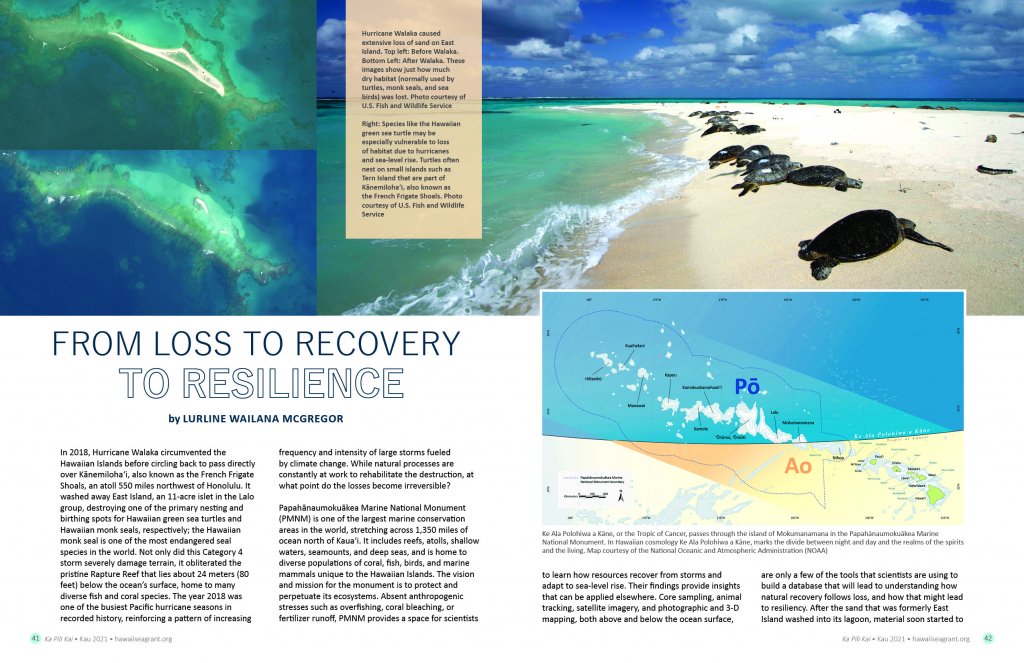

In 2018, Hurricane Walaka circumvented the Hawaiian Islands before circling back to pass directly over Kānemilohaʻi, also known as the French Frigate Shoals, an atoll 550 miles northwest of Honolulu. It washed away East Island, an 11-acre islet in the Lalo group, destroying one of the primary nesting and birthing spots for Hawaiian green sea turtles and Hawaiian monk seals, respectively; the Hawaiian monk seal is one of the most endangered seal species in the world. Not only did this Category 4 storm severely damage terrain, it obliterated the pristine Rapture Reef that lies about 24 meters (80 feet) below the ocean’s surface, home to many diverse fish and coral species. The year 2018 was one of the busiest Pacific hurricane seasons in recorded history, reinforcing a pattern of increasing frequency and intensity of large storms fueled by climate change. While natural processes are constantly at work to rehabilitate the destruction, at what point do the losses become irreversible?

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) is one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world, stretching across 1,350 miles of ocean north of Kauaʻi. It includes reefs, atolls, shallow waters, seamounts, and deep seas, and is home to diverse populations of coral, fish, birds, and marine mammals unique to the Hawaiian Islands. The vision and mission for the monument is to protect and perpetuate its ecosystems. Absent anthropogenic stresses such as overfishing, coral bleaching, or fertilizer runoff, PMNM provides a space for scientists to learn how resources recover from storms and adapt to sea-level rise. Their findings provide insights that can be applied elsewhere. Core sampling, animal tracking, satellite imagery, and photographic and 3-D mapping, both above and below the ocean surface, are only a few of the tools that scientists are using to build a database that will lead to understanding how natural recovery follows loss, and how that might lead to resiliency. After the sand that was formerly East Island washed into its lagoon, material soon started to migrate back onto its reef platform. Within one year, satellite images showed that the island was almost half restored.

East Island, in particular, has played a pivotal role in the life cycles of several important species. From tracking device data, scientists know that over 90 percent of all Hawaiian green sea turtles travel to East Island to lay eggs, and they have started returning since Walaka struck. Yet, because the turtles don’t nest every year, the impact of Walaka on their population may not be fully known for another 20 years, as turtles don’t reach sexual maturity until age 25.

Hawaiian monk seals require beaches for giving birth and nursing their pups. For decades, the small sand islands of the French Frigate Shoals used by monk seals have been shrinking. Notably, three of the four largest islands in the atoll have either substantially or entirely disappeared. This habitat loss has been linked to impaired survival of young monk seal pups for a variety of reasons, including drowning and shark attacks.

“Mitigating the threats associated with terrestrial habitat loss has mostly been on an individual seal by seal basis, such as relocating weaned pups to Tern Island, the largest islet at French Frigate Shoals, where they will be safer,” says Dr. Jason Baker, a protected species division marine biologist with the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. “People are discussing how to, perhaps, engineer resilience in the islands, but that will be very complicated.” Meanwhile, scientists are monitoring the changes to see how the loss of habitat at French Frigate Shoals will impact the potential for sea turtles and monk seals to recover.

“If you have a big storm every ten years, the resource will come back partially, then get knocked down again,” says Dr. Randy Kosaki, PMNM deputy superintendent. “There will come a point where it canʻt recover fast enough. There isn’t much we can do locally as managers. It really comes back to using disastrous events to raise awareness and change behavior internationally as our best hope to stave off the impacts of climate change. From a scientific perspective, the best thing we can do is watch, monitor, and collect data on the decline, and hopefully in my lifetime, we will see it showing an improvement. I expect to see the coral at Rapture Reef come back before I retire.”

In Hawaiian cosmology, Ke Ala Polohiwa a Kāne, or the Tropic of Cancer, marks the divide between the world of ao, the light and the living, and pō, darkness, the sacred realm of gods and spirits, which lies north of the boundary. Kalani Quiocho, PMNM Native Hawaiian program specialist, explains how the natural resources protected in PMNM, much of which lies above the Tropic of Cancer, are a part of the collective cultural heritage of Hawaiʻi and humanity. “They represent our values, our knowledge, our identities, and all of the inspirations and things that motivate us. The more we lose these natural resources, the more we are at risk of losing our culture. As we lose the islands, we potentially lose that source of knowledge and identity which is closely related to place. But if we are resilient enough, then we will adapt, perpetuate, and continue to be.”

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE