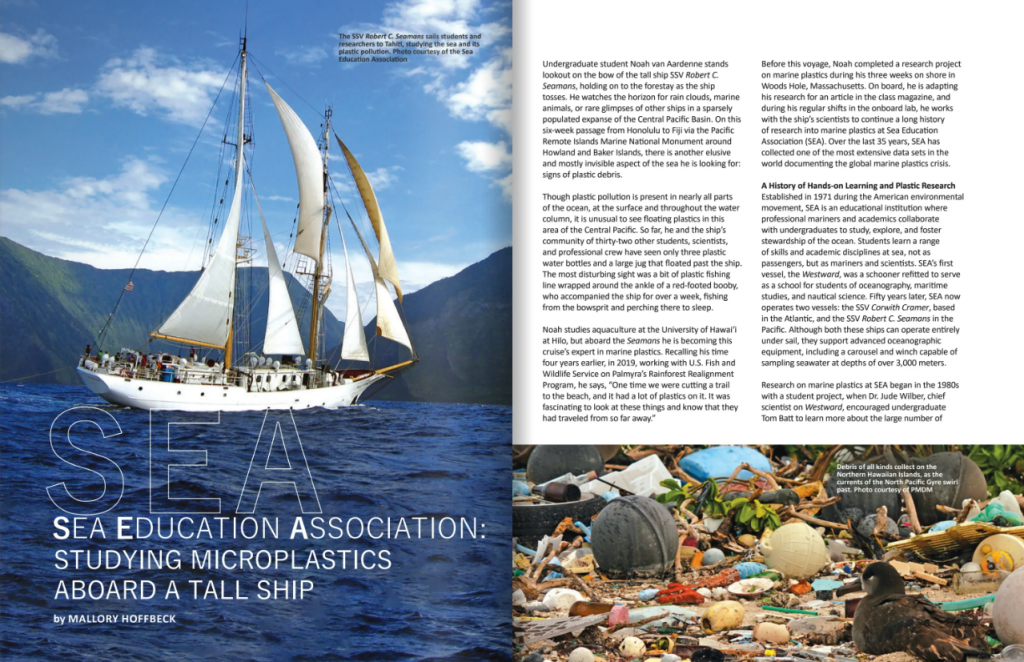

Undergraduate student Noah van Aardenne stands lookout on the bow of the tall ship SSV Robert C. Seamans, holding on to the forestay as the ship tosses. He watches the horizon for rain clouds, marine animals, or rare glimpses of other ships in a sparsely populated expanse of the Central Pacific Basin. On this six-week passage from Honolulu to Fiji via the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument around Howland and Baker Islands, there is another elusive and mostly invisible aspect of the sea he is looking for: signs of plastic debris.

Though plastic pollution is present in nearly all parts of the ocean, at the surface and throughout the water column, it is unusual to see floating plastics in this area of the Central Pacific. So far, he and the ship’s community of thirty-two other students, scientists, and professional crew have seen only three plastic water bottles and a large jug that floated past the ship. The most disturbing sight was a bit of plastic fishing line wrapped around the ankle of a red-footed booby, who accompanied the ship for over a week, fishing from the bowsprit and perching there to sleep.

Noah studies aquaculture at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, but aboard the Seamans he is becoming this cruise’s expert in marine plastics. Recalling his time four years earlier, in 2019, working with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Palmyra’s Rainforest Realignment Program, he says, “One time we were cutting a trail to the beach, and it had a lot of plastics on it. It was fascinating to look at these things and know that they had traveled from so far away.”

Before this voyage, Noah completed a research project on marine plastics during his three weeks on shore in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. On board, he is adapting his research for an article in the class magazine, and during his regular shifts in the onboard lab, he works with the ship’s scientists to continue a long history of research into marine plastics at Sea Education Association (SEA). Over the last 35 years, SEA has collected one of the most extensive data sets in the world documenting the global marine plastics crisis.

A History of Hands-on Learning and Plastic Research

Established in 1971 during the American environmental movement, SEA is an educational institution where professional mariners and academics collaborate with undergraduates to study, explore, and foster stewardship of the ocean. Students learn a range of skills and academic disciplines at sea, not as passengers, but as mariners and scientists. SEA’s first vessel, the Westward, was a schooner refitted to serve as a school for students of oceanography, maritime studies, and nautical science. Fifty years later, SEA now operates two vessels: the SSV Corwith Cramer, based in the Atlantic, and the SSV Robert C. Seamans in the Pacific. Although both these ships can operate entirely under sail, they support advanced oceanographic equipment, including a carousel and winch capable of sampling seawater at depths of over 3,000 meters.

Research on marine plastics at SEA began in the 1980s with a student project, when Dr. Jude Wilber, chief scientist on Westward, encouraged undergraduate Tom Batt to learn more about the large number of plastic pieces they found in their net tows. Scientists had noticed the presence of plastic pieces in the ocean by 1960, noted by the first published study to report ingestion of plastic pieces by seabirds. Early studies on the issue continued throughout the 1970s, notably by SEA’s next-door neighbor, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. In 1987 Dr. Wilber published students’ findings from 1984–1987 on high concentrations of marine plastics they found in the Sargasso Sea. It has since been a standard activity on SEA cruises to record data on plastic pieces collected in net tows.

Current research at SEA is led by Dr. Kara Lavender Law, a professor of oceanography and now an international expert on marine plastics who has authored several global studies on the issue. For the past 16 years, she has led SEA’s plastics research program, analyzing the dataset to which Noah is contributing. SEA will soon post a global dataset in a downloadable portal on its Plastics Lab website, where anyone can freely access SEA’s decades of marine plastics data for scientific research or individual learning.

Plastics Research in 2023

Originally from Southern California, Noah saw the Seamans docked in San Diego while he was visiting home in 2022. The crew was preparing for another long voyage at sea. He was curious enough to approach the ship and chat with them. “They were provisioning the ship,” Noah says, “loading it up with fruit. I found out it was a student program that was focused on research, and you learn how to sail.” He sent in an application. “It’s so cool that back in October I saw the ship,” he adds. “And here I am, living on it for six weeks.” Now Noah stands watch in shifts and contributes to all the tasks of a typical deckhand, while also going to class, deploying the scientific equipment, and processing samples.

As they travel through the Central Pacific in the summer of 2023, Noah and his shipmates are always watching for visible plastics floating in the water, but their research focuses instead on the tiny pieces caught in net tows and examined under the microscope. When weather conditions allow, twice each day the students and scientists deploy a long, narrow net towed alongside the ship, sampling the surface layer of the ocean. This neuston tow was originally designed to capture zooplankton, but it also collects marine debris as it moves through the water. The students haul the net back on board and help to record its contents, identifying plankton species and storing visible plastic pieces in vials that are sent back to SEA’s lab in Woods Hole for analysis. Some of the students aboard the Seamans are surprised that they have not encountered more plastic debris along this particular cruise track, since they have often heard about plastic abundance in the ocean.

This rarity is almost certainly because the cruise track passes through an area with currents that carry debris away to other parts of the ocean. In 2022, a previous SEA voyage from Hawaiʻi to California visited the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, where currents amass a particularly large amount of debris, mostly in the form of tiny microplastics. This is the area famously known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” On that passage, the students regularly reported dozens to hundreds of plastic pieces in their daily neuston tows, one day counting as many as 1200 individual pieces. But while currents concentrate debris in that area of the Northeast Pacific, they carry it away from where the Seamans sails on this 2023 voyage. So in striking contrast, Noah and his shipmates counted just 11 pieces in their first three weeks at sea.

One morning near the end of the program, Noah finishes his watch and climbs down from the bow. “This voyage has been an introduction to sailing, oceanography, and marine research. If I get a job in any of these fields, I already have hands-on experience,” he says, reflecting on his time at SEA. “Not a lot of undergrads get the chance to go out and do hydrocasts and neuston tows, or to live and work with their professors and maintain a ship at all hours of the day and night. And it’s great if my research gets to be part of something bigger, that people at SEA have been working on for a long time.”

For more information about SEA’s Plastics Lab, visit: https://sea.edu/academics-and-research/sea-plastics-lab

Browse Ka Pili Kai issues HERE