy at night when the island’s solar farms are inactive. The project is part of KIUC’s strategy to find long-duration energy storage, beyond the lithium-ion batteries used today.

Bissell is optimistic that renewables will keep the island’s prices stable for a long time. “And as we change out more projects, that should actually have some decrease in price in the long run,” he said.

A different picture in the USAPI

In Palau, a small archipelago 4,700 miles west of Hawai‘i, Tutii Chilton has also thought about cheaper electricity and who needs it the most. Chilton is the executive director of the Palau Energy Administration and leads the effort to generate 45 percent of the country’s energy from renewable sources by 2025.

“[It may seem strange that] for somebody who works in an energy administration I don’t have a solar system in place,” Chilton said. “But there are people out there who need it more than I do, and I’m fortunate enough to have a position that allows me to pay for the conveniences of everyday life.”

“Renewable energy cannot allow people to slip through the cracks,” he added.

Like others in the USAPI, Palau is dealing with its vulnerability to climate change even as it shakes off dependence on fossil fuels. Chilton has seen the changes in Palau’s shoreline and the high tides that flood lowland taro patches.

Palau’s target is tied to its Nationally Determined Contribution, a set of climate goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions pledged by parties to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Chilton feels his country needs to focus on adaptation, figuring out how to live with the effects of climate change they are already experiencing, instead of mitigation, actions that reduce the risks of climate change.

“We’re sort of caught between a rock and a hard place, trying to be globally responsible citizens,” Chilton said. “Yet the people who actually produce the most emissions are not reducing theirs.” Nevertheless, Palau is committed to meeting its 2025 target, though progress is slow.

As of 2019, the U.S. territories of American Samoa, and Guam; the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; and U.S.-affiliated countries Republic of the Marshall Islands, Republic of Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia have included 1 to 4 percent of solar in their energy mix. The remainder is sourced from fossil fuels, primarily diesel. Solar has been the first renewable choice because it has been the cheapest to start with. Guam leads the pack, with the 26-megawatt Dandan solar farm operating since 2015. More solar companies will provide an additional 120 megawatts by 2022 and another 60 megawatts by 2024. Other islands have had their renewable energy projects slowed or completely stalled by the pandemic.

Some islands need financial support from donor countries to get their programs off the ground. For example, Palau recently received a $3 million grant from the Asian Development Bank to help poor families and women access disaster-resilient clean energy. The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands received financial help from the U.S. Department of the Interior to look into extracting methane gas from landfills, which would help them reduce their reliance on fuel imports.

Not always high-tech and fancy

Like Hawaiʻi, these islands had to figure things out from scratch. Hawaiʻi’s clean energy legislation essentially directed electric companies to implement an increasing percentage of renewable energy sources into their sales until the 100 percent deadline in 2045. This process is happening more tentatively in the island territories.

USAPI nations are also more vulnerable to extreme storms and have had to innovate the way they use solar panels. Elizabeth Doris manages a program at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado that helps islands transition to renewable energy. She has worked with partners in these islands and elsewhere like the Caribbean, where there are strong storms as well.

“Do you want them lower to the ground, or at a lower angle to get out of the wind?” Doris said. “The people who are in that community know which technologies are needed and will be used in the event of a disaster.”

Doris recalls one solution where islanders installed solar panels on a truck that was protected during a storm. Islanders charged the panels and drove the truck around to charge people’s phones. “That makes a huge difference,” Doris said. “It’s not always high-tech and fancy.”

Video game designer and entrepreneur Henk Rogers had that in mind when he designed The Cube, a compact and easily transportable solar power kit that could power a small village. Henk fit solar panels, batteries, an inverter, and charge controllers in an 8-foot shipping container.

“It takes about two hours to set up,” Rogers said “That’s why I think that it’s a good solution for emergency situations.”

The Cube is still in the research and testing stage at Rogers’ Blue Planet Research, an off-grid, energy research lab on his 28-acre ranch in Kona, Hawai‘i. After it is finalized, he intends to ship out Cubes to remote island countries that struggle to provide electricity to isolated villages.

“I was talking to the ambassador of Fiji who said they have islands where children study in schools that have no electricity,” Rogers said. “No electricity means no internet. We are teaching our children how to live in the last century.”

Planning for the homestretch

What would it take for the USAPI to reach their targets? It might mean looking beyond solar power and its affordability to get to the homestretch.

Palau is considering technology that makes sense for the archipelago in the long term. “With solar, you cannot have a 24-hour system without batteries, and this means more equipment and more investment,” Chilton said. His department is planning feasibility studies on ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) and green hydrogen.

OTEC harnesses energy from temperature differences between ocean surface waters and deep ocean waters. The temperature differences power a turbine that produces electricity. It’s ideal for a small island nation like Palau, because in addition to electricity the process also yields desalinated water.

The technology is still expensive, and Chilton realizes OTEC will not come to Palau within the next few years. It would even mean bigger investments, but he thinks the benefits seem the right fit for the country.

Green hydrogen, on the other hand, uses sunlight and special semiconductors to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, with the hydrogen gas then used to produce electricity. The technology is further along commercially than OTEC. Hydrogen fuel cell electric cars already hum along streets in Hawai‘i and worldwide.

“Hydrogen is the next big thing,” said Rogers, who lives off-grid in Kona and makes hydrogen for those long stretches of cloudy days when his solar panels are useless. Rogers—whose Blue Planet Foundation was instrumental in getting Hawai‘i’s legislators to commit to 100 percent clean energy by 2045 in the first place—is developing several hydrogen solutions in his lab.

“We’re not a public-facing organization. We’re just quietly doing things,” he says. “But yes, we are doing a lot of things with hydrogen.”

Senator Wakai echoes Chilton’s and Rogers’ forward thinking, and says the state needs to think beyond solar and land-based wind energy to get to 2045. “Hydrogen and offshore wind are going to be necessary parts of our energy portfolio,” he said.

It looks like it is going to happen. The Hawaiʻi State Energy Office is already investigating the costs and viability of installing offshore wind turbines around Oʻahu, which can harness higher-speed and more consistent wind than their fixed-placed versions on land. They are working with federal agencies to update resource maps and to organize community dialogues.

When Wakai said these would be Hawai‘i’s most difficult years leading to 2045, he was right. But they are unfolding as the state’s most innovative, boundary-pushing, and inventive years, and could serve as a blueprint for other states or the country’s new targets under President Joe Biden. Many of those investing time, money, and energy in this goal believe Hawaiʻi will get to 100 percent clean energy by 2045. With the stakes so high and the motivation strong, Hawaiʻi might just get there sooner than expected.

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE